Fugitivity, Refusal, and Visual Captivity: A Review of Tina Campt’s Listening to Images

I will never forget the unnerving feeling that washed over me when I first saw Sandra Bland’s mug shot circulating on social media. Some of the photographs’ sharers expressed the desire to avoid Bland’s death going unremembered, as is the case for many black women and girls killed by the state or vigilantes. Other users shared it explicitly contemplating whether or not the photo was taken postmortem and thus staged by police in Waller County, Texas. Curiously, I found myself inspecting the image for signs of life and death. I scrolled between photographs in which I could be sure Bland was alive and the haunting image of her under arrest and possibly dead. I wanted to know if she was dead to indict the police, but why did I need to see her potentially lifeless body to know that the police are violent and responsible for too many of our premature deaths; that they rehearsed killing her when they took her into captivity; that they likely killed her for being “defiant”?

In response to the social media outcry, Waller County officials released surveillance footage of Bland as she was processed for her mug shot. For me, the release exacerbated the matter in the aftermath of the social media allegations. Though the police’s release of the footage was designed to corroborate their account of Bland’s final hours and to assure the public that Bland committed suicide, the release reinforced my discomfort because of the ways the still and the footage resonated with the history of macabre visual culture in the service of gendered forms of murderous, anti-black violence. If death marks the ultimate social stillness, then images of black captivity that abound in the archives of state bureaucracies from the United States to South Africa function as a kind of mortuary log.1

Taken together, these archives, from pre-photographic etchings to modern digital footage, anchor visual captivity: the practices of social verification, truth, and power established through the visual (as well as the other sensory modes sublimated in the service of seeing), that un-genders black bodies, renders them as flesh, and leaves them available and arrested; open for violation and mutilated; dying and dead.2 And yet, if the Waller County police released the footage of Bland’s arrest to demonstrate a black woman in confinement, the visual archive of Bland’s last hours also illustrate her refusal—a tense relation through which she sought to negotiate the terms of her embodiment in relation to visual and physical captivity.

Tina M. Campt’s latest book, Listening to Images, provides a powerful set of theoretical and methodological tools for historicizing and unpacking the kinds of photographic archives of which Bland’s images are a recent, prominent, and disturbing example. Campt investigates various archives of mundane images including mug shots, colonial ethnographic images, and passport photographs outlining a generative and creative archival praxis. Rather than resting with the description of the genres of photography like mug shots as they function to render black communities captive and silent, Campt presses us to view them “as conduits of an unlikely interplay between the vernacular and the state”–as exhibiting the tendencies of domination and also revealing constrained possibilities for fugitivity; circumscribed self-fashioning; even (futile) efforts in becoming otherwise.

