Frederick Douglass and Fugitivity

*This post is part of our online forum on the life of Frederick Douglass.

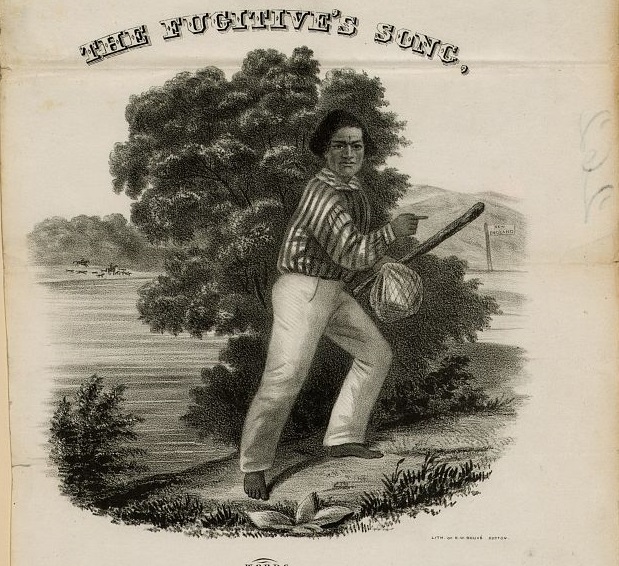

If I had to choose a single word to describe the life and politics of Frederick Douglass, I would choose “fugitivity.” Douglass’s fugitivity did not just give him an experiential view of slavery, an idea that many historians find compelling when describing Black abolitionism, but an epistemological standpoint that served as the best intellectual and polemical riposte to the proslavery argument. Douglass’s storied career as a fugitive slave abolitionist also personifies a more capacious understanding of slave resistance. Not merely as in overt acts of resistance and rebellion that were few and far between but in a continuum that would include runaway or self-emancipated slaves, the production of slave narratives or what I call the “movement literature” of abolition, and the use of law and politics as instruments of liberation.

Even at an individual level, for Douglass the struggle over fugitivity and national belonging was both a life-long personal and political project. It was the double consciousness that W.E.B. Du Bois wrote about evocatively in The Souls of Black Folk (1903), “The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife—this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self.”

In his eulogy for Douglass, delivered on March, 1895 soon after his death, Du Bois noted Douglass’s transformation from a fugitive slave abolitionist to an American statesman, one who like Abraham Lincoln, William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, and Charles Sumner was a builder of the antislavery state. Du Bois called him “our Moses.” And indeed Douglass was a Moses not so much in the conventional sense as just a leader of his people but as one who searches for national belonging. Douglass’s fugitivity, in this sense, in but not of the American nation, would haunt him throughout his long life, long after the fugitive slave had become an icon of Black statesmanship.

In the two decades before the Civil War, a new generation of African American abolitionists, most of them fugitive slaves, dominated the abolition movement. Of these what I call fugitive slave abolitionists, Douglass was, of course, the most famous. The trajectory of his uniquely triumphant abolitionist career illustrates how self-emancipated slaves came to lead the movement. On February 24, 1844, the Liberator printed an admiring report on Douglass’s “masterly and impressive” speech in Concord, New Hampshire. Douglass, the writer fantasized, was like “Toussaint among the plantations of Haiti. . . . He was an insurgent slave, taking hold of the right of speech, and charging on his tyrants the bondage of his race.” The fugitive slave was the master of his audience.

The story of Douglass’s escape to freedom has been told many times, starting with Douglass himself who wrote three iterations of his autobiography. I am less concerned with the details of his well-known life-story here than with the sense of fugitivity that would haunt both his abolitionist and later political career as a Radical Republican.

A Black abolitionist underground network that stretched from the free Black community in Baltimore, to which his wife Anna Murray belonged, to the more organized abolitionist vigilance committees in New York City that included prominent Black abolitionists such as David Ruggles and James W.C. Pennington, made possible his escape from slavery. The interracial abolitionist community in New Bedford, Massachusetts made him an avid reader of William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator. Discovered by abolitionists for his talent and efficacy as a speaker, Douglass soon became known for his extraordinary lectures on his experiences in slavery and remarkable escape.

One of the most effective lecturing agents of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, Douglass’s speeches were an abolitionist sensation, because of his unique perspective, his fugitivity. “My back is scarred by the lash—that I could show you. I would I could make visible the wounds of this system upon my soul,” he said in one of his early speeches. After his break with Garrison in the 1850s, Douglass recalled that he had been asked simply to tell his story, but he actually developed a wide-ranging repertoire that indicted southern slavery, northern racism, and the government, and lampooned proslavery Christianity. It was not simply the numbers of fugitive slaves escaping to free territory but the effective political and ideological warfare carried on by fugitive slave abolitionists like “the black Douglas [sic],” that made slaveholders nervous and southern secession conventions draw attention to fugitivity in their declarations and ordinances of secession.

