Private, Public, and Vigilante Violence in Slave Societies

This essay is the first post in a four-part series concerning the triumvirate of violence in slave societies. The first part will examine private violence, the second part looks at public violence, the third at vigilante violence, and the fourth part will demonstrate the ways in which these forms of violence carried over into the Reconstruction Era and beyond.

***

In Wetumpka, Alabama, just one year prior to secession, an illiterate poor white named Franklin Veitch “was dragged down to the margin of the river, laid across a log, and whipped by a throng of blackguards.” Not content with using their slaves to humiliate and punish the impoverished white, the local vigilance committee—led by the most affluent slaveholders in town—ordered that Veitch then be stripped naked and ridden on a rail. “From the lintel of his own door he was repeatedly hanged until he was black in the face,” a source reported, making the fact that Veitch survived the ordeal nearly unbelievable. While the local master class had once charged the poor man with “being a negro, and, afterwards, with associating with negroes,” his particular offense this time was one of the most common charges throughout the Deep South. The owners of flesh ordered and executed the torturous violence, the vicious beating, and the savage lynching all due to the unfounded allegation that Veitch “sold liquor to negroes.”1

Complicating their ability to control the region was the fact that slaveholders increasingly had to grapple with trying to achieve segregation, as was evident in Veitch’s case. This task proved impracticable for several reasons. Poor whites and African Americans not only drank, socialized, and slept together, but because they were shut out of the formal economy they also created an entire underground economy in which they traded liquor, food, and services. The racial ambiguity of growing numbers of southerners only exacerbated the situation. Certainly by the 1840s and 1850s, generations of interracial sex had produced an entire class of people who were difficult to immediately categorize as either white or black. With the prevalence of slave hiring, the presence of free blacks, and the darkened skin of poor whites who generally labored in the hot southern sun, the region’s racial hierarchy was becoming unwieldy and unenforceable. Lines separating the supposedly dialectic categories of black and white, slave and free, were gradually becoming blurred and in some cases even indistinguishable. Slave owners truly did not know what to do.

As segregation became more difficult for the master class to maintain, southern laws placed increasingly strict behavioral regulations on sex, drinking, gambling, and other social interactions, further monitoring poor whites and blacks in an attempt to keep them separated. Yet the criminal justice system alone could not keep one of the world’s largest slave systems running efficiently. Instead, the master class needed a total system—of policing, surveilling, and torturing poor people.

The maintenance of the Deep South’s slave societies required the constant threat of bloodshed. Policing both groups, slaveholders set up a three-tier “punishment” system that effectively prevented riot and rebellion. First, as independent, individual citizens, masters and overseers privately whipped the underclasses. Second, slaveholders used the criminal justice system to incarcerate and brutalize individuals for debt and non-violent behaviors they deemed illegal. Finally, affluent whites established an intricate system of vigilante brutality—complete with slave patrols, vigilance committees, and minutemen groups—to buttress the other systems and ensure that the masses were rendered either powerless or terrified. To truly understand southern social control, therefore, scholars need to stop focusing solely on the legal system and instead recognize that these three methods of violence were all interrelated. Slaveholders so nearly perfected this system that even after emancipation they employed this triumvirate of violence once again to reestablish control over the region.

Part I: Private violence (meted out by individual slaveholders, overseers, and masters or employers)

