African Americans and the Congo: An Interview with Ira Dworkin

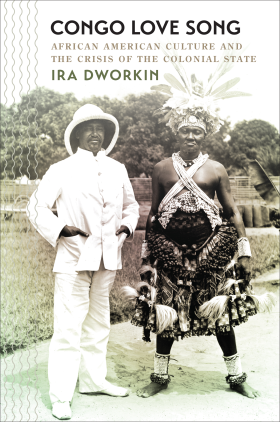

In today’s post, Marius Kothor, a PhD student in the Department of History at Yale University, interviews Ira Dworkin on his new book, Congo Love Song: African American Culture and the Crisis of the Colonial State (University of North Carolina Press), which was a finalist for the African American Intellectual History Society’s Pauli Murray Book Prize. He currently teaches in the department of English at Texas A&M University. He previously taught at the American University in Cairo, and as a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He is the author of Congo Love Song and the editor of Daughter of the Revolution: The Major Nonfiction Works of Pauline E. Hopkins (Rutgers University Press); Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (Penguin Classic); with Ferial Ghazoul, The Other Americas, a special issue of the bilingual Cairo-based journal, Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics; and with Ebony Coletu, On Demand and Relevance: Transnational American Studies in the Middle East and North Africa, a special issue of Comparative American Studies. Follow him on Twitter @CongoLoveSong.

In today’s post, Marius Kothor, a PhD student in the Department of History at Yale University, interviews Ira Dworkin on his new book, Congo Love Song: African American Culture and the Crisis of the Colonial State (University of North Carolina Press), which was a finalist for the African American Intellectual History Society’s Pauli Murray Book Prize. He currently teaches in the department of English at Texas A&M University. He previously taught at the American University in Cairo, and as a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He is the author of Congo Love Song and the editor of Daughter of the Revolution: The Major Nonfiction Works of Pauline E. Hopkins (Rutgers University Press); Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (Penguin Classic); with Ferial Ghazoul, The Other Americas, a special issue of the bilingual Cairo-based journal, Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics; and with Ebony Coletu, On Demand and Relevance: Transnational American Studies in the Middle East and North Africa, a special issue of Comparative American Studies. Follow him on Twitter @CongoLoveSong.

Marius Kothor: There have been a number of important studies on Black internationalism that examine African American engagement with Africa in mostly conceptual terms. Congo Love Song, however, focuses on a specific region. What does a study of Black internationalism from one geographical location reveal that may be harder to see from a broader focus on Africa as a whole?

Ira Dworkin: In Congo Love Song, I wanted to focus on the Congo (the current Democratic Republic of the Congo and former Belgian colony) as a modern political entity in detailed ways that consider its specific cultures and histories. The Congo is an important case study for understanding the ways that African American engagement with Africa has never been exclusively conceptual, but rather has always attended to the particularities of multiple political landscapes. The African American relationship to the Congo is different from the relationship to Ethiopia, which is difference from the relationship to Egypt, which is different from the relationship to Liberia.

I did not want to make the argument that Africa is not an abstraction for African American intellectuals, activists, writers, artists, and communities in abstract terms. The sources that I rely on from archives of HBCUs and the Black press document many of the ways that African Americans in the late nineteenth century understood modern African politics with far more complexity and sophistication than white mainstream media today. Ultimately, I believe that this focus adds depth to our understanding of how Black internationalism not only has recognized Africa as a unified field, but has also engaged with the continent in all of its geographic specificity.

Kothor: Before the atrocities being committed by King Leopold’s regime came to light, many of the individuals examined in the book were eager to go on expeditions to the Congo. What was the initial appeal of the Congo for the African Americans who went or expressed an interest in going?

Dworkin: The initial appeal of the Congo was a result of the particular machinations of King Leopold II of Belgium and his international supporters, who carefully curated the public illusion that the Congo was l’État Independant, an entity that supposedly stood outside of more familiar depravities of European colonialism. Historian George Washington Williams’s interest, for example, preceded the Berlin Conference of 1884 to 1885 with the hope that the Congo would emerge as an independent state under Black leadership similar to Liberia, whose history he studied (and criticized). In late 1889, Williams enthusiastically recruited Hampton students to work in the Congo, guided by an optimism that educated African Americans could perform a service to Africa consistent with the uplift mission of schools like Hampton.

Dworkin: The initial appeal of the Congo was a result of the particular machinations of King Leopold II of Belgium and his international supporters, who carefully curated the public illusion that the Congo was l’État Independant, an entity that supposedly stood outside of more familiar depravities of European colonialism. Historian George Washington Williams’s interest, for example, preceded the Berlin Conference of 1884 to 1885 with the hope that the Congo would emerge as an independent state under Black leadership similar to Liberia, whose history he studied (and criticized). In late 1889, Williams enthusiastically recruited Hampton students to work in the Congo, guided by an optimism that educated African Americans could perform a service to Africa consistent with the uplift mission of schools like Hampton.

However, as Williams became more immersed in planning his excursion, he realized that the Congo state was neither independent nor “free” (as it is often misnamed in English translation), and he soon became one of the first figures to expose Leopold’s maneuverings, publishing three pamphlets about the Congo, which John Hope Franklin reprinted in his biography of Williams. In this role, Williams publicly challenged the king and his imperial agents including Henry Morton Stanley and Henry Shelton Sanford (who founded the Florida town that bears his name, where Trayvon Martin was murdered). Still other African Americans, including the cohort that served on the American Presbyterian Congo Mission (APCM) beginning in the 1890s, were eager for opportunities to work with some autonomy in Africa. Such opportunities diminished during the first half of the twentieth century as colonial authorities considered African Americans as threats to European rule. Belgian anti-Garvey campaigners targeted Black missionaries. During World War II, Belgium forbid the stationing of Black soldiers in its African colonies, and even blamed a contraband photograph of African American military officers for an insurrection in Kananga.

