Black Britons and the Politics of Belonging: An Interview with Kennetta Hammond Perry

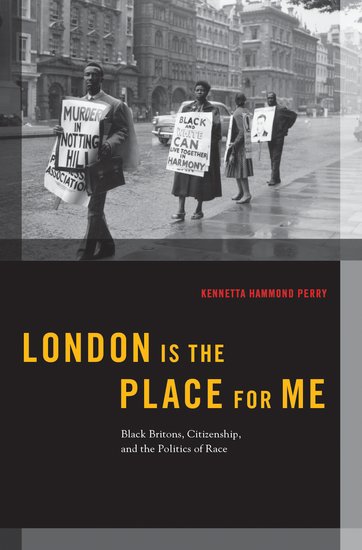

This month, I interviewed Kennetta Hammond Perry about her new book, London is the Place for Me: Black Britons, Citizenship and the Politics of Race (Oxford University Press, 2015). The book is part of the interdisciplinary series, Transgressing Boundaries: Studies in Black Politics and Black Communities, co-edited by Cathy Cohen and Fredrick Harris. Situating the post-World War II mass migration of Afro-Caribbeans to Britain in the context of transatlantic political movements for citizenship and self-determination, Perry chronicles how migrants “reconfigured the boundaries of what it meant to be both Black and British” while living and working in the imperial metropolis. Unwilling to accept second-class citizenship, Afro-Caribbean migrants formed grassroots organizations to protest racial discrimination, lobbied for legal reform, and repurposed popular Caribbean festivals to secure to their rights as British citizens.

This month, I interviewed Kennetta Hammond Perry about her new book, London is the Place for Me: Black Britons, Citizenship and the Politics of Race (Oxford University Press, 2015). The book is part of the interdisciplinary series, Transgressing Boundaries: Studies in Black Politics and Black Communities, co-edited by Cathy Cohen and Fredrick Harris. Situating the post-World War II mass migration of Afro-Caribbeans to Britain in the context of transatlantic political movements for citizenship and self-determination, Perry chronicles how migrants “reconfigured the boundaries of what it meant to be both Black and British” while living and working in the imperial metropolis. Unwilling to accept second-class citizenship, Afro-Caribbean migrants formed grassroots organizations to protest racial discrimination, lobbied for legal reform, and repurposed popular Caribbean festivals to secure to their rights as British citizens.

Dr. Kennetta Hammond Perry is Assistant Professor in the Department of History at East Carolina University. She earned her B.A. in History and Political Science at North Carolina Central University and her Ph.D. in Comparative Black History at Michigan State University. Her research examines the history of the Atlantic World with a focus on Black politics, migration, and activism during the post-World War II era. Her work has appeared in the Journal of British Studies, History Compass, and The Other Special Relationship: Race, Rights and Riots in Britain and the United States (Palgrave, 2015).

***

The past decade has witnessed a fresh wave of scholarship on Black Europe, including new monographs, edited volumes, collections of primary documents, and interdisciplinary conferences. When did you first become interested in Black British history?

Perry: My interest in Black British history was initially sparked during my undergraduate years at North Carolina Central University (NCCU), where I took classes and was advised by some of the pioneering historians of Black Britain, Black Europe, and the African diaspora more broadly: Carlton Wilson and Lydia Lindsey. I took a number of courses with Carlton Wilson in modern European history, where we learned about figures like Mary Seacole, Robert Wedderburn, and Olaudah Equiano. At the time, Lydia Lindsey had conducted research on Jamaican women in Birmingham [England], and she was also writing a biography of Claudia Jones, who figures quite predominantly in my work. I was exposed to a type of European history that was very much connected to the history of the African diaspora in my undergraduate experience at NCCU. Therefore, when I entered the doctoral program in Comparative Black History at Michigan State University many of the seeds of this project were already planted.

The book project itself emerged from a graduate seminar paper that I wrote at Michigan State. In the paper, I posed a broad question about the experiences of Black people in Britain during the height of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s. I wanted to know more about the composition of Black communities in the U.K. and the key moments of Black political organizing in Britain.

