Slavery, Family Separation, and the Ransom Case of John Weems

During the nineteenth century, several state laws prohibited, or restricted the ability of African Americans to testify against white people. As historian Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor has demonstrated in Colored Travelers: Mobility and the Fight for Citizenship Before the Civil War, these laws restricted the movement of Black people, making it more difficult for those who were enslaved as well as free. In some cases, the relative lack of legal rights emboldened slavers to extort free Blacks to sell them into slavery. The case of John Weems and his family is one of the most famous examples.

John and Arabella Weems lived in Montgomery County in Maryland. They were married in St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church on March 1, 1829, a formality unusual among enslaved people in the South. At the time of their marriage, John was a free man who had purchased his freedom prior to the wedding. His bride, Arabella, was an enslaved woman and her master, Adam Robb, had promised the couple that John could purchase his wife and their children at “a reasonable price.” Robb initially refrained from selling away Arabella or the children, even as he separated other enslaved families he owned. Biographer Bryan Prince found evidence that Robb’s treatment of the Weems family was motivated less by charitable disposition than by annual payments that Weems made to Robb to ensure that his family was kept together. But this informal arrangement had no protection under the law.

Like other states during this period, Maryland began to pass restrictive laws that were intended to discourage runaways. One such law passed in 1838 mandated the out-of-state sale of any attempted runaway by state auction. A year later, a law was passed that allowed for the enslavement of free Black men and women found not to have “visible means of financial support” or “good and industrial habits.” John Weems worked as a laborer on a small farm, but the couple’s growing family and the promise of purchasing their freedom meant that money was tight. Moreover, he lived in close proximity to Washington, D.C., which had its own set of restrictive laws. For example, free Blacks were required to carry a certificate of their free status. The initial cost of a certificate was two dollars, with an annual renewal fee of one dollar. These fees were prohibitive for many, and came with the additional challenge of finding five white men to vouch for one’s character. When Arabella’s owner eventually wavered on honoring his agreement to free the Weems family for a reasonable cost, the legal climate that stacked the deck against freedmen helped contribute to the Weems family’s plight. These laws were a boon to those who kidnapped freedmen for sale into the slave trade.

The family’s fortunes began to change in 1847 with the death of Adam Robb. According to his will, his slaves were divided between Robb’s daughters, Jane Robb Beall and Caroline Robb Harding. Arabella Weems, her daughter Ann Maria, and the other Weems siblings went to the Hardings, who were heavily in debt and immediately sold the Weems to Caroline and Charles Price. The rash of anti-Black legislation in Maryland and D.C. meant that John Weems had few if any legal remedies to challenge the Robb family heirs’ failure to honor the agreement he had with Adam Robb.

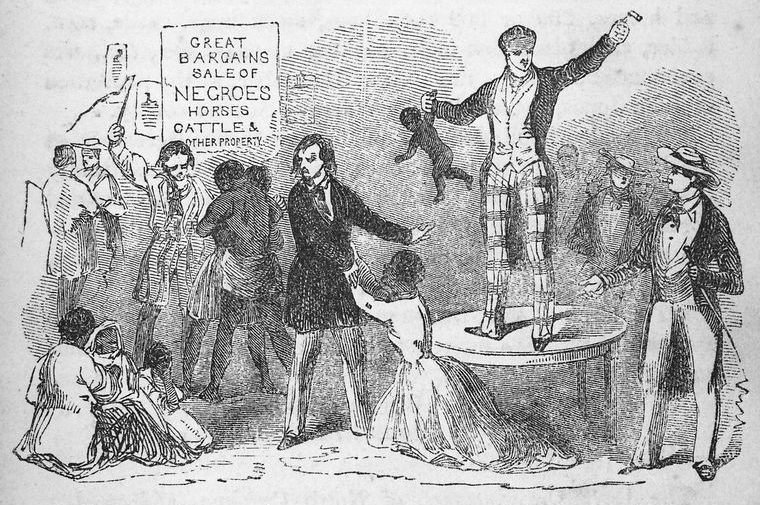

Ann Maria Weems, then 10 years old, was kept in the Price’s bedroom. They rejected a $700 offer for her. She ran away around 1852 at the age of 12, fearful that she would be used as a “slave breeder.” Her sister Stella had already run away a few years earlier. In the meantime, John Weems had fully expected to purchase what was left of his family, and made a trip to New York in order to make arrangements for their manumission. When he returned, he found that his wife and seven children had been relegated to a Washington, D.C. slave pen for sale. The price for their purchase had gone up exponentially from what was originally promised.1 The family had been sold to slave traders for $3300, and when John Weems returned he was offered his wife and youngest daughter for $900. Weems only had $600 and an offer by a local businessman to lend him $1700 if he could raise $1600 (approximately $52,400 in 2017) in matching funds quickly fell through as Weems only had a matter of days to raise the money.

The Weems family’s story quickly generated interest among abolitionists, notably Henry Highland Garnet, a prominent African American abolitionist and minister who had himself escaped from slavery in Maryland as a child. A pamphlet published in Scotland detailing the Weems’ plight was circulated in 1852. It describes Stella Weems as Garnet’s “adopted daughter.”2 While the pamphlet’s author was unattributed, the invocation of Garnet’s name makes it probable that he authored it, or at the very least had a significant hand in its publication and dissemination. The pamphlet notes that the New York Vigilance Committee for the Aid of Fugitive Slaves wrote to Garnet to indicate that they would “have to go.”3 The Committee appeared poised to help raise the funds and negotiate a release.

As was the case with most enslaved Black families, the Weems family was separated and sold among different plantations throughout the South. Working through the Underground Railroad network, and with the support of Garnet and his circle, John Weems continued to try to find and buy his family. He and his wife Arabella were eventually able to unite their family. Right before the Civil War, they moved to Canada where they spent the remainder of their days.

The story of John Weems highlights not only the pervasive problem of family separation, but the challenges that free people of color faced as newer Black Codes were enacted at state and federal levels. While Robb, the man who enslaved Weems’s family, might have honored their agreement if John Weems had raised sufficient funds during Robb’s lifetime, neither Weems, nor his family would have had any recourse had he not. That Robb specifically willed Arabella and her children to his daughter suggests that he’d made an agreement with Weems that he never expected to honor. These developments underscore how both enslaved and free Black people in the antebellum U.S. were subject to the whims of enslavers.

What a powerful story. Thanks. Dr. Parr. A descendant of John & Arabella Weems lives in Buxton, Ont., Canada. Mr. Bryan Prince is the author of ‘I Came as a Stranger: The Underground Railroad’ and ‘A Shadow on the Household.’ John Weems was a great man whose experience, together with that of his family, must never be forgotten.

James Oloo

@JamesAlanOLOO

I just found out that I am a descendant of John and Arabella Weems