Ghana, France, and the Re-writing of Colonial Narratives

Emmanuel Macron’s recent tour of Africa followed the well-worn path of French presidents visiting former colonies. In the past, this tradition took his predecessors on a circuit of African countries, each stop punctuated with a revisionist speech that subsequently sparked heated debate about the enduring legacy of French colonialism. Last week, Macron sought to separate himself from this tradition in the same way he worked to present himself to the French electorate as a new alternative to the establishment, using his preferred strategy of highlighting his age. Turning to social media while in Burkina Faso, Macron reminded his followers that his relative youth put him at a temporal remove from colonialism. Colonialism was old news. As a fresh young face on the scene, this French presidential tour of Africa would be different. It would break the mold. From Emmanuel Macron’s Facebook on Nov. 28th, 2017:

I’m from a generation that has never known colonial Africa. I am from a generation that one of the most beautiful political memories is Nelson Mandela’s victory over apartheid. That’s the victory of our generation.

Beyond his engagement with French-speaking Africa, Macron’s stop in Ghana, a former British colony, has been interpreted by some as a calculated move to take advantage of the inward focus of a post-Brexit United Kingdom to expand French economic influence in the face of Chinese presence in Africa. If anything broke the mold on Macron’s trip, it was his time in Ghana. This is not so much because it was the only country on the itinerary that was not a former French colony, but because the Ghanaian president’s speech in a joint press conference with Macron immediately went viral. In his response to a journalist’s question about whether France would provide financial support beyond its former colonies, Nana Akufo-Addo asserted: “We have to get away from this mindset of dependency. This mindset about ‘what can France do for us?’ France will do whatever it wants to do for its own sake, and when those coincide with ours, ‘tant mieux’ as the French people say…Our concern should be what do we need to do in this 21st century to move Africa away from being cap in hand and begging for aid, for charity, for handouts. The African continent when you look at its resources, should be giving monies to other places…We need to have a mindset that says we can do it…and once we have that mindset we’ll see there’s a liberating factor for ourselves.”

Akufo-Addo’s remarks have been hailed as a bold call “for Africa to end its dependency on the West,” a “surprise [to] Macron with a clear rejection of development aid,” and even as “schooling” the French president. Indeed the Ghanaian president himself took the stance of one courageously speaking truth to power by prefacing his remarks with the caveat, “I hope that the comments I am about to make will not offend the questioner too much and some people around here.” Akufo-Addo’s words are indeed worth analyzing. However, rather than dismiss the praise for his speech by Ghanaian outlets with claims about “the lack of understanding of the workings of capitalism and the theory and practice of resistance to neo-imperialism [by] social media users,” it is helpful to apply a historical lens to assessing the implications of the exchange between the presidents of Ghana and France.

In the same way Macron ultimately failed to break his predecessors’ tradition of giving condescending speeches during his Africa tour, Akufo-Addo’s speech was a repetition of another ritual, one that also has roots in colonialist representations. It scolded a vast and diverse continent by oversimplifying the causes of poverty in Africa as the result of a mindset, a failure of African minds to imagine anything beyond dependency on foreign aid. Reversing Africa’s economic misfortunes then becomes but a question of changing a mindset: “We need to have a mindset that says we can do it…and once we have that mindset we’ll see there’s a liberating factor for ourselves.” This reductive narrative, in which economic hardship is cast as a moral failing, echoes the United States’ “bootstraps” ideal that continues to be wielded as an excuse for the American State to avoid providing crucial services and protections for its citizens. It has several dangers in Africa as well. First, it offers very little by way of innovative solutions because it flattens the complex causes of Africa’s economic problems. It also erases the tireless work of entrepreneurs, activists, and artists across the continent who continue to imagine and work towards actual liberation and economic autonomy. Finally, it reinforces the unequal terms on which Franco-Ghanaian relations are structured because it absolves France, and by extension Europe, of the enduring legacy of foreign policies that have largely contributed to the existing situation. In short, Akufo-Addo did not “school” Macron. His finger wagging at Africans because they have not yet acquired a suitably “can do” mindset, played right into Macron’s goal of the post-colonial amnesia he expressed in his Facebook post. Akufo-Addo’s narrative is one that facilitates France’s gleeful forgetting of a past for which it does not want to be held accountable.

