An Unspeakable Toll: Relentless Violence and the Middle Passage

This post is part of our online roundtable on Sowande’ Mustakeem’s Slavery at Sea

In 1790, Thomas Trotter testified to a committee of the British House of Commons about the things he had seen while serving as a surgeon on board the slave ship Brookes in 1783. Among the stories he told was that of a West African man who had argued with the chief of his village. The chief, in an act of vengeance, had sold the man, his wife, his mother, and his two daughters into slavery. The entire family ended up on the Brookes, and by the time they arrived at the ship they showed obvious signs of trauma. Trotter observed that the women evidenced “every sign of affliction” while the man exhibited “every symptom of sullen melancholy” and refused to eat. Indeed, the man soon “made an attempt to cut his own throat.” Trotter sutured the laceration, but the man both tore out the sutures and tried to gash the other side of his neck. Trotter and the sailors working on the Brookes restrained the man and searched the ship to find the weapon he had used to inflict his wounds. They found nothing, and in light of the ragged edges around the man’s injuries and the fact that the man’s hands were covered in blood, Trotter could only conclude that the man had attempted to tear open his own throat using his bare hands. In case his captors failed to understand his motives, the man told Trotter that “he would never go with white men.” He continued to refuse food. He died about a week and a half later. The fate of his family is unknown (pp. 124-25).

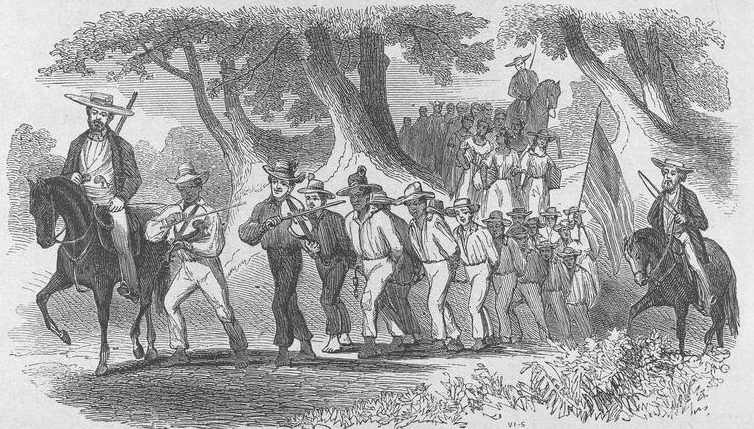

Sowande’ Mustakeem’s Slavery at Sea is filled with stories like these that force the reader to confront the despair, fear, grief, stress, isolation, vulnerability, and relentless violence imposed upon the millions of men, women, and children stolen from Africa and placed on European ships to cross the Atlantic Ocean so that they might serve as exploited labor in the fields of the western hemisphere. Bringing the histories of slavery and the slave trade into conversation with historiographies that speak to the history of capitalism, the history of the body, disability studies, the histories of gender and sexuality, medical history, and notions of open water itself as a historical landscape, Mustakeem has made a thorough, bracing, and often profoundly disturbing case for how systematically the experience of the Middle Passage remade captive Africans. Focusing particularly on the British and American trade of the eighteenth century, Mustakeem demonstrates how merchants, sailors, and surgeons collaborated to produce abominable material conditions on slave ships and to abuse and terrorize their victims, breaking them down in body and soul over the course of months as part of what she refers to as the “human manufacturing process” of the “slaving industry” (p. 7).

