Finding Agency in Unexpected Places

Ezekiel Price was a notary public in Boston, Massachusetts whose career spanned from the 1750s until the 1780s. He dutifully served in his position through war, economic upheaval, and revolution. Although partly motivated by self-interest since he sold marine insurance, Price also fulfilled his mission to the public, recording bills of sale, testimonies of lost ships and cargoes, and receipts for goods from across the Atlantic world. Interestingly, in between harrowing tales of great tempests and commercial documents in at least five different languages, Price also recorded manumission certificates, receipts for the sale of slaves, and testimony regarding enslaved and free blacks.

This post examines Price’s notary books to explore black mentalités in the eighteenth century. Unlike my previous posts, this piece will be a bit more methodologically focused, making an argument not only about the historical lives of early African Americans, but also how we can use context and different types of documents to undercover lived experiences and pre-modern black intellectual life.

To understand why Price’s records can be useful for understanding early black interiority, we have to explore the place and purpose of notaries in early modern English law. Unlike continental European nations where notaries played a similar role as attorneys, British law was much more ambiguous. Notaries had long been part of British legal life, but, by the seventeenth century, they were largely relegated to commercial affairs. 1 Across the British Empire, local government and royal officials appointed notaries public, who, like Ezekiel Price, took careful note of business transactions. Although Anglophone notaries did make copies of other types of documents, it was relatively rare.

Why, then, do so many records concerning African Americans appear in Price’s notary books? Surely, enslaved people were objects of commerce and there are many bills of sale for slaves in his records. That does not, however, explain the large number of manumission certificates and testimony regarding slaves and free blacks. It is in these documents, I contend, that we see initiative and agency among black Bostonians. Although Price was rarely as meticulous as another Boston notary who made sure to record when entries were “made at the request of” various parties, it is not hard to envision blacks approaching Price and paying him to record and duplicate important personal documents. 2 Indeed, one of the few cases where Price did note who initiated the notarial process was a document recorded “at the desire” of an enslaved woman named Lettice stating that her son would obtain his freedom at the age of 26.

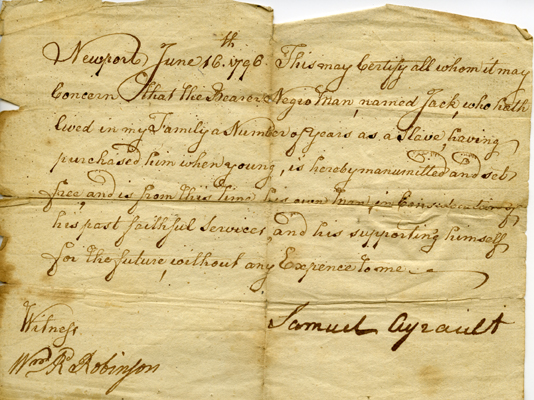

Most of the documents that slaves and free blacks brought to Price to record relate to two themes: freedom and property. While the first, freedom, may seem obvious given Price copied 14 manumission certificates between 1754 and 1779, other documents also attest to the drive for blacks to secure freedom for themselves and their families. Lawrence Hill, a free black, for example, made sure to have Price record the receipts every time he purchased one of his children from his wife Mary’s master, Sylvester Gardiner. All told, Hill purchased three of his children out of bondage.

Price’s notary books contain interesting discrepancies that help to understand the nature of black freedom. The last manumission recorded by the notary, for example, was in February 1789 for a man named Charleston who purchased his liberty from his master. Yet, the actual date on the document was 7 May 1777. Why did Charleston wait nearly 12 years to register his manumission certificate with Price? Perhaps Charleston’s copy was becoming worn or he feared losing it. Yet, even these practical concerns speak to a deeper issue—a problem also found within Price’s records. Beginning in the 1760s, Price copied a number of receipts for slave sales outside the colony. Boston slaveholders began selling their chattel to colonies in the American South and the West Indies, and Price has bills of sale for slaves to the Carolinas and Jamaica. As slavery became less profitable in the northern colonies like Massachusetts and slaves began challenging their status through petition campaigns and filing lawsuits for their freedom in the era of the American Revolution, many Boston masters saw the writing on the wall and sold their slaves to extract the last bit of wealth out of their bondsmen and women. Moreover, like the more famous stories from the antebellum period, unscrupulous whites kidnapped free blacks and sold them into slavery. Registering a manumission certificate with Price, then, was one way to ensure one’s freedom would be permanently recorded and could always be used as evidence of that liberty.

Upon obtaining their freedom, many blacks turned to Price to help them record and lay claim to property. In this sense, freedom was only the first step. Property would allow freed men and women to enjoy that liberty and, more importantly, secure independence within white society. There are two instances of free blacks looking to secure property in Price’s books. The first involved a man named Charles whose former master gifted him a small Hopkinton, Massachusetts farm in his will. Charles had Price record three different testimonials from white neighbors acknowledging his inheritance. The other document belonged to a freedman named Caesar Marion, whose master, retired blacksmith Edward Marion, not only manumitted his slave in 1769, but also gave Caesar all of his tools and use of his shop. Caesar then used this property to go into business for himself, becoming one of the few black property owners in Boston listed in the 1771 Massachusetts tax assessment.

Today, Ezekiel Price’s notary books are housed at the Boston Athenaeum. While the documents copied at the behest of black Bostonians make up a relatively small percentage of records contained in the seven volumes of notarial registers, they do give us insight into the thoughts and concerns of early African Americans, namely a desire to secure their freedom and property rights. Nevertheless, these volumes are also an unexpected place to find marginalized people and it is striking to see so many in Price’s books as more than victims of an unjust system. Their presence suggests that slaves and free blacks in Boston understood the place of notaries in English society and appropriated a commercial institution for their own purposes.

For that reason, it is important for historians of early black life, especially those studying an era before mass literacy, to carefully comb through all records, even those that may not self-evidently relate to people of African descent. Moreover, it is important to not only ask why these records exist, but also who initiated their creation and why it mattered to those initiators. In the end, the existence of black voices in Price’s records demonstrates that freed and enslaved men and women understood the precariousness of being free and black in a society that steadfastly refused to acknowledge black freedom and sought to protect their hard won liberty and independence through all the means available.

Thank you for this informative article.

Raymond Sean Walters, Fellow of The Phylaxis Society

http://thephylaxissociety.com/

Thank you for this valuable post. Prince Hall and other black Bostonions laid a foundation for the modern African American community. I would love to find an index of who is mentioned in Price’s books

Very interesting work. Brief report of political activity by Caesar Marion/Merriam inside besieged Boston here.

great article about the history of the african american experience in the period. your use of the primary sources in your analysis shows the way to broadening how we critically use and think about a variety of documents. also nice use of the homer painting (1776) to illustrate the visualization of what freedom for african americans may have looked like in moment of that particular era.

Thank you so much for your work. Is it possible to pass on a list of the names referred to in the 14 manumission certificates? One 1762 probate from Cape Ann documents the sale of land and a dwelling house to Pompey Cummins with money held in trust for him for at least a year. Pompey or Pomp had been “willed his freedom by late said negro Servant’s mistress.” The property was purchased for eighty pounds. The deed was recorded in 1792.