Black History Month, A Reflection and Defense

As Black History month was approaching, I began to ponder the meaning of this occasion in our modern world. My work at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture made me wonder if certain conversations on the significance of African American history that were held in previous generations were truly needed in academic settings today. I thought the answer was no, until I read The Historians Manifesto by Jo Guldi and David Armitage.

The Historians Manifesto was published as an open access book in October 2014 by Cambridge University Press. The authors’ assertion is that the work is a treatise on how the field of history must proceed in the modern digital age. In order to combat the trend of instant gratification in today’s society and the emphasis of short term history, they emphasize a return to longue durée. Longue durée was a term coined by French historian Fernand Braudel in 1958. The term as interpreted by Guldi and Armitage implies the use of big data sets and a wider chronological perspective like emphasizing trends and themes over several hundred years over several decades. Longue durée is in direct contrast to micro- history which evolved in the 1970s. Micro history focused on shorter time frames and concentrated on “exceptional individuals, seemingly inexplicable events, or significant conjunctures.”[1] While not stated covertly, the work’s assertion is that micro-history evolved out of a need to create a safe writing zone for scholars’ political commitments and radical causes, especially in the case of the Civil rights movement, anti-war protest, and feminism. The unintended consequence of micro-history was that it was writing for communities just finding their political voices, and it furthered the movement toward greater specialization within academia. The juxtaposition of longue durée with micro-history is meant to bolster the author’s claims of the importance of long term historical perspective, but in the case of unintended consequences it is an assertion of the insignificance of minority history.[2] This inference is problematic as well as the assertion that minorities and women, did not “find their voice” until the 1970s.

The African American community had a very strong voice by the 1970s which reverberated throughout the rest of the twentieth century. The voice that Guldi and Armitage are acknowledging in terms of the production of scholarly books and articles had achieved a new level of momentum by the 1970s and was influence by the contemporary sociopolitical atmosphere.

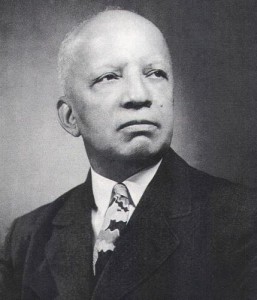

In the case of Black History Month, its antecedent was started in the 1920s by Carter G. Woodson, and evolved in the midst of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. Carter G. Woodson earned his graduate degrees at the University of Chicago and Harvard University. In 1915 he formed the Association of Negro Life and History to preserve, promote, and interpret African American history to the global community.[3] In 1916, he would establish The Journal of Negro History, later The Journal of African American History, a refereed journal. This journal offered African American scholars an opportunity to publish articles when denied publication in other major historical journals. He continued his quest to make Black history widely available by urging African American civic organizations to highlight African American achievements and history. In 1924, the historically black fraternity Omega Psi Phi started Negro History & Literature Week, and in 1926 ASNLH formed Negro History Week. Negro History Week was traditionally held during the week celebrating the birthdays of two figures significant to African American history, Abraham Lincoln on February 12 and Frederick Douglass on February 14. There was a tradition of celebration of Lincoln’s birthday since his assassination in 1865 within the African American community. A similar celebration existed for Frederick Douglass since his death in 1895. Woodson’s intention was for Negro History Week to be a temporary occurrence. His hope was that African American history would then be integrated into the curriculum for both children and adults. Woodson died in 1950 as the modern United States Civil Rights movement was gaining momentum. By the 1960s the cultural sentiment especially on college campuses led to extension of Negro history week to Black history month. Black history month is part of Woodson’s public legacy. Academically, he fostered the careers of several historians like John Hope Franklin who influenced major trends in translating our concept of the American history narrative and Rayford Logan who was a part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s Black cabinet.[4]

Scholars of European history may regard African American history as micro-history, but the work of Woodson and others has been more than highlighting the achievements of notable individuals. Woodson demonstrated that African Americans have been significant participants and contributors of the American historical narrative. It is important to note that some of the early African American scholars encountered legitimate challenges in their research. Segregation laws throughout much of the United States, hindered access to resources. By the time the south is desegregated in the 1970s, the research resource paradigm has changed and so does the level of scholarly production.

For us here at the African American Intellectual History Society, we are several generations removed from Woodson’s immediate contributions. Yet we engage in a new level of conversation on African American history like the intellectual contributions of noted individuals like Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. DuBois and others. We embrace and counter the mainstream paradigms of interpretation while placing African Americans significantly within it. We are continuing Woodson’s legacy. The ignorance of others of the depth of this history and its work can in no way diminish its value and relevance in the micro and macro conversations of history.

[1] Guldi, Jo and David Armitage. The Historians Manifesto (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014),11.

[2] I will detail other aspects of their argument in later blog posts.

[3] Association for African American Life and History, “ASALH Mission” accessed February 1, 2015 http://asalh100.org/mission/.

[4] Daryl Michael Scott, “Origins of Black History Month,” Association for African American Life and History, accessed February 1, 2015 http://asalh100.org/origins-of-black-history-month/.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

This is a fantastic post, Dr. Trent.

I’m especially drawn to your suggestion to think of the “public” legacy of Woodson, et. al., as “more than highlighting the achievements of notable individuals” but rather a clear demonstration “that African Americans have been significant participants and contributors of the American historical narrative.” In addition, to me your suggestion also constitutes important thinking about the role of commemoration and historical memory in assessing that legacy.

I’ve recently been (re)reading through aspects of black history month’s history via Pero Dagbovie’s work, as well as the annual reports Woodson published in the JNH and W. E. B. Du Bois’s numerous lectures, presentations, and newspaper columns on the subject. With the 90th anniversary of Negro History Week/Black History Month just around the corner, black history in the most expansive sense of the term (whether in the form of micro or macro history) is as vital as ever, 24/7/365. You’ve given us much to consider. Thank you.