Your book, London is the Place for Me, takes its title from a hit song by the Trinidadian calypsonian Aldwyn Roberts, who performed using the stage name Lord Kitchener. Kitchener famously performed the song “London is the Place for Me” in June 1948 when he disembarked from the Empire Windrush. Kitchener’s song, as you note, ultimately “became part of the soundtrack chronicling the history of Caribbean migration to Britain following World War II.” How does his song help to illuminate the politics of race, migration, and belonging in postwar Britain?

Perry: In the introduction, I revisit the moment of Lord Kitchener’s arrival in London and I also think about the stakes of the iconic performance of the song. One of the things that’s really important to acknowledge is that Lord Kitchener doesn’t actually need to experience living in the U.K. for him to envision that London could be the place for him. London was a place to which he could lay claim to before actually arriving on British shores. The idea that he could create this song—this representation of his sense of attachment to Britain before he arrives–opened up a way for me to think about his performance as a moment that was important not just because of the news that it made around the arrival of the Windrush, but also for what it tells us about Afro-Caribbean migrants’ affinities and attachments to Britain, their sense of imperial belonging, their everyday notions of citizenship, and their ability to lay claim to British identifications well before living, settling, and creating community in the U.K. So, for those reasons, it was an interesting moment to reconsider.

I also think it’s important to note that Lord Kitchener’s performance takes place at a particular moment—both domestically and internationally. As I try to layout in the introduction, 1948 is a critical year when we’re thinking about race politics globally. It is the year when the Nationalist Party rises to ascendancy in South Africa. It’s the year when President Truman issues the order to desegregate the U.S. military. It’s also the year that Claudia Jones gets arrested for the first time, which is going to put her on the pathway to entering the U.K. and having a profound impact on Black politics in Britain. So I wanted to play with that moment and to think about its utility.

Scholars in the field of Black British cultural studies, including Stuart Hall and Barnor Hesse, have problematized how the arrival of the Empire Windrush is commemorated as an “originary moment” in mainstream accounts of the emergence of postcolonial Britain. While your book foregrounds the experiences of the Windrush generation, you also connect the activism of the post-World War II years to histories of migration and Black resistance in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Tell us more about that.

Perry: Lord Kitchener’s claim making moment is emblematic of a type of politics that preceded the arrival of the Windrush in 1948 and had long been a part of the ways in which people of African descent were thinking about their relationship to Britain–both in the U.K. and more broadly in the context of the British Empire. I really do think it’s that sort of attachment to Britain and the capacity for claim-making that imperial belonging provided that links Kitchener and others in the so-called Windrush generation to older communities of Black Britons and ideas about Black Britishness in the Empire.

If we think about how Kitchener is articulating a claim about belonging and a sense of rightfulness to be in London, the imperial metropolis, it allows us to connect his story to earlier Black activists like Harold Moody and his work with The League of Coloured Peoples in the 1930s and 1940s. For Moody, part of the work of The League of Coloured Peoples involved advocating for people of color and, in particular, people of African descent who resided in the U.K. He was very much concerned with his dual identity as a Black man and as a British subject.

In the book, I also wanted to draw attention to the larger imperial context shaping postwar Afro-Caribbean migrants’ claims to Britishness, which I argue was part and parcel of post-emancipation imperial politics. The British Empire quite literally created a type of discourse about subjecthood and imperial belonging that people of African descent were able to retool for their own purposes in the colonies to make claims about citizenship and to assert rights and identifications economically, socially, politically, and culturally. So what we see in the postwar period is not necessarily new. Rather, it is simply one of the ways in which—to borrow from one the foundational collections in Black British cultural studies—that the “Empire strikes back” in a postwar context marked by the realities of imperial decline. In the book I wanted to try to map out some of those connections and pay attention to the ways in which a focus on Black British political activity sheds light on what scholars including Paul Gilroy, Bill Schwarz and Jordanna Bailkin have described as a type of social and cultural process of decolonization that takes place in the imperial metropolis.

Despite their formal legal status as citizens of the British Commonwealth, Afro-Caribbean newcomers encountered virulent discrimination in London and other cities in the metropole. As you detail, waves of anti-Black mob violence erupted in Nottingham and Notting Hill in 1958 and a group of White men murdered Kelso Cochrene, a thirty-two year old carpenter from Antigua, in 1959. Can you say a bit about the discrimination and violence that Afro-Caribbean migrants confronted in postwar Britain?