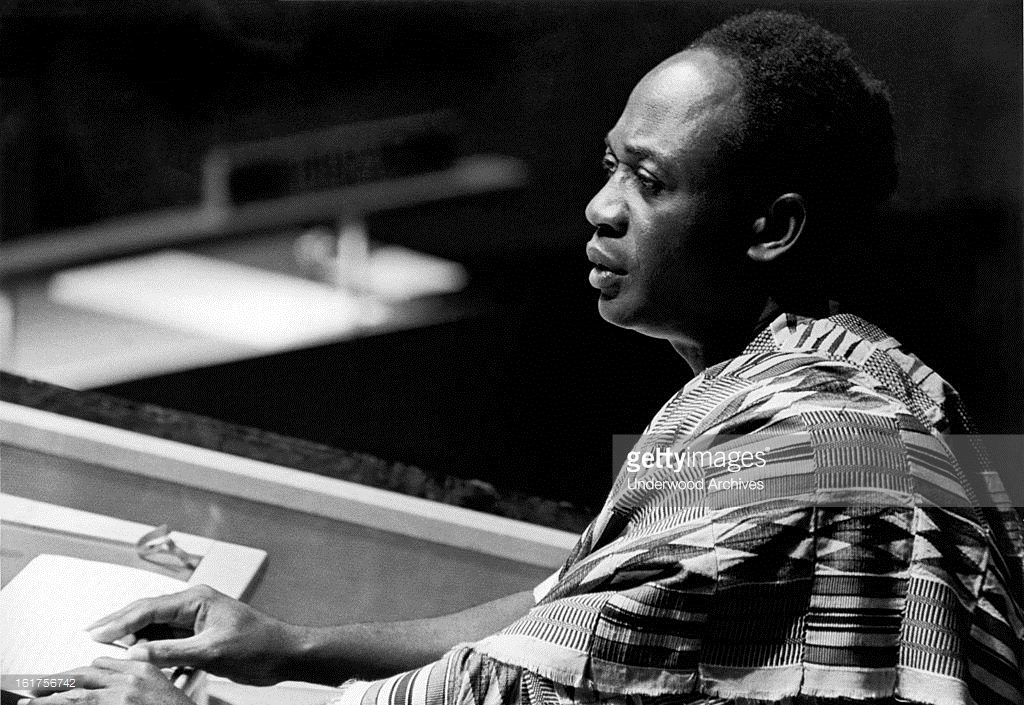

Taking a historical perspective by juxtaposing Akufo-Addo’s words with those of Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, provides an alternative to this “bootstraps” narrative masquerading as a call for African economic liberation. To be clear, I do not turn to Nkrumah out of a sense of nostalgia that would seek to make him an eternal spokesperson for all things political in Ghana and Africa. Rather I do so because in some ways, Akufo-Addo’s words bear similarities to the language that Nkrumah used in defining neo-colonialism. Notably, his recognition that France will always act in its self-interest, echoes similar claims made by Nkrumah in his book Africa Must Unite. Nkrumah however went further to recognize that French interests would also be in conflict with African interests: “Since France sees her continued growth and development in the maintenance of the present neo-colonialist relationship with the less developed nations within her orbit, this can only mean the widening of the gap between herself and them. If the gap is ever to be narrowed, not to say closed, it can only be done by a complete break with the present patron-client relationship.” For Nkrumah, there was no “tant mieux,” no toeing the line between critiquing French aid while mollifying a French leader with caveats that if France decided to provide aid it would be accepted with gratitude.

Certainly, Nkrumah understood what he called “the impossible position” of asserting African agency even when African countries were “strongly dependent on foreign contributions simply to maintain the machinery of their governments.” The radical nature of his stance comes precisely from this recognition of the potential costs of his position, and the belief that the economic costs of a position viewed unfavorably by foreign powers could not outweigh the importance of the task at hand. For Nkrumah, that task was redefining the terms of Africa’s political and economic relations with Europe. Africa Must Unite provides a clear blueprint: “The forward solution is for the African states to stand together politically, to have a united foreign policy, a common defence plan, and a fully integrated economic programme for the development of the whole continent.” This proposed solution was not without its challenges when Nkrumah wrote these words in 1963, and they are not without challenges now.

Akufo-Addo’s desire to shift the terms of Ghana’s foreign relations with wealthy Western countries away from aid is an important first step. However, making the shift towards narrowly locating liberation in the need to change African mindsets is a missed opportunity. Nkrumah’s pertinent words show that history continues to offer up useful lessons on what it would take to truly break the mold of foreign relations predicated on unequal and exploitative terms. As Nkrumah wrote, “only then can the dangers of neo-colonialism and its handmaiden of balkanization be overcome.”

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.