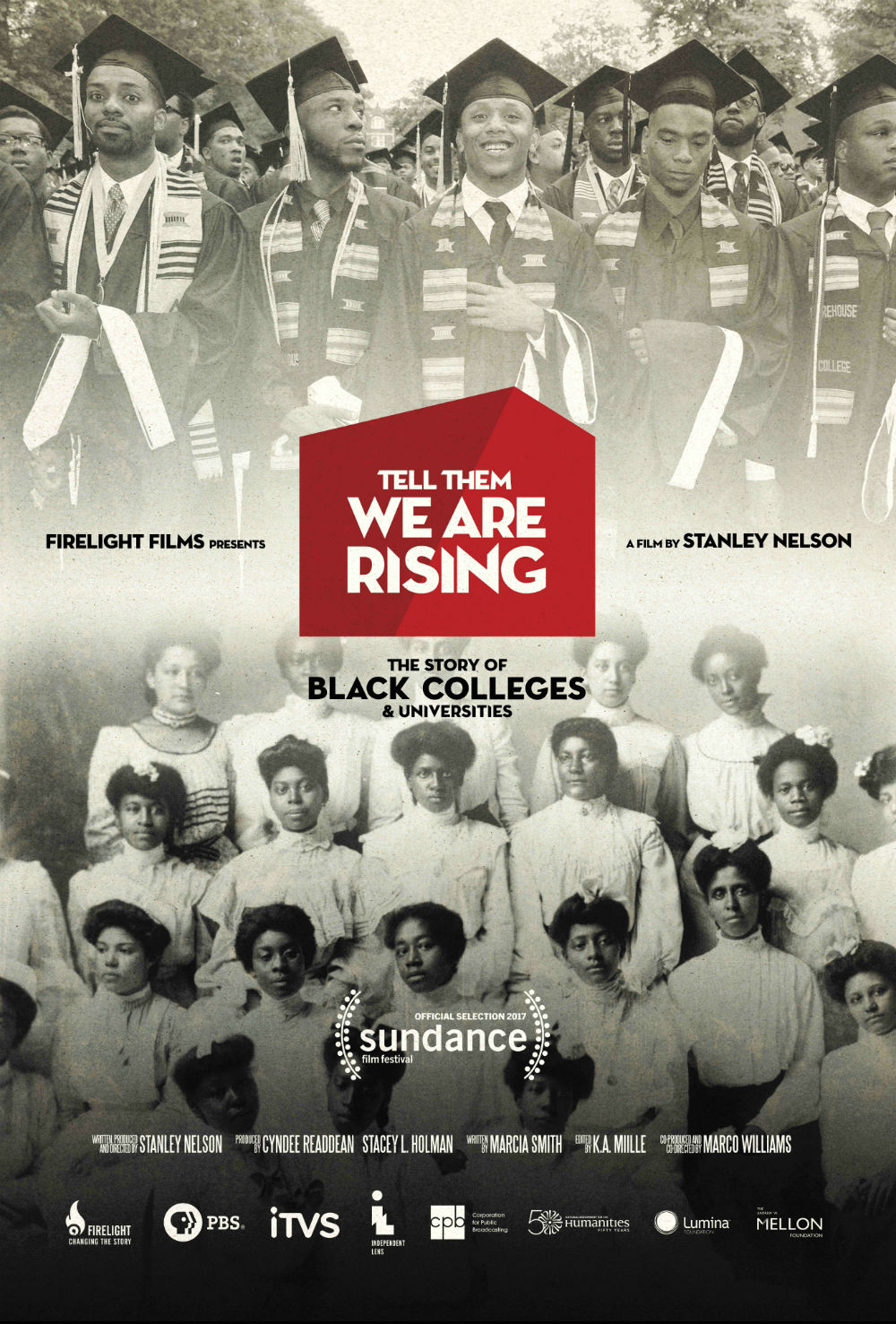

The Story of Historically Black Colleges and Universities

One of the most painful and haunting images that I recall from Stanley Nelson’s documentary, Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Historically Black Colleges and Universities, is the footage of a bare, abandoned Alonzo Herndon stadium on the campus of Morris Brown College in Atlanta, Georgia: neglected, overgrown with weeds, and graffiti splattered on its walls. I played football for the Atlanta University Center (AUC) rival team, Morehouse College, in that stadium against Morris Brown’s Wolverines football team. I saw Outkast perform at the stadium in 1998 on the Aquemini tour. (The Morris Brown College marching band is in the Rosa Parks video, and its gospel choir is featured on the classic Stankonia banger “Bombs Over Baghdad.”)

Tell Them We Are Rising shows what remains of Morris Brown’s faculty and students after financial neglect and internal scandals rocked the college and ruined its accreditation. Founded in 1881, this proud Black institution is now reduced to a few people seated around a table in the back of a church, trying to carry on Morris Brown’s educational mission and hoping for a rebirth.

