Abeng and Black Power in the West Indies

My interest in Black Power and post-war Black radicalism more generally grew not out of an initial interest in African-American manifestations of those movements, but through how they unfolded in the West Indies and in my home country of Canada, where a generation of expatriate West Indians were actively involved in the development of new approaches to anti-racist and anti-imperialist thought and action. A chance encounter in 2005 with David Austin’s masterful three-part CBC radio documentary on the Trinidadian Marxist pan-Africanist scholar and activist C.L.R. James drew me into the compelling history of Caribbean radical thought. I began reading the works of James and his contemporaries, following the thread to 1960s-era activist intellectuals like George Beckford, Lloyd Best, Norman Girvan, and Walter Rodney, and to events such as the “Rodney Riots” and the 1970 Black Power uprising in Trinidad and Tobago. It was only after immersing myself in these histories that I began to learn about the work of the African-American thinkers and activists who played a role in influencing the development of West Indian radicalism in the 1960s and 70s.

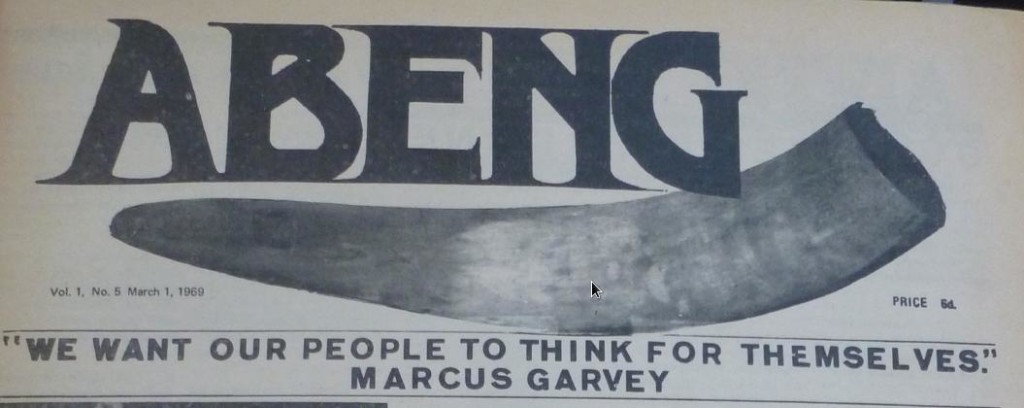

I also have a strong interest in the history of print culture and the role that newspapers play in the development and spread of new types of critique and inquiry. In this first blog post, I will briefly discuss Black Power in the West Indies and address how that movement found expression in one newspaper, Abeng, a Jamaican publication that existed for only nine months but was a major force in the development of Jamaican and Caribbean radical thought.

Increasingly, scholars are talking about Black Power as an inherently transnational movement. Nico Slate writes that Black Power’s “global history” reveals the “many interwoven, at times fraught, and often surprising relationships between Black Power activists and their ideas throughout the world.” Seeing Black Power through a global lens draws attention to the “interconnectedness across difference” shared by thinkers and activists from Africa and its diaspora, revealing how Black Power movements “offered new forms of unity and collaboration … for a range of oppressed people throughout the world,” but were simultaneously rooted in particular local dynamics.1 Historians need to think about how Black Power activists in diverse locales shared ideas and approaches without losing sight of the distinctly local factors that shaped their work and not see any one instance of Black Power as an echo of another: as Anthony Bogues points out, to “ascribe authenticity to one conception of Black Power over another is to mistakenly privilege one African or diasporic site over another.”2

Reading the work produced by various West Indian Black Power movements reveals the multifaceted nature of Black Power. The growing radicalism of the African-American freedom struggle provided inspiration and influence to young West Indians, but, as Rupert Lewis writes, while West Indians were influenced by developments in the United States, they were “quite independent of them.”3 West Indians formulating new approaches to the struggle against racism and imperialism drew on ideas put forth by African-American activists like Amiri Baraka, Huey Newton, Angela Davis, Bobby Seale, and Stokely Carmichael (whose life, of course, draws attention to the role of West Indians in shaping Black Power in the United States, something I will address in a later post), but their work was deeply rooted in their own long history of resistance to racist and imperialist oppression. West Indian Black Power thinkers evoked such moments as the Haitian Revolution and the Morant Bay Rebellion as historical touchstones in the struggle for Black freedom, and drew on a rich body of Caribbean thought, including the work of Marcus Garvey, Eric Williams (whose critiques of racist imperialism were central to a movement that was also often critical of his political rule) and, perhaps most importantly, C.L.R. James, who, in the middle part of the 1960s developed close relationships with young Caribbean activists and thinkers, notably in study circles that brought him into regular contact with expatriate West Indians while he was living in the United Kingdom and Canada. 4

As West Indian Black Power movements were rooted in the region’s long history of resistance, they took shape in reaction to contemporary local issues. Anthony Bogues sees Jamaica’s expression of Black Power as a moment when, as earlier in the century with the emergence of Garveyism and Rastafari and during the 1938 labour uprisings, Jamaicans embraced “a politics of radical blackness” and brought “new political questions” to the forefront of public discourse.5 Foremost among these questions was the strong dissatisfaction felt by young West Indians towards the first generation of post-independence political leadership. To many young activists and political thinkers facing persistent unemployment and poverty and the continued marginalization of Black identity, the nationalists who had led Jamaica to independence were, in the words of Walter Rodney, agents of “white and racist-oriented” “metropolitan-imperial interests,” who had only “intensified the oppression” of the dispossessed Black masses.6

