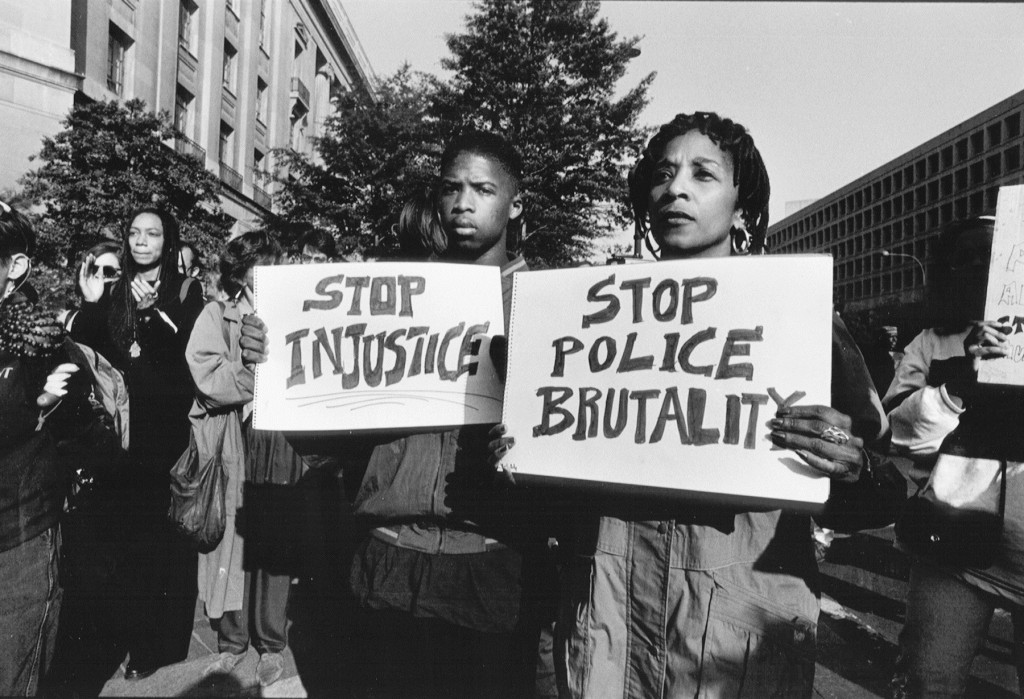

“What’s Going On?”: Race, Brutality, and Injustice Since Rodney King

On April 2, 1939, legendary R&B and soul singer Marvin Gaye was born. Known for a body of masterpieces, his musical genius and songs span an impressive thematic continuum from romance and sexual liberation to social justice. “There’s too many of you crying […], / there’s too many of you dying […]. / Don’t punish me with brutality,” he powerfully renders in a beautiful and melodic yet melancholic cadence in the song “What’s Going On?”. Released in 1971 to address police brutality, Gaye’s lyrical rendition is far from inconspicuous in its political engagement and critique of racial tensions, anti-black violence, war, and domestic tragedies and dis-ease.

As circumstance (and perhaps irony) would have it, six years prior to the release of this song, Rodney King, like Marvin Gaye, was born on April 2. Yet, it is in March of 1991 when King would infamously enter the spotlight as the victim of a horrific, violent beating by the Los Angeles Police Department. This concretized for newer generations the deep social ills, racial tensions, and racialized violence iterated by Gaye. But it also managed, in unprecedented fashion, to render black extrajudicial corporeal punishment, state-manufactured brutalities, and the terrorizing of black people for public consumption since King’s beating was captured on video. Yet, neither public defilement and violence against black bodies nor the spectacles of black bodies being brutalized were novelties. These occurred with frequency and impunity during the antebellum period, the Jim Crow and civil rights era, and beyond when blacks were routinely maimed, lynched, tortured, trampled, and killed while the imagery of these acts circulated, often deliberately. Even though racial profiling and police brutality had long existed, then, the fact that the beating of Rodney King was etched frame-by-frame onto video offered material evidence of what black people had long experienced at the hands of others and, more uniquely, from those who took an oath as officers “to serve and protect.”

And yet, in the twenty-first century, what is the status—what has changed—since Rodney King’s brutal beating by police and his subsequent call for us to “all just get along”? We live in a moment in which new footage and videos circulate of black men and women, such as Walter Scott, Rekia Boyd, and Alton Sterling, among others too numerous to enumerate, being beaten or, far too often, killed. These images, more often than not, saturate news headlines as well as our nation’s cultural fabric. We live in an age in which women in Texas and California are manhandled, body-slammed, and beaten by police in broad daylight or where girls—whether at pool parties or in high school classrooms, while wearing swimsuits or seated at desks—are violently tossed and slammed to the ground. Neither their gender, age, or intersectional identities as black girls and women make them immune to state violence or protect them from brutalities at the hands of the police or others. This is, indeed, also the age in which young black men like Philando Castile can drive with loved ones in one moment and in the next be stopped by the police as the public witnesses their death at the hands of an officer in real time on social media. And, alas, these are times when folks like Darren Rainey, 50 years old, mentally ill, and in the custody of the state, are subjected to a forced scalding-hot shower by corrections officers. Even as Rainey shouted, “I can’t take it anymore”—not dissimilar to Eric Gardner’s assertion, “I can’t breathe”—prison guards did not cease. They did not remove him, which resulted in Rainey’s unquantifiably cruel, gruesome, and unwarranted blistering death.

These instances all make apparent, with legibility and the utmost transparency, the structural, systemic, ornamental, and routine mistreatment of black people, as well as the failures of the law and the American justice system recently made more evident. On March 31, an officer was sentenced to 40 years in prison without parole for manslaughter in the death of a 6-year-old and 15 years for attempted manslaughter of an adult. This is the case of Derrick Stafford, a 33-year-old deputy city marshal in Marksville, Louisiana. The officer sentenced is black. The victim and survivor are not. This has led some to rightfully question the role of race in who walks away unsentenced in this case and others, amid a host of inquires. In an age when police shootings are far too commonplace, what is foreign—what we seldom see in American society and in our legal justice system—is indictments of officers or especially their being sentenced to jail-time. We protest non-indictments, mistrials, and other insufficient verdicts. We long for justice to be served in these cases. We yearn for concrete signs that the law is not discriminatory. Yet, black folks appear to remain, by and large, on the “receiving end”: that is, being beaten and shot by police who, regardless of race, customarily walk away without justice being served. Or, in the case of Stafford—an officer who was not acquitted, as has been the case with so many other police-involved killings—bound to the full extent of the law.

We need justice and equality, not partial justice or justice dictated by one’s race or status, to protect each and every individual under the law and, equally important, to hold all accountable, without exception to or double standards with regard to race. We need justice, fairness, and equal treatment, and we need it to apply equally to all Americans. Otherwise, we will continue to ask generation after generation, decade upon decade, and tragedy after senseless tragedy, “What’s going on?”

I’ve been wondering what it was gonna take to wake our people up. Few of us been

awake and trying to awaken others but we are scorned and our people are so deeply

programmed, that I actually think most of them, not some, but most think this is just

the way its gonna be. They have no vision and therefor will never climb out of the box.

As much as I hate to say leave them by the way side, perhaps that may be a necessary

truth fact, and hard situation that will have to be what it is. Peace!