Black Mobility, Law, and Freedom

In 1849, an unnamed Missouri slave owner took a male slave to California to search for gold. Two years later, as the enslaved and the slaveholder were headed back to Missouri, someone they met en route learned that they had been in California for two years and advised the slave that by the laws of California he was free. The slave sued both for his freedom and for back wages from his owner, who had become quite rich. The full details of the case were not reported, but it received mention in The National Era, an African American newspaper based in Washington, DC.

Similarly, in the late 1840s, the city of Worcester, Massachusetts was captivated by a case of an enslaved Black woman who was suing for her freedom. She had been brought to Massachusetts from the South. As the work of Nikki Taylor, Katherine McKittrick, Charmaine Nelson, and others have shown, legal geography—the co-mingling of spatial and social elements—was a critical element in slavery and freedom. The details of her case are sparse, although her mistress claims that she was not a slave, but a servant. It was a dubious claim, since the plaintiff appeared unable to walk away of her own accord. Moreover, the term “servant” was a common euphemism used both in the South and in New England to whitewash slavery.

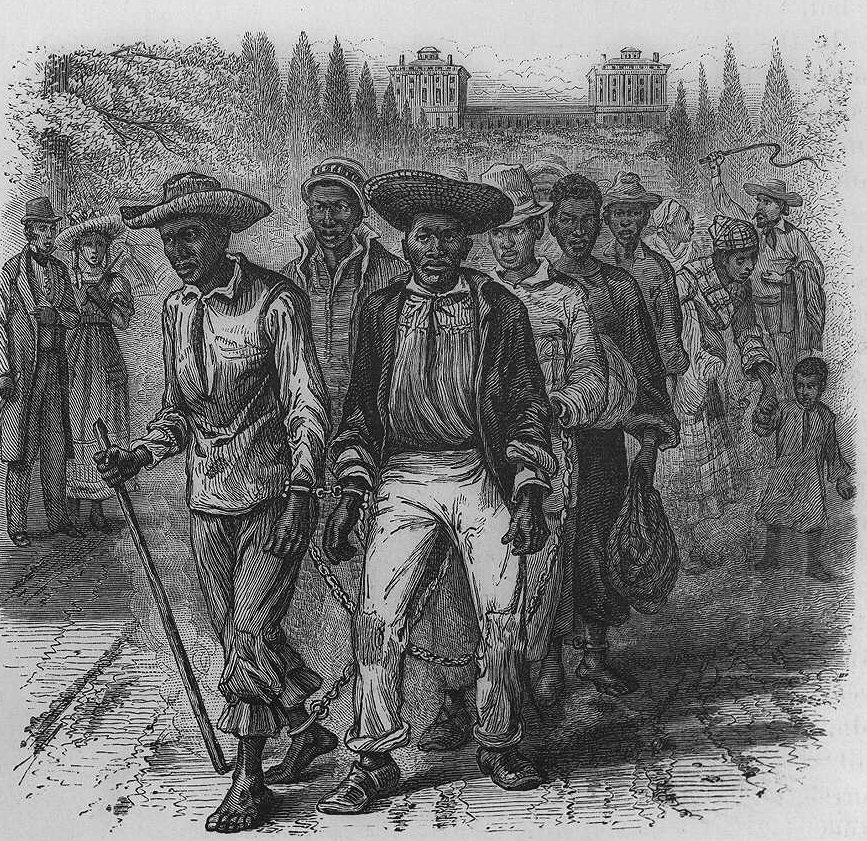

While no land in the British Atlantic was truly free of oppression, location sometimes offered the enslaved the legal standing to challenge their enslaved condition. These cases were predicated on a mixture of property and labor law as well as laws specifically designed to deny personhood, citizenship, and mobility to Black bodies. In particular, there was a longstanding provision under writs of habeas corpus to challenge illegal detainment. Habeas corpus drew from English law, evolved over centuries, and codified in the 1640 and 1679 Acts of Habeas Corpus. It was successfully used in 1772 in the Somerset Case, in which James Somerset sued his former master on the grounds that he was being illegally detained; slavery was legal elsewhere in the British Empire, but not in Britain itself. From the 1770s onward, members of the Clapham Sect used habeas corpus writs to challenge a number of kidnappings of Black Britons. As a byproduct of English law, writs were also used in American jurisprudence to challenge the enslavement of a number of individuals.

The enslaved man from Missouri had grounds to sue because he had been brought to California, a non-slaveholding state. In the case of the second plaintiff, she used the occasion of having been brought to Massachusetts to challenge her bondage. Notably, both cases fell before the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. While the plaintiff in the Massachusetts case insisted that she was no fugitive, legal challenges like hers were complicated by laws intended to undermine the northern states’ status as a safe zone for those who managed to escape their enslavement.

