The Black Press and a Manly Vision for Racial Advancement

Upon leaving the Nation of Islam (NOI) in March of 1964, Malcolm X spoke publicly about what he called Elijah Muhammad’s “crisis in his own personal and moral life.” “He did not stand up as a man,” Malcolm said of the NOI leader, whose extramarital affairs and enormous financial gains had just been made public. Infuriated, the Nation used its periodical, Muhammad Speaks, to malign Malcolm as a “misguided brother,” “cowardly hypocritical dog” and a traitor. One of Malcolm’s former understudies and future NOI leader, Louis X, even declared, “Such a man as Malcolm is worthy of death.” Within months of this article’s publication – in a paper that he had founded himself – Malcolm would be assassinated.

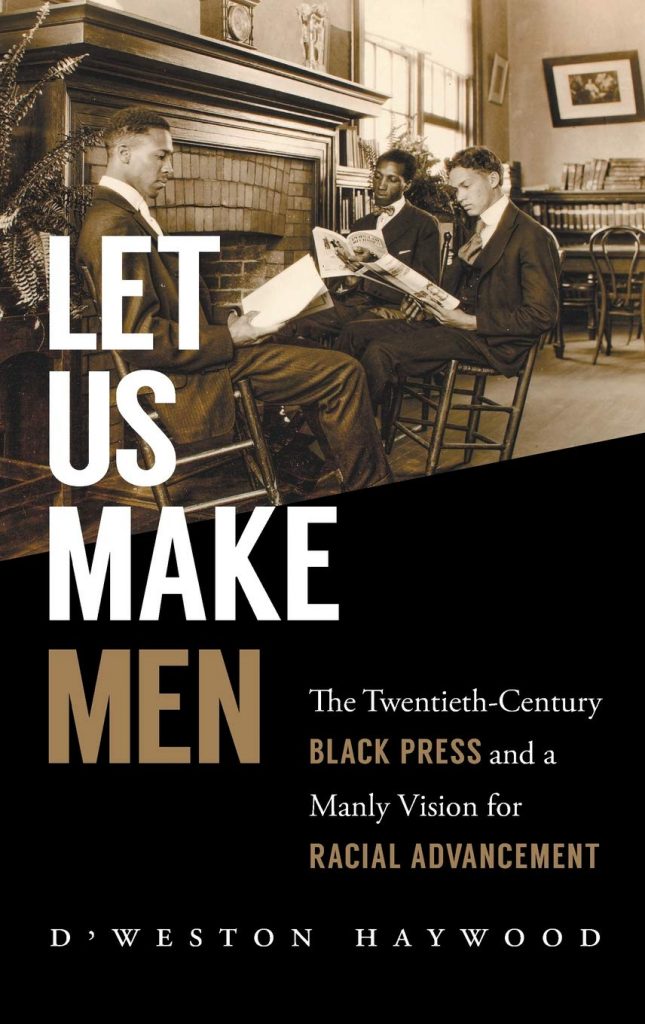

Far from an isolated case of using print media to espouse a competing vision, D’Weston Haywood’s Let Us Make Men: The Twentieth-Century Black Press and a Manly Vision for Racial Advancement brilliantly explores how men used the Black Press to contest each other’s leadership and expound their own “manly visions.” In Let Us Make Men, he explores how male publishers, editors, and activists used the Black Press to shape understandings of Black manhood and vie for leadership in the early- to mid-1900s.

The book begins with the founding of the NAACP’s Crisis in 1910 and Robert Abbott’s Chicago Defender in 1905. Weston maintains that during the first decades of the twentieth-century, “the press became the most vocal, visible, consistent, and influential proponent of black equality and race advancement” (23). He then moves through the infamous press wars between Crisis editor WEB Du Bois, and Marcus Garvey, the Pan-Africanist leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Relatedly, he examines the transfer in leadership (and masculine ideals) between Abbott and John Sengstacke, his successor at the Defender. The book also provides an important intervention in the historiography by exploring two largely unknown magazines published by Robert F. Williams (Crusader) and Malcolm X (Muhammad Speaks).

Haywood shows that throughout the Great Migration, the Black Press and the urban North were in a symbiotic state. Both the Defender and the Crisis struck pro-migration stances. Under DuBois’ leadership and within his “man of letters” (28) model of masculinity, the Crisis engaged with migration via the burgeoning study of sociology, of which Du Bois was a pioneer. Meanwhile, Abbott used his Defender to argue that migrating North, particularly to Chicago, “was not a cowardly retreat” (38). It constituted the fulfillment of manhood by abandoning a place (the rural South) that had long emasculated Black men and left them powerless to protect their wives and daughters. Indeed, Abbott opined in 1917, “[E]very man that has a spark of manhood or Race loyalty about him will join this national movement” (38). As such, the Defender helped to cement the notion that manhood entailed freedom of movement.