Fugitivity also embodied the vulnerability and precarity of Black freedom. Indeed, all was not accolades, as Douglass broke his right hand in a fracas in Indiana, endured the abolitionist baptism of being pelted with stones and rotten eggs, and was subjected to racist aspersions that he could not possibly have been a slave. It was to answer these suspicions and to capitalize on the popularity of his lectures that Douglass published his best-selling slave narrative in 1845, to rave reviews. To Douglass’s iconic narrative belongs the credit for making the slave’s indictment of slavery the most effective weapon in the abolitionist arsenal and for popularizing the genre. It was as William Andrews has put it, “the great enabling text of the first century of Afro-American autobiography” the fugitive slave narratives. Douglass’s narrative’s extraordinary success had made him an instant celebrity. Since he had revealed his identity and that of his erstwhile masters, however, he was in danger of re-enslavement.

Fugitivity followed Douglass abroad. On Garrison’s advice, Douglass embarked on a lecture tour of the British Isles, where he pointedly noted that he was “an outlaw in the land of my birth.” In fact, Douglass’s star turn in Ireland and Britain made fugitive slave abolitionism an international sensation. In one of his first speeches in Dublin, he stated, “I am the representative of three million bleeding slaves.” At events featuring other speakers, Garrison reported that Douglass was the lion of all occasions. Douglass gave more speeches during his eighteen-month tour than any other American abolitionist. In England he emerged as a bona fide abolitionist leader. But Douglass’s fame put his freedom in jeopardy. In Britain the abolitionist Quakers Anne and Ellen Richardson raised more than sufficient money to purchase his freedom. Numerous American fugitive slaves had purchased their freedom with British assistance. Douglass, however, was no ordinary fugitive but a leading light of the movement, and his self-purchase aroused considerable controversy.

When abolitionist newspapers expressed discomfort at a deal that seemed to recognize property in man, Garrison leapt to Douglass’s defense, calling it “The Ransom of Douglass.” Abolitionists, he wrote, were against compensating slaveholders as a “class” for emancipation, but they had always helped ransom individual slaves, conveying the illegitimacy of slaveholding as kidnapping. Few of Douglass’s critics, he continued, endangered their own freedom in the manner that they demanded of fugitive slave abolitionists.

Douglass raised sufficient funds in Britain to start publishing the North Star in Rochester in 1847, dedicated to his “oppressed countrymen.” Its very title was resonant of fugitive slave abolitionism despite his legally bought freedom. Fugitivity also defined Douglass’s break with Garrison in 1851, when he became a political abolitionist. In an essentially ideological fight with personal overtones, Douglass accused Garrison of racial paternalism and Garrison used Douglass’s fugitivity against him. We often think of Garrison’s allusion to Douglass’s relationship with British abolitionist Julia Griffiths as his most stinging criticism, but it was Garrison’s claim that fugitive slaves like Douglass had no special insight into abolition that really got to Douglass.

Throughout the 1850s, fugitivity and a yearning for national belonging, marked Douglass’s ideas or as David Blight put it in his first book, Frederick Douglass’ Civil War, he swung like a pendulum between hope and despair. As a political abolitionist, one who pointed to the antislavery nature of the US Constitution, Douglass, the former slave, laid claim to the American state. But on the eve of the Civil War, he briefly contemplated migration to the one Black nation in the Western Hemisphere, Haiti.

Fugitivity and the struggle for belonging also shaped Douglass’s most famous abolitionist speeches, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” (1852) and the lesser known “A Nation in the Midst of a Nation” (1853). The history of Black people in the United States, he said using the Irish nationalist Daniel O’Connell’s allusion, may be traced like the blood of a wounded man in a crowd. African Americans were treated like aliens in the land of their birth. White Americans had sympathy for “the Hungarian, the Italian, the Irishman, the Jew, and the Gentile….but for my poor people enslaved—blasted and ruined—it would appear that America has neither justice, mercy, nor religion.”

The search for belonging would continue to shape Douglass’s later career, his demand for suffrage and the rights of American citizenship and determination to establish an interracial democracy in the United States during Reconstruction. Of course, he lived long enough to see all the gains of war whittled away by racial terror and in law. One of Douglass’s last speeches was on the new “Southern Barbarism” of lynching and the criminalization of blackness in the Jim Crow south. Fugitivity under slavery had been transmuted to criminality in freedom. As Douglass put it, “It was to blast and ruin the negro’s character as a man and a citizen.” African Americans continued to be read out of the bonds of citizenship and the protection of the law.

Fugitivity bookends not only Douglass’s life but also the history of Black slavery and Black freedom. Even as African Americans laid claim to nativity and citizenship, enshrined in the Reconstruction laws and constitutional amendments, racial terror, legal mechanisms, racist mores, custom, and practice stole from them the rights and privileges of American citizenship, consigning them out of the national body politic. When Douglass died, the shadow of slavery, fugitivity, hung heavy over Black people, for slavery refused to be fully conquered, transmuting into states historians have variously called the nadir, slavery by another name, worse than slavery, Jim Crow, the new Jim Crow, racial capitalism, and mass incarceration. The irony of the most photographed and apparently most heard American of the nineteenth century representing the most disfranchised and oppressed section of the American nation state is embedded in the history of the Black protest tradition that Douglass exemplified. As for Douglass, fugitivity, remains a powerful site for Black intellectual and political critique in the twenty first century, never a simple, liberal plea for inclusion but a radical demand to reimagine and remake American democracy.

*This post was originally delivered as an address in the plenary of the Frederick Douglass in Paris Conference in October 2018.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.