“Class Struggle Pan-Africanism”: C.L.R. James in Imperial Britain

In her contribution to the 1992 edited volume C.L.R. James’s Caribbean, the Jamaican literary scholar Sylvia Wynter coined the term “Jamesian poiesis” to explain how C.L.R. James worked through the multiple contradictions that marked his intellectual and political lives. James was “attached to the cause of the proletariat, yet a member of the middle class, a Marxian yet a Puritan,…of African descent yet Western, a Trotskyist and Pan-Africanist.” This set of apparently incompatible cultural and political orientations led James to eschew “either/or” frames of analysis or modes of political action (race, class, “Pan-African nationalism or labour internationalism”) in favour of a “counterdoctrine” in which “multiple modes of domination” are “nondogmatically integrated” in a way that challenges both “the basic categories of colonial liberalism” and the “labour-centric categories of orthodox Marxism.”1

As a scholar, C.L.R. James made critical contributions to Pan-African, anti-racist, anti-colonialist and Marxist thought, and his writing on cricket was an important precursor to the development of the discipline of cultural studies. As an activist, he was a central figure in labour and Pan-African movements from the interwar years through the Black Power era. As Wynter argues, James was an “exceedingly complex and subtle thinker” whose work defies easy categorization and challenges scholars to—at the risk of repeating a well-worn cliche—go “beyond boundaries” in order to grasp its intellectual richness. In his 2014 book C.L.R. James in Imperial Britain, Christian Høgsbjerg traces how, in six years living in Great Britain (1932-1938), the Trinidadian novelist, historian, cricket writer, political philosopher and activist transformed himself—from an aspiring writer whose analysis of the relationship between the colonial West Indies and the metropole focused on advocating for Dominion status for the islands—into one of the leading lights of twentieth-century political radicalism in both Marxist and Pan-African traditions.

Høgsbjerg sets out to remedy an important shortcoming in studies of James while chronicling a key, and remarkably understudied, period in the life of one of the twentieth century’s greatest minds. In the six and a half years he spent in Great Britain, James wrote a number of key texts addressing contemporary and historical struggles against racism and imperialism (The Case for West Indian Self-Government, A History of Negro Revolt, The Black Jacobins, and a play about Toussaint Louverture that starred Paul Robeson), produced two historical studies about the history of communist politics (writing World Revolution, a history of the Communist International and translating Boris Souvarine’s biography of Stalin), ghost-wrote West Indian cricket great Learie Constantine’s autobiography, covered cricket for the Manchester Guardian and the Glasgow Herald and published the first novel by a West Indian living in Britain. He also played prominent roles as an organizer, speaker, writer and editor with a number of groups focused on the fight against colonialism including the League of Coloured Peoples, the International African Friends of Abyssinia, the International African Service Bureau and socialist/Marxist organizations like the Independent Labour Party and the Fourth International.

The wide scope of James’s achievements contributes to what Høgsbjerg sees as a serious flaw in how academics understand the man and his work. Contemporary scholarship, reflecting postmodernist tendencies, “remains set against any attempt to see James’s life’s work as a coherent totality beyond a slightly abstract sense” in favour of what the American labour activist Martin Glaberman saw as a “fracturing” of James into discrete categories that robs us of a unified analysis of James’s intellectual production and political work. This inability to properly frame James’s oeuvre is not only a scholarly concern, it has political effects. As scholars paint an image of James that focuses on the literary and cultural dimensions of his work, we lose a sense of how those aspects were part of a larger project, the ultimate goal of which was “socialist revolution and anti-imperialist revolt,” a set of causes that Høgsbjerg muses that “no postmodern academic today would even dare to ‘imagining,’ let alone commit themselves to agitating for.”

The wide scope of James’s achievements contributes to what Høgsbjerg sees as a serious flaw in how academics understand the man and his work. Contemporary scholarship, reflecting postmodernist tendencies, “remains set against any attempt to see James’s life’s work as a coherent totality beyond a slightly abstract sense” in favour of what the American labour activist Martin Glaberman saw as a “fracturing” of James into discrete categories that robs us of a unified analysis of James’s intellectual production and political work. This inability to properly frame James’s oeuvre is not only a scholarly concern, it has political effects. As scholars paint an image of James that focuses on the literary and cultural dimensions of his work, we lose a sense of how those aspects were part of a larger project, the ultimate goal of which was “socialist revolution and anti-imperialist revolt,” a set of causes that Høgsbjerg muses that “no postmodern academic today would even dare to ‘imagining,’ let alone commit themselves to agitating for.”

