Reading the Language of Violence in the Middle Passage

This post is part of our online roundtable on Sowande’ Mustakeem’s Slavery at Sea

“The dead are not remembered in the cycle of slavery’s horrors” ~Sowande’ M. Mustakeem

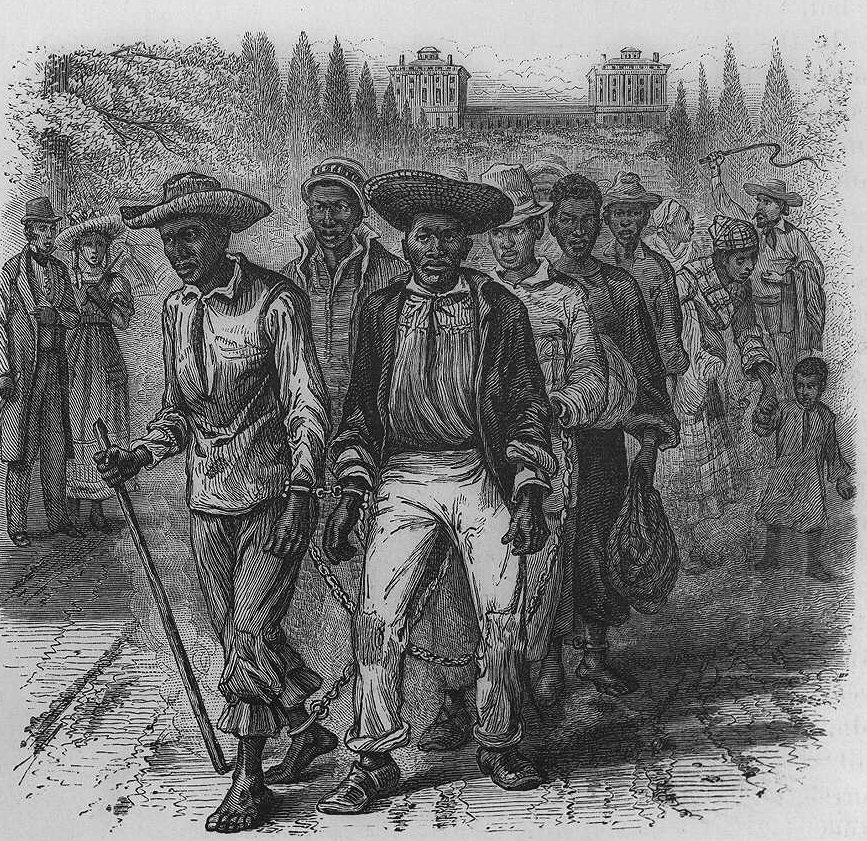

Sowande’ M. Mustakeem’s, Slavery at Sea: Terror, Sex, and Sickness in the Middle Passage, presents readers with a compelling alternate view of the Middle Passage. Mustakeem interrogates the Middle Passage, not solely as a slave-making site, but as a site where Europeans, Africans, and Atlantic Creoles made the dead and where the dead made themselves. The price for doing the business of enslaving millions of Africans who endured the multistage passage from the continent of Africa to plantations in the “New” World was paid in African lives. Of course, those losses shaped the lives of those who survived to confront new horrors on the other side of the Atlantic. But Mustakeem’s intervention comes when she pushes her readers to confront the legacy of the dead. In Slavery at Sea, their maimed, scared, lacerated, and decomposing bodies do not slip away into the ocean. They are the source material for Mustakeem’s study as she shifts her focus away from the journeys of the living and to the sojourns of the dead, disinterring their remains in hopes of asking those who did not survive the Middle Passage what their suffering and their deaths might reveal to us.

Mustakeem asserts that, “Violence operated as a shared language” between captive and captor (p. 77). Sailors, ships’ captains, merchants, the managers of West Africa’s barracoons and their counterparts across the Atlantic endeavored to manufacture slaves. They employed a range of violent acts and practices to communicate with their human property at every step in the long voyage to sale in the “New” World. The enslaved, she notes, spoke back through violence towards their enslavers. They also spoke out through violent acts perpetrated towards themselves. Framing violence as a conversation, the author notes that sailors in particular were acutely aware of the potential for violence shipboard and the dire consequences they could face if a slave ship’s crew could not maintain order. Mustakeem acknowledges the occurrence of shipboard rebellion and asserts that shipboard revolt was not the only form of violent communication enslaved people utilized. She asks the reader to extend and expand the definition of shipboard resistance beyond the more legible instances of revolt on record.