There is a much more resilient and hopeful narrative at the center of Tell Them We Are Rising, but the demise of Morris Brown is an important story that also must be heard. Morris Brown is one of the few “for us, by us” Black colleges founded by Black educators of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and not by white philanthropists like many other HBCUs, including my alma mater. The fall of Morris Brown is a cautionary tale about the precariousness facing historically Black colleges in the twentieth-first century, and a call to protect and preserve these vital institutions.

I had the opportunity to see Tell Them We are Rising at the 2017 American Studies Association (ASA) meeting in Chicago, with director Stanley Nelson in attendance. A MacArthur “Genius” Fellow and an Emmy Award winner, Nelson is an experienced documentary filmmaker whose previous works include Jonestown: The Life and Death of People’s Temple (2007), Freedom Summer (2014), and The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution (2015). Tell Them We Are Rising is a thoughtful, engaging narrative about HBCUs that condenses 150 years of history to include more than one hundred different institutions. But that voluminous history also means this topic is too large for a treatment of ninety minutes. I found myself wondering what Nelson might have done with the budget and resources of a Ken Burns documentary. Even one of Burns’s “short” films, like the five-and-half-hour, three-part Prohibition, might have allowed Nelson a more adequate treatment of HBCUs.

Despite its limitations Tell Them We Are Rising is a must-see documentary about Black colleges, with Nelson using representative stories from HBCU history and interviews with administrators, alumni, students, and historians to convey the significance of HBCUs and the possibilities that lie ahead. Some of the notable talking heads include scholars such as Jonathan Holloway, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Marybeth Gasman, Johnnetta Cole, and James Anderson, whose 1988 book, The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935, is an essential tome on Black education in America. The film is presented in a chronological narrative divided into four sections: “Rising,” “Golden Age,” “An Audacious Plan,” and “Freedom.”

The film begins in the post-Civil War era that Anderson chronicles in The Education of Blacks in the South. Hungry for education and filled with faith in the education gospel, African Americans worked diligently to build schools with meager resources, as white supremacists looked on, wary of Black education as a “dangerous interference.” Predictably “Rising” includes the debates between Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois about the direction of Black higher education, whether it should be solely vocational (Washington) or also include a classical educational curriculum (Du Bois). Here again a longer film might have been able to accommodate a more nuanced version of this conversation that could include other voices such as Anna Julia Cooper’s, whose theorization of Black higher education incorporated the needs and desires of Black women.

The extensive section on Washington is warranted given what he accomplished in building Tuskegee University, and also because of his appeal to white elites who desired a Black labor force that was skilled, but not too educated, and certainly not educated in a way that would challenge white supremacy. Nelson’s film shows how Washington used photography to promote Tuskegee, deploying images that emphasized vocational and industrial education—a subtle reassurance to white leaders that Tuskegee did not have aspirations to contest the logic of Jim Crow. Washington’s career is indicative of the contentious relations between the Black college and the white philanthropists and politicians who controlled its purse strings then, and continue to do so today. Ralph Ellison brilliantly illustrated this in his 1952 novel Invisible Man, based on his own experiences as a Tuskegee student.

In “Golden Age” the film highlights the story of Black veterans returning from World War I and the violence they faced at home after risking their lives abroad. The experiences of Black soldiers would be one of the contributing factors in the launching of the New Negro movement. The Black college played a critical role in this New Negro era. A look through the literature of the Harlem Renaissance shows a roster of Black intellectuals and artists trained and cultivated at Black colleges. Du Bois is one exemplary example of a Black intellectual gaining an intellectual foundation at a Black college.

Born in 1868 and a mature man during the New Negro era, Du Bois is an icon of this era. Du Bois attended Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, where he earned his bachelor’s degree before attending Harvard University. His daughter Yolande Du Bois also attended Fisk. But Yolande’s time at Fisk is depicted in the documentary as part of a moment of student resistance to the old disciplinary models of HBCUs. Du Bois criticizes the Fisk model on behalf of his daughter, arguing that “discipline is choking freedom” when Black students are conditioned to be obedient to Jim Crow.

The section “An Audacious Plan” follows the development of a civil rights team at Howard University Law School under Mordecai Johnson—the first Black president of Howard—who hires law professor Charles Hamilton Houston, who in turn mentors the future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. Howard University was the incubator for the NAACP’s legal strategy in the 1954 landmark Supreme Court case Brown vs. The Board of Education, which fostered the desegregation of US public schools. The piercing irony of this story is that Howard’s success in the Brown case ultimately contributes to the problems facing HBCUs in the late-twentieth century. Desegregation is an important and necessary project for the equality and dignity of Black citizens, but it also brings a talent and financial drain on HBCUs as some Black students choose to attend predominantly white institutions. And star professors who once taught at Black colleges are now being hired and given more resources at predominantly white colleges and universities. Another related story left untold in the film is the theft of athletic talent away from HBCUs to sports programs at majority white colleges.