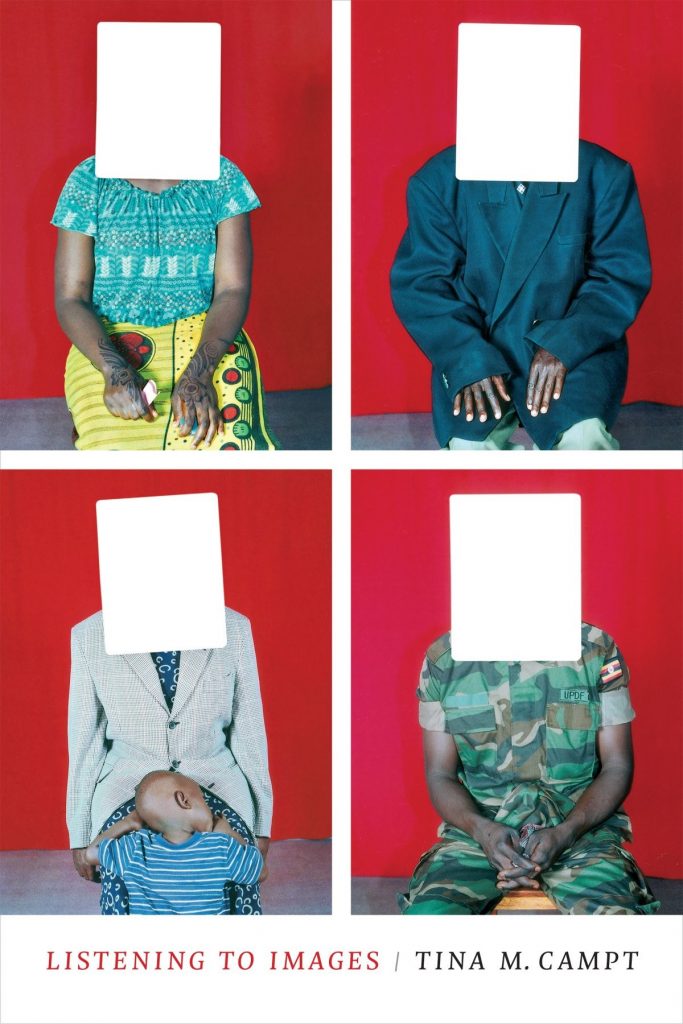

In the opening chapter of Listening to Images, Campt brings together a series of seemingly disparate photographs: images from post-conflict Uganda in which the faces have been cut out to create various forms of identification; passport photos of West Indian men taken in the postwar period at a studio in the Balsall Heath section of Birmingham, England; and a photographic essay shot in the same neighborhood of Birmingham to capture the seedy underground of sex workers and “pimps.” Campt analyzes these images to elaborate what she calls a black feminist grammar of futurity, whereby we might think through and establish a “politics of prefiguration that involves living the future now—as imperative rather than subjunctive—as striving for the future we want to see, right now, in the present.” Moving away from simply looking at the eyes of each subject (which is impossible in the first set because they are faceless), Campt finds in the hand gestures and sartorial choices of the first set and in between the suit and tie respectability of the studio passport photos and images of similarly clad “criminals” from a few blocks away in Birmingham, the path to listening to images. Rather than simply taking them at their ascribed value in over-determining black life, Campt listens to the “hum” of serial photographs.

In the second chapter, Campt deals with another mode of photographic rendering used to hold black people in a form of visual captivity: ethnographic images. She uses them to reach sophisticated theoretical insights about writing subjectivity outside of simple confinement, agency, or resistance. While ethnographic photos are “images intended to classify types rather than identify individuals,” Campt uses them to elaborate the grammar of black feminist futurity through her notion of stasis— “the embodied postures of the subjugated as visible manifestations of psychic and physical responses (rather than submission) to colonization and the ethnographic gazes.” Taken together, Campt views these modes of circumscribed self-fashioning as what she terms “reassemblage in dispossession” or quotidian, small-scale edits on the racist social order to partially or temporarily reconstruct the position of the dispossessed.

In the third chapter, Campt brings together two archives of mug-shots: the first from the 1890s in South Africa during the period in which apartheid began its consolidation; and the second a set taken of Freedom Riders in Mississippi arrested for their efforts to end formal apartheid in the US South in the 1960s. Campt works these images to round out her mode of haptic engagement with photographs whereby the haptic describes the “multiple forms of contact and touch” related to photography. “Attend[ing] to the quiet frequencies of austere images that reverberate between images, statistical data, and state practices of social regulation,” Campt seeks to engage the images through a different mode of the senses in order to resist the “the silencing effects of the serial bureaucratic grammar of the archive.” Taken together, engaging the “haptic temporalities and quiet frequencies” of these archives challenges the weight of the archive and temporarily interrupts their power to fashion subjects through the dominant visual tropes that they naturalize. Engaging these frequencies allows Campt to locate fugitivity, or “a refusal of those catalogued… to be completely captured or reduced to the archival grammar of criminality or the seriality of type.”

Finally, in the coda, Campt joins her childhood memories of photographs of Terrance Johnson’s tragic case in Prince George’s County, Maryland and contemporary social media generated images whereby black youth stage and “practice refusal.” In attending to these images, Campt returns to the threads developed throughout her grammar of black feminist futurity, asking “[h]ow do we create an alternative future by living both the future we want to see, while inhabiting its potential foreclosure at the same time?” Campt concludes with her operative definition of freedom as “an existential grammatical practice of grappling with precarity, while maintaining an active commitment to the… labor of creating an alternative future.”

Tina Campt’s stimulating new work is a must read in a flurry of exciting work at the intersection of Black Studies and visual culture. Campt’s work joins Simone Browne’s Dark Matters on surveillance, Krista Thompson’s Shine on street and other forms of popular photography in the diaspora, and Nicole Fleetwood’s On Racial Icons on the generation and circulation of black iconicity through photography in the United States. Taken together, these works open the production and circulation of photographic images as a set of complex social processes that index and help produce a wider social order in which black communities are vulnerable but also wield insurgent forms of power.

- According to Saidya Hartman, “to read the archive is to enter a mortuary; it permits one final viewing and allows for a last glimpse of persons about to disappear.” Lose Your Mother (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2007), 17. ↩

- See Weheliye’s elaboration of Hortense Spillers concept of pornotroping. Alex Weheliye, “Depravation: Pornotropes,” Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014): 89-112. ↩

Great article! I attended grammar school with Sandra Bland’s mother. Imagine my shock to learn that this was the daughter of a childhood friend.

Childhood friend or not, however, her story is one of great sadness as with many others.

I can only hope and pray, and believe me my prayers come in abundance, that one day this madness will all end.

Thanks again for well written piece.

KC

Thanks for this engagement !