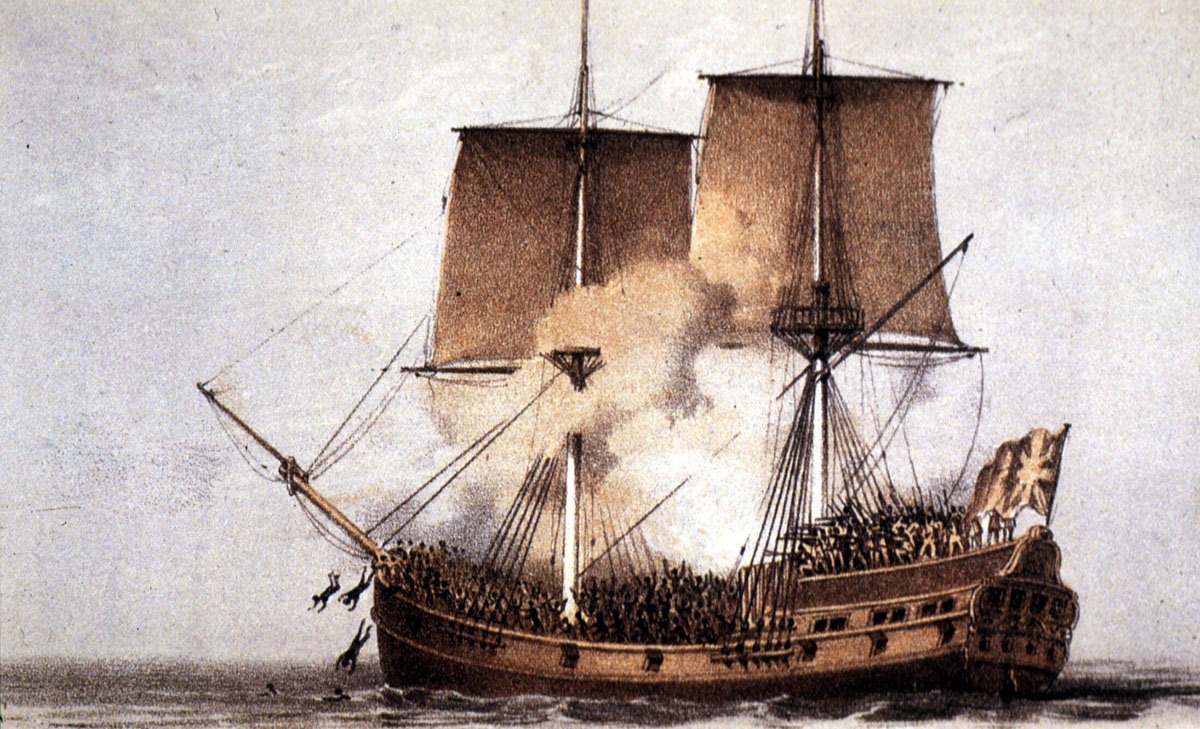

In Slavery at Sea’s fourth chapter, “Blood Memories,” Mustakeem directly juxtaposes slave revolt and the less attended to acts of violence that the enslaved used while shipboard to communicate with their captors. As the author notes, the Unity, a ship from Liverpool, England, had a revolt-plagued voyage in 1769. Amid the chaos of one uprising by the ship’s enslaved cargo, an enslaved man jumped overboard and drowned (p. 97). With this example she subtly makes a point that she more forcefully makes over the course of Slavery at Sea’s fourth and fifth chapters: the spectrum of violent actions used to communicate onboard slave ships often manifested at once, simultaneously, and in sharp relief.

Slavery at Sea’s discussion of self-harm exposes another dimension of the language of violence. Of suicide she writes, “Fleeing ships and creating a spectacle of escape within the open waters, slaves forced crewmen to bear witness to and grapple with the gravity of their cargo losses” (p. 127). This “spectacle of escape,” Mustakeem argues, also links the language of violence the enslaved spoke while shipboard to the language of violence the enslaved spoke on dry land. Like truants, runaways, and maroons, she argues, these “maritime fugitives” asserted control over their own bodies and fled. The author appropriates the term “maritime fugitives,” which has been used to speak about those enslaved persons who escaped bondage by fleeing into the vast community of Atlantic world mariners and the maritime trades. In doing so she casts suicide as an act of definitive agency and not as an act of desperation (p. 127).