Such ideas about masculinity coincided with a crisis in Black male leadership, when “black male leaders were looking for an issue or a movement that would show their leadership and proper gender identities just as the Woman’s Era had done for black women” (38). Another such crisis occurred during the Great Depression, which saw “newspapermen” mobilize around the need to redeem Black manhood. Here again, the Defender took center stage as readers pondered the gendered implications of the “underutilized black male worker,” a concept that was as much a construction of the Black Press as it was a reality (99). The Defender’s readers reiterated this point, as when Reverend J.C. Austin wrote that public relief was emasculating: “Strong men find their joy now with a loaf of bread under their arms…This system cannot make man. We want to work!” (109).

However, Abbott’s nephew and successor, John Sengstacke, eventually took over the Defender and renewed the “self-made man” ideal (133). The “self-made man” model of masculinity was based on the more “cooperative” ethos that the Popular Front of the 1930s had embodied. By 1940, Sengstacke co-founded the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association, a “business organization, racial organization, and black fraternity” that brought together leading “newspapermen” to form a powerful, masculine voice of the Black Press (130). Founding the association meant that Sengstacke continued his uncle’s tradition of manly enterprise, yet revised it so that male collective endeavor, rather than individual pursuit, was prioritized.

Let Us Make Men concludes by illuminating how the Black Press was used in post-war freedom struggles, especially in helping men define their visions of manhood. Both chapters – one on Williams’ Crusader and the other on the NOI’s Muhammad Speaks – unveil how an ethos of “print and practice” (141) shaped not just the words that appeared in these radical papers, but the manly practices that also embodied the papers’ ideals. Williams, for instance, founded the Crusader shortly after the NAACP censured him in 1959. The paper worked as a refusal to retract his stance on armed self-defense. Meanwhile, NOI members dressed in their finest and aligned with the manly decorum dictated by the NOI as they sold Muhammad Speaks.

One of Haywood’s key contributions lies in his analysis of the post-war Black freedom struggle. He shows how the press was a vehicle for Black masculine expressions and debates, while providing a “voice” for various radical groups. Let Us Make Men encourages readers to think more carefully about the production side of the Black Press – the founding of periodicals, the selling of the papers, etc. The book also reviews how the Black Press spurred shifts in the framework of Black masculinities. For instance, it reveals that the mainstream Black Press sided with Martin Luther King, Jr., when his nonviolent “strong man” model was pitted against Williams’ armed self-defender and protector of family. Even while Williams ideals found widespread support amongst many Black activists, much of the Black Press defended King and nonviolence against emasculating accusations. As one 1959 Defender headline ran, “Non-Violence Shows Strength, Not Weakness” (162).

Though there is much to praise, Let Us Make Men portrays such maneuvers happening outside the influence of Black women. The introduction makes clear that constructions of Black manhood and womanhood were intertwined, and there are certainly places in which women are seen contributing to the Black Press or upholding some of the masculine ideals it set forth. Yet, they are conspicuous in their absence when it comes to assessing their impact on the “manly visions.” In what ways did women challenge these visions? Did they write to these editors and publishers? Did they produce pamphlets or newsletters of their own? Did such challenges re-shape in any way the pursuits of these visions?

As historian Kate Dossett argues, newspaperwomen like Amy Jacques Garvey sometimes used the press to hold men accountable for the masculine ideals they espoused, especially when they were not living up to them. The way that figures like Jacques Garvey challenged – and to be sure, supported – the “manly visions” of the Black Press is surely crucial for understanding how men and women (re)produced these concepts. Including Black women’s own visions, challenges and ideas about Black masculinities complicates and enriches our understanding of who invested in which “manly vision” and why.

Overall, Let Us Make Men clearly articulates how gender indelibly shapes racial justice and the Black Press’ historical role in advancing it. Readers will benefit from Haywood’s careful deconstructions of the complex, and at times, competing “manly visions” offered by Black newspapermen.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

I agree that Haywood does a masterful job of articulating his argument that African American newspaper publisher and editors used the press to establish a model of masculinity and that the model evolved and diverged over the course of the 20th century. In focusing his attention east of the Mississippi River, however, he misses the opportunity to exam whether the evolution of the ideas of black masculinity happened earlier or later west of the Mississippi. His use of quotes from Chester A. Franklin, Kansas City Call, indicate that he is very familiar with these Abbott and Sengstacke contemporaries.

Let Us Make Men was a thought-provoking read and I appreciate the introduction of Robert Williams and the Crusader. I’ll move Negroes with Guns up on my reading list.