C.L.R. James in Imperial Britain represents intellectual history at its best. Høgsbjerg reads James closely to show how his ideas about revolution, freedom and inequality emerged in dialogue with historical and contemporary political thinkers. Moreover, he sets James’s intellectual and political development in terms of how they were shaped by local and global dynamics.

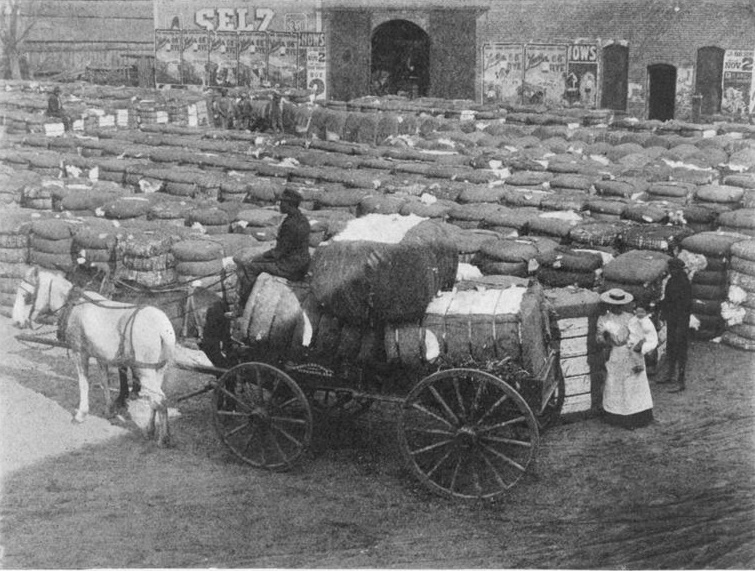

Of particular interest in tracing how local dynamics influenced James’s political development is Chapter Two, “Red Nelson,” which recounts the ten months that James spent in the Lancashire cotton town as Learie Constantine’s guest following his initial arrival in London. While Nelson was where James first encountered the work of Leon Trotsky, Høgsbjerg draws the reader’s attention to how James’s encounter with “the living tradition of socialism and class struggle” in this mill town played an important role in his radicalization. Local histories of popular resistance to capitalism “directly challenged James’s moralistic and Fabian vision of social change from above” and helped lay the groundwork for his vision of a radical politics grounded in the ideas and activities of the popular masses.

While James was profoundly influenced by the democratic political culture he encountered in Nelson, his political orientation at the time was largely directed towards the question of West Indian self-government, and while his public speaking on the topic resonated with audiences in Nelson, it was his return to London, and his immersion in a cosmopolitan network of anti-colonial activists that allowed him to become a thinker and activist who “advanced[d] and develop[ed] a Marxist perspective on black and colonial liberation struggles across the African diaspora.”

In recent years, scholars like Kennetta Hammond Perry, Marc Matera, Minkah Makalani, and Hakim Adi have documented the transnational social and political networks that made London of the 1930s a key site for the development of Black internationalism and anti-colonial politics. Høgsbjerg’s analysis sets the contributions of one of those movements’ key figures in a broad international context, showing how global events such as the rise of fascism and Nazism, the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, and the Soviet Union’s and the Communist International’s response to profound changes in international politics helped to shape what Kent Worcester calls James’s “class struggle Pan-Africanism.” Of particular note to students of James’s thought is Høgsbjerg’s demonstration of how James’s London years represented a time when his anti-colonial thought expanded from the specific situation of the West Indies to encompass ideas about the political and creative capacities “of African people as a whole,” an idea that was central to The Black Jacobins, a book that, while about the Haitian revolution, was influenced by James’s vision of an “African revolution” that could be made possible by a looming conflict in Europe.

C.L.R. James in Imperial Britain tells the story of a critical period in James’s life and shows us how his Pan-African and Marxist orientations fed each other and coalesced into a unified vision of revolutionary freedom. The book is a valuable contribution to an expanding body of scholarship on twentieth-century Black transnationalism. More to the point, Høgsbjerg has shown himself to be not only an important historian of James. With his call to read James as a way to inform the continued development of a revolutionary politics of freedom, he reveals himself to be working in a Jamesian mode of engaged scholarship, something that is as important to our troubled times as it was to James’s.

- Sylvia Wynter, “Beyond the Categories of the Master Conception: The Counterdoctrine of the Jamesian Poesis.” In C.L.R. James’s Caribbean, ed. Paget Henry and Paul Buhle, 63–91. Durham: Duke University Press, 1992. ↩

Readers may also be interested in this title (co-edited by Høgsbjerg), recently released: Forsdick, Charles and Christian Høgsbjerg, eds. The Black Jacobins Reader. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017.

Thanks for reading, and for the heads-up. I’m waiting for my copy, and will probably be reviewing it in this space soon.