Perry: A central aspect of understanding the experiences of a largely Afro-Caribbean first-generation migrant community, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, is the fact that these individuals were trying to resettle. Thus, employment and housing discrimination were two of the key arenas where they experienced open anti-Black racism—what at the time was termed a type of “colour bar.” It was not uncommon to find housing or employment advertisements explicitly barring non-White applicants. In the book, I draw upon Lydia Lindsey’s work, which details discrimination in the employment sector, where Afro-Caribbean migrants faced discrimination in their attempts to secure interviews, find jobs outside of some of the lowest paid tiers of the labor market, and have their educational credentials and previous work history acknowledged. Once hired, Afro-Caribbean migrants also endured discrimination in terms of the conditions that they faced on the job where they oftentimes experienced hostility from White co-workers.

Housing was another critical arena. Access to housing was a really big issue for Black migrants, and that has to be seen within the context of the larger postwar rebuilding process that severely limited access to housing for working-class people overall in the U.K. The housing crisis was really acute in urban areas where you see higher concentrations of Afro-Caribbean migrants, so there was tremendous difficulty in terms of accessing quality affordable housing.

Obviously, as I note in the book, episodes of violence represented some of the most virulent forms of anti-Black racism, which affected Afro-Caribbean migrants’ bodies and their ability to live and walk the streets in their own neighborhoods with a sense of security. In response, the book highlights some of the campaigns waged by Black British organizations including the Inter-Racial Friendship Coordinating Council and the West Indian Standing Conference, which focused on challenging the state to respond to the needs of Black citizens in their efforts to secure safe neighborhoods and adequate police protection. Likewise, it is important to note that organizations like the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination tried to shape the scope of anti-discrimination policy in the mid 1960s by launching a summer campaign to document discrimination occurring among local businesses, housing agencies, and employers against Black and Asian communities in Britain.

In Chapter Three of the book, you suggest that newspaper accounts about the violent “race riots” in Notting Hill and Nottingham and the activities of White vigilantes like the Teddy Boys shocked White readers in Britain and around the world. “These news stories,” you maintain, “contradicted the mystique of British anti-racism that informed the ways that White Britons viewed themselves, their relationship to the Commonwealth, and Britain’s image in international politics.” Can you explain the “mystique of British anti-racism” and its origins?

Perry: In the book, I try to think through the pervasive silence regarding racism in the U.K., which oftentimes became the means to erase histories of the Black experience in metropolitan Britain. When I was examining the “race riots” in Nottingham and Notting Hill and how they become news internationally, I was struck by the fact that international commentators were shocked that “race riots” could occur in British cities. But how can we acknowledge a history of British colonialism—a violent, racist, and exploitative regime that operated globally—but yet not be able to comprehend the idea that “race riots” can happen in the U.K.?

One of the things that I discuss is how narratives about British abolitionism became the conduit through which Britain was able to imagine and caricature itself internationally as a tolerant, liberal, morally virtuous anti-racist nation—particularly in contrast to Jim Crow America. International reaction to the news of “race riots” in 1958 demonstrates the pervasiveness of this view of Britain as a place absent of racism. From the perspective of Afro-Caribbean migrants, I wanted to think about what it meant to gain visibility for your anti-racist movement in a context where the world imagined that anti-Black racism didn’t exist. To both expose and challenge these myths about the British nation, at times Black activists tethered their demands for full citizenship and social justice to internationally recognized images of U.S. racial injustice and Jim Crow as part of a strategy to give visibility to their cause. Places like Birmingham, Alabama, events like the March on Washington (1963), and people like Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Stokely Carmichael, all of whom actually visited the UK during the 1960s, played important roles in helping Black Britons raise the profile of their struggle for rights.

As you highlight in the book, Afro-Caribbean women—particularly Claudia Jones and Amy Ashwood Garvey—played a pivotal role in mobilizing Black migrants in London. Can you tell us more about the specific activities of Jones and Ashwood Garvey and their impact on Black British politics?