Slavery at Sea serves as a departure from most studies of the transatlantic slave trade in numerous ways, among them the emphasis Mustakeem places on the diversity of the populations subjected to its miseries. Merchants, investors, and plantation owners mostly wished to ship and purchase the bodies of young male slaves who were strong and healthy enough to work, along with a smaller number of young female slaves who were able to reproduce and who white people found aesthetically pleasing. But those who swung the net of captivity that swept up Africans for sale were far less discriminating. Mustakeem stresses how nearly anyone could be caught in that net, and how we misread the trade if we focus only on individuals who emerged on the American side of the Atlantic from maritime torture chambers like the Brookes. We may know relatively little about those deemed too old, too young, too sickly, or too feeble to be of great financial value to the commercial operators of the slave trade, or about those with physical disabilities or bodies considered too “irregular” to be sold. But we do know that the trade entirely upended the lives of many such people. At best, they were considered “damaged” and sold at a discount, and at worst they were considered disposable “refuse.” Either way, their relatively negligible financial value left them exceptionally liable to be abused, discarded, or even killed, and Mustakeem smartly observes how the visibility of such treatment both took an unspeakable toll on those who bore its brunt and intensified and reinforced the terror felt by others who witnessed it.

In Mustakeem’s telling, the transatlantic trade was totalizing not only in the scope of the human population it comprised but also as a physical and psychological ordeal. These were not separable elements of the experience, and among the more powerful elements of Slavery at Sea is how Mustakeem details the ways the shocks of the trade applied to the body and the mind alike in a kind of demented feedback loop. Captives confronted hunger, thirst, and exhaustion, and they were tossed about by unpredictable weather conditions. They were poked, prodded, pushed, and smacked. They spent long periods of time enchained in dark, claustrophobic, filthy, and stifling spaces filled with vermin and parasites that spread disease, and they were crammed together naked in those spaces such that everyone was exposed to the open wounds and bodily fluids of their fellows. Sailors and ship captains inflicted beatings, tortures, and rapes, and the surgical efforts to ameliorate illness were themselves painful treatments such as bleeding, purging, and blistering. The cumulative impact of such punishment, contagion, and insalubrity debilitated the body in almost every imaginable way, but it was also humiliating, terrifying, and disorienting. Some individuals withdrew into themselves and became depressed, while others became so unbalanced that they went insane or so filled with anguish and sorrow that they became insensible due to what we would now consider broken hearts. That mental and emotional decline only made the bodies of captives even more susceptible to weakness and made ship personnel even more likely to mistreat them, which in turn yielded greater psychological derangement. And so it went until those who managed to survive passage across the ocean often arrived battered, broken, and scarred. In Mustakeem’s account, we must push the formative period in the process of unmaking a person so that they might be kept in slavery backward from the experience of “seasoning” on the plantations of the western hemisphere. It began from the moment of capture itself.

The relentless bleakness of Slavery at Sea does stand in significant contrast to accounts of the transatlantic trade that foreground the resilience of those who survived it, the struggles to remake community and culture amidst forces that would have stripped them away, and the ways the experience of the trade helped lay the foundation for new black histories in the Americas. Mustakeem is hardly unaware of those realities, of course, and the devotion of several chapters in Slavery at Sea to the resistance captives mounted to their circumstances points to the fact that despondency was only one response among many to being held prisoner on a slave ship. Still, whether manifesting as shipboard insurrection, poisoning, abortion and infanticide, suicide, hunger strikes, or other means of self-harm, efforts by enslaved Africans to reassert some measure of control over their own lives remained grounded fundamentally in the violent terror of their reality.

To Mustakeem, however, keeping violence at the center of the story is not about affirming the indignities and degradations of the Middle Passage such that we neglect to consider the significance of the astonishing endurance of those who lived through it. It is, rather, about pushing past an account of the transatlantic trade in which resiliency becomes its own form of romance or one in which shame becomes overwhelming to the point where it becomes nearly an abstraction. By presenting the trade and the terror that suffused it in so viscerally concrete a fashion, Mustakeem forces us to remember that the slave trade was not merely a symbol or a historical artifact that might be boiled down to numbers and profits and loss. It was about individual people and their pain. And by remembering those people and that pain, we impart to them a dignity they surely deserve.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Black Perspectives is excellent and the consistent quality of the scholarship it demonstrates is exemplary. Every single contribution I have read with intellectual profit. It is deserving of the broadest possible dissemination. It is a well -designed publication, thoughtful in selection of topics, and I look forward to each edition.

Much success to Black Perspectives.

Al-Tony Gilmore, Ph.D.

Historian Emeritus

National Education Association