An Internationalist Vision of Black History Month

Black History Month has always had an international outlook. From its origins as Negro History Week, started in 1926 by the historian Carter G. Woodson, the goal has been two-fold: to celebrate the intellectual, political and cultural contributions of prominent Black figures, and to teach the history of the lives and experiences of people of African-descent. This project was necessarily international. As Woodson’s accounts of early celebrations in the Journal of Negro History show, the week’s events focused on both the United States and the African continent.

In subsequent decades, Negro History Week became even more international in its scope. Its commemoration included the sale of pamphlets that featured profiles of prominent Black figures to be used for educational purposes in schools and community organizations. The politicians and thinkers who were featured in the 1951 Negro History Week Kit for example, came from many different countries throughout the African diaspora including Brazil, Nigeria, Ethiopia, and French Guyana. The goal of this international lineup was to “emphasize the struggles of Negroes at home and abroad to achieve first class citizenship.”1

The internationalist vision of Black History Month is therefore important because it connects Black struggles in the United States to movements for liberation worldwide. It both recognizes the particularities of the United States context and emphasizes the need for global solidarity as the most effective response to the global nature of imperialism and white supremacy. This year’s celebration of Black History Month provides an occasion to reflect on some of the thinkers and activists who have been featured in Negro History Week Kits, pioneers of Black internationalism whose work reflected the expansive geographic scope of Black intellectual production and political work.

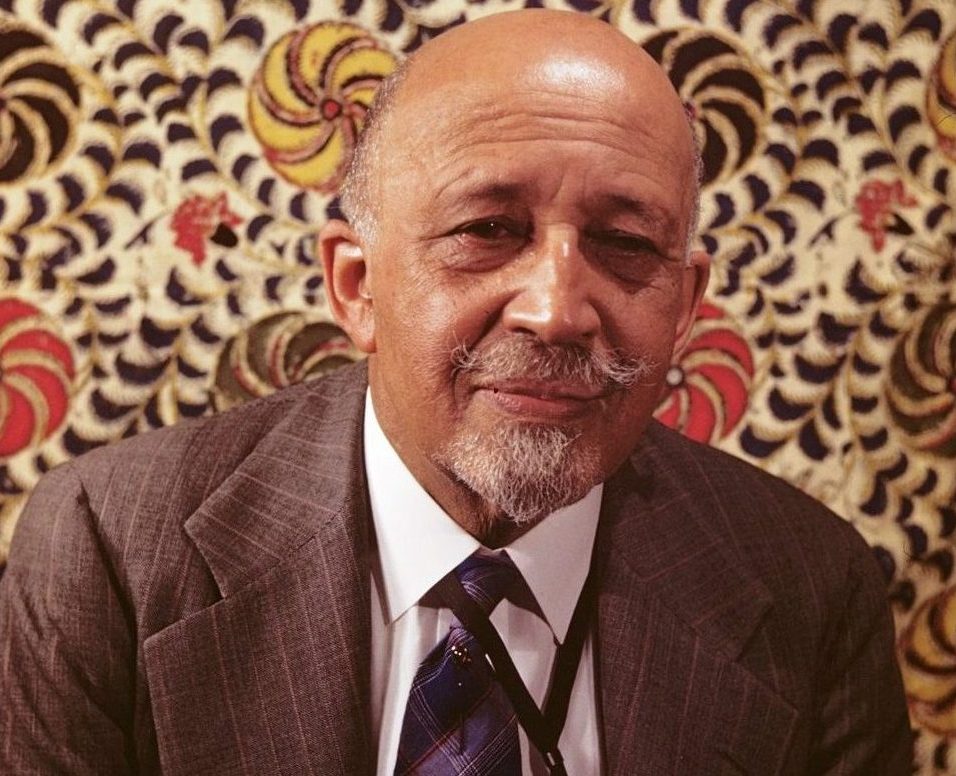

W.E.B. Du Bois

W.E.B. Du Bois remains a major figure in African American history and there is extensive research on the importance of his work at home and abroad. He spent the last years of his life in Ghana at the invitation of Kwame Nkrumah where he worked on an Encyclopedia Africana, a project that testifies to his enduring commitment to advancing knowledge about the cultures and civilizations of people of African descent throughout the African diaspora. In many ways, Du Bois’ time in Ghana was the culmination of the internationalist vision that characterized his life’s work. Indeed, Du Bois’ astute and lucid analyses of racism in the United States went hand in hand with his reflections on global white supremacy. He expressed his belief in global solidarity as a response to imperialism on numerous occasions, including at the second Pan-African Congress which met in London, Brussels and Paris in 1921. The Congress drew participants from West and Central Africa, the Caribbean, the United States and the United Kingdom who came together to discuss the on-going colonial domination to which their countries and territories were subjected, and to propose solutions.