Kothor: The chapter on George Washington Williams’s efforts to expose the violent mistreatment of Congolese people by King Leopold’s colonial officers illustrates your argument that opposition to imperialism was at the heart of African American engagements with Africa. What influence did this tradition of anti-imperialist activism have on future generations of Civil Rights leaders?

Dworkin: The foundational example of Williams grounds my argument that a politics of anti-imperialism, which during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries often incorporated seemingly contradictory projects of racial uplift, saturates the cultural discourse of the era in ways that are not always immediately visible. However, in direct opposition to popular assumptions of white primitivism, this activism has consistently recognized Africa as a modern political concern even when those politics are not definitively radical in contemporary terms.

I am especially interested in the direct influence of figures like William Henry Sheppard, whose APCM career effectively ended after his 1909 acquittal on charges of defaming a Belgian concessionary company. The scholar St. Clair Drake, for example, grew up in Sheppard’s hometown of Staunton, Virginia, and had formative childhood memories of Sheppard’s visits to his home as foundational to his interest in Africa. Much later, when Malcolm X sought to explain the violence in Kisangani (Stanleyville) in 1964, he cited (via Mark Twain) an 1899 report by Sheppard about the brutality he witnessed. Twain’s pamphlet King Leopold’s Soliloquy was sold by Lewis Michaux at his Harlem bookstore in the early years of Congolese independence, enabling Sheppard’s work to circulate among Black intellectuals and activists at a critical time. Even though Sheppard’s contribution was rarely acknowledged explicitly, by the 1960s there was a broad historical appreciation that the political crises of the early postcolonial era in the Congo were, as Martin Luther King Jr. explained, “a violent harvest […] planted across the years.”

Kothor: Althea Brown Edmiston’s linguistic work in the Kuba Kingdom stands out as an important example of how African American women engaged with the Congo. What does her story reveal about the opportunities available for African American women who wanted to do work in Africa in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries?

Dworkin: Althea Brown Edmiston is a remarkable figure whose career is representative of an equally remarkable cohort of highly educated African American women who worked on the APCM. As a linguist, Edmiston is responsible for the first dictionary and grammar of the Bushong (Kuba) language, which was a significant endeavor not only because of its scale (the volume published in 1932 ran 620 pages), but also because of her persistence. She worked on the book despite opposition from within the mission, over the course of more than two decades at a time when the Belgian authorities sought to supplant local languages like Bushong with Tshiluba, a regional lingua franca. Edmiston refused to allow her intellectual labors to be circumscribed by colonial policy.

Edmiston was preceded on the mission by a cohort of three Talladega College graduates, who, a decade earlier, were the first African American women appointed to the APCM. These included distinguished vocalist Lucy Gantt Sheppard, who in 1898 edited a Tshiluba hymnal Mukanda wa Misambu, nearly half of which was translations by African American missionaries. In 1909, the APCM published a Bushong hymnal that was entirely translated by African Americans. Soon thereafter, Edmiston and other missionaries translated African American spirituals such as “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” into Tshiluba. At a time when opportunities for African Americans to serve in the Congo were rapidly declining, this intervention helped insure that African American culture was embedded within the church’s religious, linguistic, and cultural work, a legacy which remains as several of these translations are still part of the independent Communauté Presbyterienne’s hymnal today.

This group of women nearly included recent college graduate Mary McLeod Bethune, who had her application to serve in Africa denied. According to their meeting minutes, the Northern Presbyterian (U.S.A.) Mission Board did not refer her to the Southern Presbyterian Church (U.S.), which supported the Congo mission, as it had other Black applicants. She stayed in the United States and began her distinguished career as an educator, yet remains an example of both the widespread interest of, and the limited opportunities for, African American women to work in Africa.

Kothor: As the title of the book suggests, in addition to shaping African American politics, the Congo (real and imagined) had a tremendous influence on African American visual art, music, and literary traditions. How have music, literature, and the visual arts functioned as bridges between African American communities and the Congo?

Dworkin: Amid a massive international human rights campaign in which African Americans played a central role, any invocation of the Congo—even seemingly apolitical aesthetic allusions––had deeply political resonance. For instance, the African art collection at Hampton was built through a purchase from former student William Sheppard, an important critic of Leopold’s regime. Significantly, Sheppard wrote about Kuba royal ndop statues whose importance and value he clearly recognized, but never “collected” them, which diverges from the dominant history of European and American museums. However, like the stolen Wakandan Vibranium that Erik Killmonger recovers in Black Panther, the exact statues ended up in the British Museum through other means.

Sheppard’s collection of Kuba textiles were used in home economics classes at Hampton in the 1920s and in the early 1940s when Hampton was a center for African American visual culture. (John Biggers and Samella Lewis were students there; Charles White and Elizabeth Catlett were visiting teachers.) The visual aesthetic Biggers developed over several decades and taught to generations of artists and educators at Texas Southern University emerged out of his engagement with the patterns and colors of Kuba textiles that he studied in Sheppard’s collection. The far-reaching formal and technical influence of the Congo is not separate from the political history of anti-imperialism.

Meanwhile, in the mid-1940s, Eslanda Goode Robseon was in the Congo. In the late 1940s, the great dancer and scholar Pearl Primus spent time in the Kuba kingdom where Sheppard and Edmiston had worked. These kinds of ongoing engagements set the stage for the frequent Patrice Lumumba elegies that emerged in the poetry of the Black Arts Movement, and in continuing references to Lumumba by X-Clan, Nas, David Banner, and perhaps most recently Black Thought (“Dostoyevsky”), which are part of wider ongoing networks of exchange that I have sought to document.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.