The harrowing section on student protests in the 1960s and 1970s, “Freedom,” shows the intergenerational conflict between the administrators and student protestors at Black colleges. The film uses the tragic murders of Southern University students Leonard Brown and Denver Smith by police during a protest on the Baton Rouge campus in 1972 as an effective representation of this period. Martha Biondi, the author of The Black Revolution on Campus (2012), appears in “Freedom” speaking about the protests at Southern and on other Black college campuses, where radical activists, inspired by the Black Power and Black Consciousness movements, challenged the assimilationist impulses of their administrators and pushed for curricular, political, and institutional changes. The latter part of the film connects those protests to the activism on Black college campuses today, which includes the Dream Defenders and Black Lives Matter.

The vibrant, colorful images of contemporary Black college life include interviews with current Black college students, graduations, step-shows, and sporting events. (The exuberant performance style of the HBCU marching band is another aspect of the HBCU story that deserves far more treatment than it could be given in the film). Throughout the film are funny and touching interviews with older HBCU alumni, including stories of elders who met and married in college, and who share their recollections of what their HBCUs meant to them.

HBCU alumni are a fiercely loyal bunch, and I suspect some alumni may be disappointed to see their alma mater getting a passing mention, or none at all. There’s simply not enough time in a ninety-minute film to cover every detail of HBCU life and history. This first full-length documentary, however, is one that HBCU alumni can be proud of, and one that any serious student of American higher education will want to screen. Tell Them We Are Rising shows that HBCUs are worthy of sustained support and attention because they continue to be important spaces for the cultivation of Black thought in America and globally.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

I look forward to viewing the documentary. I was at Fisk when Morris Brown failed, and we took insome it’s students and faculty. I have also served as a president of an HBCU. From your description, the film fails to provide a critique of how “well-meaning” boards of trustees, comprised of alumni—mostly Black me —, have stifled change at HBCUs. They keep a tight rein on Presidents and many hold positions for decades, which technically is illegal, but HBCUs fly under the radar screen. So as long as the casualties are us, and not white students, no one cares. White institutions did not cause the failure of Morris Brown. The tragedy is that rather than combine with other HBCUs in Atlanta. or simply fold, they try and persist, and for what? They have no accreditation, and the loser are the very few students who believe in them so much that they are willing to get a college education and receive a degree that is worthless.

There is no question in my mind that HBCUs served a unique and important purpose, and can continue to do so. But they need 21st C leadership in the presidents m,but most significantly on thei boards. There is a clear gender bias that suggesr HBCUs are a male-dominated club in terms of leadership and its Board members. yet over 50% of the students matriculating are black women. The Boards and Presidents of many HBCUs reflect an old boys network, except the “old boys” are black. But the same gender biases are present. You will find inequity between men and women faculty, and key administrative positions are generally occupied by men.

HBCUs never planned for the impact of desegregation on their enrollments, but there is no excuse for them not coming up with strategies to deal with changing student demongraphics over 50 years later. Poor leader (sometimes both corrupt and inept) in presidents and especially boards, fiscal mismanagement and a failure to identify what can HBCUs offer in the 21st C (and attract donors) are some of the causes of the demise of many of these illustrious institutions that stand as a lingering testaments to the resilience of Blacks as a people and as a culture that understood the significance of education.

The documentary didn’t go into great detail about the specifics behind Morris Brown. I’m looking forward to seeing it again to review what was covered. (There will be a Twitter chat about it during the film under the #HBCURising hashtag.) I know it was a complicated situation and I wish something could have been done to save MBC. And I share your concerns about the leadership at HBCUs. It’s well known that women are the majority of students in the AUC (and other HBCUs), and the faculty and administrations should better reflect that. Thank you for your insightful comments here.

Well done essay on HBCU’s . I attended Xavier University of Louisiana (69-79′) and it was a transformative experience. I need to emphasis something important here…we already have the infrastructure to raise us up to where we belong. There are over 100 HBCU’s with diversity of size, academic range and scope, endowments and student populations and there are many diverse faith institutions and communities as well. The faith community thru % of tides and potential students can adopt and/or partner with a HBCU of it’s choice. Other modes of resource exchange retired teachers, other professionals. The synthesis of combining something which was already there. Here we can develop communities, promote educational excellence and affirm faith churches and communities.

Financing HBCUs is a challenge, and the documentary does address some of the issues behind that. Thank you for reading the essay and adding to the conversation.