After the Congress, Du Bois presented a manifesto to the League of Nations that highlighted a collective commitment to the eradication of colonialism worldwide. The manifesto specifically targeted two interconnected areas that contemporary scholars now identify as constituting the coloniality of power. The first was a labor hierarchy that placed people of African descent on the receiving end of exploitation. The second was a racial hierarchy in which Black people were again in the unfavorable position of being viewed as inferior or lacking civilization. Du Bois sought to counter these two manifestations of inequality by appealing “most earnestly and emphatically to ask the good offices and careful attention of the League of Nations to the condition of civilized persons of Negro descent throughout the world.” He suggested that colonialism was not tenable indefinitely because “the spirit of the modern world moves toward self-government as the ultimate aim of all men and nations.” Forty years later, Du Bois’ Encyclopedia Africana project in Ghana would aim to provide a direct response to the supposed absence of Black civilizations by highlighting the contributions of people of African descent to cultural and intellectual production on a global scale. Indeed, the vision of racial solidarity and international cooperation that characterized Du Bois’ interventions at the Pan-African Congress and subsequent meetings, ran through much of his work as he dedicated his life to the pursuit of justice and equality for Black people throughout the African diaspora.

Dantès Bellegarde

Dantès Bellegarde had just begun his career as an international diplomat when Du Bois invited him to take on the role of honorary President of the 1921 Pan-African Congress. The Haitian politician was born in Port-au-Prince in May 1877 and worked in the political milieu in his home country until his appointment to the League of Nations in 1921. He used his position in this international body to criticize global manifestations of imperialism and white supremacy. For example, he was a critic of the American occupation of Haiti and later criticized the United States’ imperial designs on Latin America and the Caribbean. He also denounced the South African government’s massacre of indigenous people over a land dispute. The geographic reach of Bellegarde’s political work included the United States. Du Bois attested to this connection when he wrote to Bellegarde, “I want to let the colored people of the United States know how splendidly you have represented them as well as Haiti.”2 Bellegarde’s critique of imperial power sometimes came at a professional cost, and his correspondence with Howard University professor Alain Locke establishes a connection between his racial politics and the loss of his position as Haiti’s ambassador to the United States.

As a member of the French-speaking elite in Haiti, Bellegarde’s work and subsequent legacy is marked by a certain ambivalence between his critiques of American imperialism and his investment in political structures that maintained ties to the United States and France. Like Du Bois, Bellegarde’s writings position questions of imperialism on both a local and international scale. His collection of essays, Dessalines Has Spoken, for example, contains reflections on a variety of subjects including Haitian-American relations and Haitian national identity through what Bellegarde describes as the Dessalinian tradition of using the term “noir” instead of the more pejorative “nègre.” The scope of his reflections squarely places him in the pantheon of Negro History Week Kit figures whose work spanned both “home and abroad.”

Jane Vialle

Negro History Week Kits featured very few women. Jane Vialle was one of the few in addition to Sojourner Truth and Phyllis Wheatley. Vialle’s contributions to Black internationalism came in the form of her political work and activism in France, Central Africa and the United States. She saw the struggles for racial equality in each of these locations as different yet related. In 1951, she gave a talk at Hunter College where she argued that “women and education are the potential sources for the development of democracy in Africa.”3 In this speech, delivered in the United States in a class on European history, Vialle reclaimed space for a conversation about centering the roles that African women would play in the move from colonialism to democracy. In addition to physical travel, Vialle also founded a women’s association and a journal whose international circulation allowed her to create a large network of women in the French empire who were committed to denouncing racism and working towards gender equality. Her demands for equal citizenship for the African constituents she represented in the French Senate earned her a spot in the 1951 Negro History Week Kit’s lineup of Black figures who had made important political and intellectual contributions in the African diaspora.

These three figures were only a few of the many Black thinkers whose work has been recognized and celebrated during Black History month. Their commitment to an internationalist vision of cooperation, solidarity and anti-imperial action dovetails with local struggles in the United States and highlights the continued international outlook of Black History month.

Timely …