In chapter five, “Battered Bodies, Enfeebled Minds,” Mustakeem analyzes the ways in which ships’ crews characterized the mental and emotional health of captives, enslaved people’s cultural responses to sorrow, and practices of self-harm among the enslaved. In so doing, Mustakeem incorporates both cultural expressions and self-harm into a lexicon of violent resistance in very compelling ways. Mustakeem’s use of surgeons’ notes about the “madness” of the enslaved, their responses to separation from their loved ones and home countries, and their shifts in behavior over the course of voyages on the Atlantic, allows her readers a window into the ways crews, captains, and merchants interpreted their cargo’s anguish. The slavers, who appear in Slavery at Sea, were perplexed and vexed by the reality that their human cargo had emotional lives. Their exasperation manifested in brutality and callous negligence. Her analysis also considers what the enslaved intended to communicate to their captors by expressing anguish. The enslaved regularly used violence to force their captors to grapple not just with the loss of cargo but also with their cargo’s losses.

Mustakeem is most effective at discussing violence as a language between slavers and the enslaved. Her incorporation of an analysis of the mental, emotional, and spiritual dimensions of the language of violence spoken by both enslaved people and their shipboard masters is particularly useful and important when investigating the deep lexicon of violent and resistive action used by the enslaved on the African continent, shipboard, and in the “New” World. At the same time, Mustkateem implicitly engages the ways that violence and its physical consequences remains a language that both the reader and the researcher can read and understand. The dead speak.

This is pioneering historical inquiry on Mustakeem’s part. And like all good projects, hers inspires other questions about how treating violence as a language help us understand the Middle Passage. For example: what did the enslaved communicate to each other through the language of violence? In what ways did their solo and collective acts of violence register as a way to communicate with and to each other? True, some voyages held human cargo that spoke the same language, spoke similar dialects, or could piece out some of each other’s languages over the course of the voyage. But amid the pestilence, brutality, mental and emotional anguish, and deprivation of the Middle Passage, it follows that the enslaved also spoke violence to each other and read each other’s violence.

For example, Mustakeem interprets the violence of women who aborted the fetuses they carried as a means to deprive their owners of valuable property and an assertion of control over their own bodies. She notes that their captors sent a message back by meting out physical consequences for their actions or neglecting them as they suffered the physical consequences of an attempted abortion on the high seas. Yet, as Mustakeem notes in earlier chapters, slavers often saw infants, toddlers, and children as liabilities and less valuable cargo. She also notes the violence that enslaved women could not protect their children from at the hands of their captors. In the context of such disregard for the lives of captive children, perhaps the message enslaved women intended to send to ships’ crews was not the same as those sent to plantation owners, who in some contexts regarded children as dividends paid on their initial investment. When a woman made the decision to attempt an abortion, surgically or through herbal means, she did assert control over her own body. She also sent a powerful set of messages to her shipmates as she languished among them ether recovering or expiring. The violence of an eighteenth century shipboard abortion was an intimate act, but it would not have been private.

And what of the man held captive on the Unity, who, amidst a shipboard rebellion, chose to jump into the sea? Yes, he deprived the voyage and its stakeholders of valuable cargo as the author notes in her treatment of suicide. But what was he telling his fellow captives? Even as they chose revolt, he drowned himself. What message did he send?

Mustakeem’s work provides us with a way to re-member the dead. She exhumes their stories and lays before the reader an autopsy of their experience. In Slavery at Sea, the dead and brutalized are not nameless dashes in ledgers meant to record profit losses, but humans who moved through and succumbed to layers of cruelty. Excitingly, her work with violence as a language presents a rubric for mining the ways that the enslaved, those who endured and those who perished, spoke to each other during their passage across the Atlantic. For scholars of resistance and revolt, like myself, she provides another way to read violent action that includes a range of practices and both male and female participants. Finally, her work allows us to sit with the dead, to listen to them and the stories their bodies tell, so that we might understand and better know how to remember them.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.