What Rodney was writing about – neoimperialist economic extraction from the decolonized world on the part of the United States, Britain, and Canada, the local leaders who fostered neoimperialist relationships with metropolitan nations, and persistent racism – were central themes of Abeng, a Jamaican newspaper that, as Rupert Lewis describes, emerged in “response to (Norman) Manley’s, (Alexander) Bustamente’s and (Hugh) Shearer’s maltreatment of the Rastafarian and Black Power movements.”7 The historian Ken Post (who wrote for Abeng under two different pseudonyms, “Omo Ogun” and “Historian”) sees Abeng as the product of a desire on the part of young Jamaican intellectuals and activists to give the widespread dissatisfaction felt by “younger people who’d been attracted by the message of Blackness and nationhood” “a political form.”8

Abeng had a short run, beginning publication in February 1969 and folding in November of that year after the presses where it was printed were destroyed in a fire (the collective that produced the newspaper survived into the 1970s and continued to publish pamphlets on various topics). Yet while it did not survive long, Abeng provides historians with a rich body of writing through which to trace the development of West Indian radicalism at a key juncture, namely the months after the “Rodney riots,” unrest that broke out in Kingston in October 1968 after Jamaica expelled Walter Rodney; the protests that followed Rodney’s ban were arguably the event that brought a locally-inspired Black Power movement into widespread public consciousness in Jamaica and the broader Anglophone Caribbean. This was a moment when West Indian intellectuals were formulating broad-based critiques of the postcolonial society that reflected the concerns of the popular masses and were intended to form the basis for political action, and, as Robert Hill writes, Abeng was a forum for the development of bottom-up critiques of the postcolonial state that had popular self-determination, as opposed to decolonization, as their focal point.9 The paper featured the work of many writers who are central figures in Caribbean radical intellectual history, including Hill, Rupert Lewis, George Beckford and Walter Rodney.

The desire of young Jamaican activists to tie their struggle to the Jamaican people’s long history of resistance can be seen, among other things, in the title of the newspaper – the abeng was a horn used by the Maroons to communicate between communities – as well as in the paper’s regular reprinting of Marcus Garvey’s writings. Abeng used these histories as a way to frame discussion of the continuing marginalization, oppression, and poverty suffered by Black people. The paper featured articles about Black struggles around the world, notably in Africa, but was largely focused on developments in Jamaica. Abeng consistently attacked neocolonialism for undermining Jamaican and West Indian political and economic sovereignty and was solidly critical of Jamaica’s ruling classes and of the ways in which economic activities such as tourism and bauxite mining served to extract wealth from Jamaica for the benefit of the interests of Britain, the U.S., and Canada.

Besides the scholarly writers listed above, Abeng also gave the Rastfari movement a forum in which to express its critiques of Jamaican politics; the centrality of Garvey and Rastafari to Jamaican Black Power discourse is a prime illustration of how Black Power movements need to be understood in terms of their own intellectual genealogies.

The complete run of Abeng is available online at the Digital Library of the Caribbean, making it a fantastic resource for students looking for easily-accessible primary material for an undergraduate honors thesis or graduate seminar paper on West Indian radical thought or Black Power in the Caribbean. My next blog post will address the paper’s circulation and readership.

- Nico Slate, “Introduction: The Borders of Black Power,” in Black Power beyond Borders: The Global Dimensions of the Black Power Movement, ed. Nico Slate (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 1–10. ↩

- Anthony Bogues, “The Abeng Newspaper and the Radical Politics of Postcolonial Blackness,” in Black Power in the Caribbean, ed. Kate Quinn (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2014), 80. ↩

- Rupert Lewis, “Learning to Blow the Abeng: A Critical Look at Anti-Establishment Movements of the 1960s and 1970s,” Small Axe, no. 1 (February 1997): 7. ↩

- David Austin, Fear of a Black Nation: Race, Sex, and Security in Sixties Montreal (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2013); C.L.R. James, You Don’t Play With Revolution: The Montreal Lectures of C.L.R. James, ed. David Austin (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2009); On James and the development of 1060s West Indian radical thought, see: Paul Buhle, Tim Hector: A Caribbean Radical’s Story (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2006). ↩

- Bogues, “The Abeng Newspaper and the Radical Politics of Postcolonial Blackness,” 79–80. ↩

- Walter Rodney, The Groundings with My Brothers (London: Bogle-L’Ouverture Press, 1996), 12. ↩

- Lewis, “Learning to Blow the Abeng: A Critical Look at Anti-Establishment Movements of the 1960s and 1970s,” 7. ↩

- David Scott, “Interview: ‘No Saviour from on High’: An Interview with Ken Post,” Small Axe, September 1998, 105–106. ↩

- Robert Hill, “From New World to Abeng : George Beckford and the Horn of Black Power in Jamaica, 1968-1970,” Small Axe 11, no. 3 (October 2007): 13–14. ↩