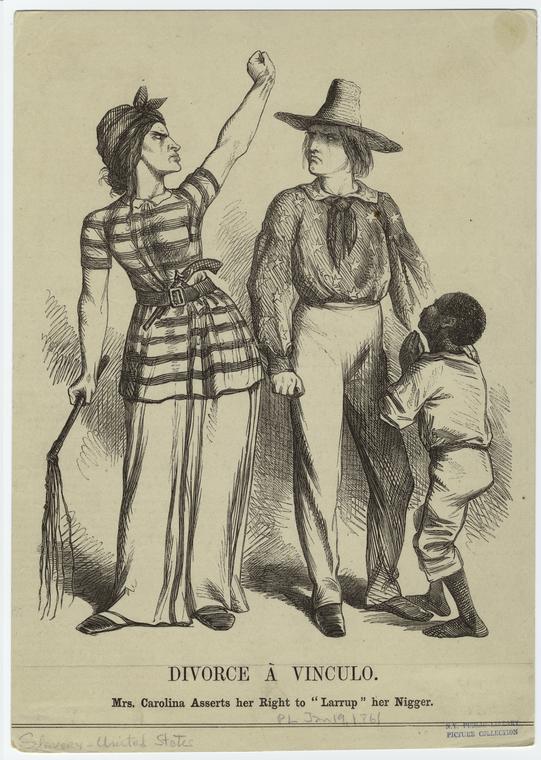

With recent works by historians on capitalism and slavery in the South, the extent of personalized violence—between masters and overseers against slaves—has been laid bare. The whipping and torture of the enslaved was widespread, heinous, and frequent. Works Progress Administration interviews with former slaves are filled with tales of children watching in horror as their mothers were whipped and beaten, and slave narratives confirm how often the enslaved were lashed. Once the whipping was over, many masters and overseers sought to prolong the suffering of the enslaved by literally pouring salt into their painful wounds. And whippings were not the only form of punishment—often, even more heinous forms of violence took place, from water torture to a combination of physical and psychological terrorism. While historians may never know the full extent to which violence pervaded the relationship between masters and the enslaved, the parts we do know are harrowing and haunting, particularly ruthless and cruel.

It should be noted that poor whites, too, were susceptible to a beating from an employer or master, though to a far, far lesser extent. Indeed, the long-standing correlation between labor and privately-sanctioned violence in the South must be acknowledged, as it becomes incredibly important in the era of emancipation. Whether slave, servant, or bound or even “free” laborer, workers lived in constant fear of brutality, even in early childhood.

Future President Andrew Johnson, for example, was whipped when he was a boy on many occasions by middle and upper-class white men. As a poor white child he had been bound out to a master who often punished him unmercifully, but he was whipped by a local slaveholder as well. These stories show that the field desperately needs more studies of the different types of unfree labor in the nineteenth-century South, as well as a reassessment of the violence associated with that labor. One useful starting point would be the examination of county/parish-level coroners’ reports and inquisitions. How individuals come to their deaths reveals a surprising amount of information about a society, and often powerful men could maim and murder with impunity. From the extant records, it certainly seems as if the vast majority of wealthy murderers were never brought to trial in court—instead, a small coroner’s inquest would inevitably rule the murder either accidental or a result of natural causes, allowing the rich to walk away from their heinous crimes completely unscathed. Indeed, not only would a thorough examination of coroners’ reports drastically increase the overall murder rate for the antebellum South, it would also reveal that American slavery was even more exceptionally brutal than previously thought, with the enslaved frequently suffering violent deaths at the hands of white men.

Private violence, though, must be understood as just one part of the triumvirate of violence that characterized slave societies. Even with all of the lashings and violence from masters, overseers, and employers, the southern elite still had at its disposal both public and vigilante violence as well. All three methods buttressed each other, helping slaveholders and their allies maintain tight control over the region, effectively helping to prevent and quell any type of uprising.

Keri Leigh Merritt is a historian of the 19th-century American South who works as an independent scholar in Atlanta. Her first book, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, will be published in 2017 by Cambridge University Press. Follow her on Twitter @kerileighmerrit.

- R.S. Tharin, Arbitrary Arrests in the South; or, Scenes from the Experience of an Alabama Unionist (New York: John Bradburn, 1863), 52. I define poor whites as owning neither land nor slaves (excluding younger sons of the affluent still awaiting inheritances) and estimate their numbers at about a third of the Deep South’s white population. They were often condemned to generations of cyclical poverty, as they simply could not compete with brutalized slave labor and had no real place in the slave economy. ↩

Thank you for the article. We need to dive into our history, now more than ever! So much of this is being played out right now. And it will happen over and over again, until we learn.

Thank YOU for reading – hope you will like the subsequent parts over the next few months. Have a great day!

I find this article to be an appropos intervention into the historiography of violence during slavery. It’s really pushing me to think about the myriad forms of violence that plagued the nation. I wonder what a transnational perspective would look like….? In other words…was American violence more heinous in comparison to other parts of the world? What made American violence distinct or cliche? Can we argue that the American South represented the most violent region in the nation?