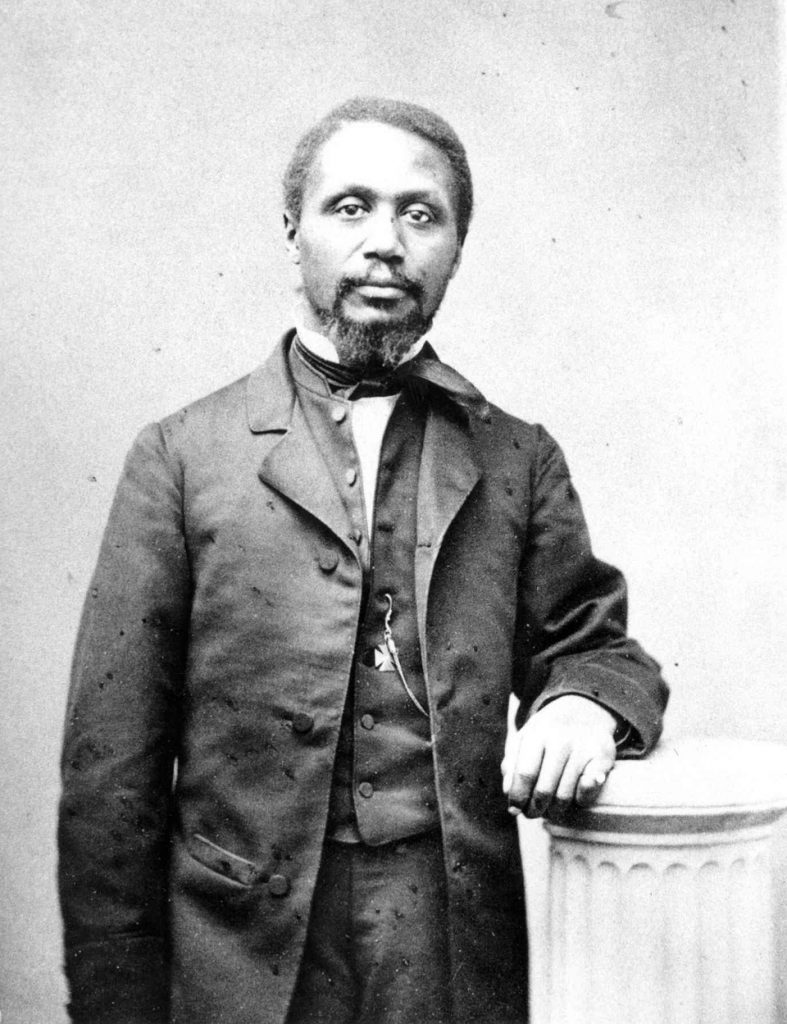

What is significant about these two cases, separated by time and geography, is that they are two examples from a number that were documented by the free Black community, with a particular attention to location. Stories about these cases appeared in snippets in both Black and white newspapers. The first case of the enslaved man from Missouri appeared in an African American newspaper after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act. The Massachusetts plaintiff’s case was documented via news clippings, collected by Robert Morris, a prominent African American attorney from Boston who had ties to Boston’s abolitionist community and was a member of the Prince Hall Freemasonry Lodge. Morris made a career of civil rights cases. He was the first to challenge school segregation—in 1848—and represented Anthony Burns, Shadrach Minkins, and the Massasoit Guards in cases involving the Fugitive Slave Act. The Massasoit Guards were an African American militia founded specifically to defend Black Bostonians and runaway slaves against slave catchers.

Legal challenges to slavery were a source of hope for abolitionists. It is hardly surprising that a prominent Black attorney would take an interest in such efforts. The Black abolitionist community was forced to contend with a white legal system. This documentation of cases involving challenges to slavery should be understood as examples of the production of Black legal knowledge. Morris was exceptional, even among African-Americans who overcame considerable racial barriers to become attorneys in the first place.

Yet, as Stephen Hall demonstrates, the dissemination and collection of these cases in Black print culture, and by Black attorneys can be construed as representing more than hope for emancipation. Rather, it can be understood as a collective action to assemble a Black legal cartography. In her study of Black women’s cartographies of freedom, McKittrick has meticulously demonstrated the importance of “space, place, and location” in considering how Black women experienced their struggles. In negotiating experiences that encompassed slavery, violence, and sometimes freedom, human geography mattered. And, in considerations of slavery, it was a frequently-changing human geography that shifted on local, national, and imperial scales. When considering the human geographies alongside the relevant legal geographies, Black anti-slavery activists faced a moving target that needed to be challenged at multiple levels. The documentation, dissemination, and collection of legal precedents inside and outside the antebellum Black legal community served as a means for the diaspora to track these shifting legal geographies, these tenuous domains of freedom.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.