Claudia Jones Memorial Photograph Collection, New York Public Library Digital Collections

Perry: I don’t think it’s possible to even talk about this period and Black political organizing without mentioning Claudia Jones. Amy Ashwood Garvey and Jones were comrades in struggle together, but they were also critical players in terms of organizing, mobilizing, and creating communities—Black communities—in Britain during the 1950s and the 1960s.

Furthermore, what is important about these two individuals is that they were pivotal in terms of establishing grassroots organizations. Claudia Jones was active in founding arguably the most important political organ in the U.K. among populations of African descent in the late 1950s and early 1960s—the West Indian Gazette newspaper—of which Amy Ashwood Garvey served on the editorial board. Jones was also influential in establishing a tradition of Carnival beginning in 1959. One of the things that is very interesting about Jones’s work with Carnival, an event that featured steel bands, calypso, beauty contests, dancing and Caribbean cuisine, is that it is reminiscent of the type of merging of social and political life that characterized Ashwood Garvey’s work at the Florence Mill Social Parlour, a local establishment where Black intellectuals including George Padmore and C.L.R. James gathered to socialize, exchange ideas, and cultivate diasporic political networks during the interwar period.

It is also important to note that Jones and Ashwood Garvey were both also very effective in terms of building advocacy organizations. Ashwood Garvey was co-founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (U.N.I.A.), but she was also a member of London-based organizations like the Nigerian Progress Union and the International African Service Bureau. Seeing her involvement later on in organizations that take shape in the 1950s like the Committee of African Organizations and the Association for the Advancement of Coloured People, which Jones is also a part of, shows a continuity between pre- and post‑war activism that cannot be ignored. It is a reminder that we cannot divorce Windrush-era Black politics from the type of Pan‑Africanist work that we usually confine to the interwar period.

New York Public Library Digital Collections

You draw upon an impressive array of written and visual sources to reconstruct the everyday lives and political activities of Afro-Caribbean migrants in London. What specific sources and archives did you find most useful as you wrote the book?

Perry: The project took me to major archives and libraries across England and the United States. But I found the most useful sources in smaller, community-oriented repositories like the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton, the Institute of Race Relations in London, and the local Lambeth Library. These places are staffed by folks who are really invested in trying to preserve contemporary Black British history and to make those records accessible.

In particular, the Lambeth Library has one of the largest existing runs of the West Indian Gazette newspaper. It also has one of the most interesting sources that I encountered during my research: photographs of Afro-Caribbean migrants from the 1950s and 1960s. Many of the photographs are studio portraits taken by Brixton photographer Harry Jacobs. However several of the photographs, some of which appear in the book, were donated by Donald Hinds. Hinds worked as a journalist at the West Indian Gazette alongside Claudia Jones. He’s co-authored a biography of Jones as well as other important literary works about Afro‑Caribbean migration in the 1950s and 1960s. He generously allowed me to use some of his personal family photographs and documents, and those were really gems because working with images offers a different portal to connect with the people you’re writing about. You get to see their smiles. You get to see how they are representing themselves and how they’re portraying intimate aspects of their lives. Oftentimes when we think about politics, we think about it in very public ways, but those family photographs were a constant reminder that politics is deeply personal and intimate. The photos were the kinds of sources that ultimately made the project come alive for me and were the most exciting to work with.

Before we conclude, I want to pose a question about the implications of your work for the present moment. In the book, you briefly discuss the killing of Mark Duggan, an unarmed twenty-nine year old Black man from Tottenham, by the Metropolitan Police in August 2011. Duggan’s killing sparked several days of protests across London and generated a public debate about police harassment and state-sanctioned violence in Black British neighborhoods. More recently, in October 2015, Black activists and scholars in Nottingham held a conference on the #BlackLivesMatter movement. How does the activism of the current generation of young Black Britons compare to the work of the Windrush generation during the 1950s and 1960s?

Perry: What I’m trying to do in the book is to make connections between past and present, particularly in the short epilogue that references Mark Duggan’s death and some of the activism that comes in the wake of it. But I actually think the book is not so much an effort to get people to think about comparisons, but rather, it is an attempt to shed light on the larger historical context necessary to understand contemporary Black protests and claim making around citizenship and belonging in Britain. I hope that the work that I’m offering in the book provides a historical narrative for the protests that occurred in the aftermath of Duggan’s death and sheds light on longstanding concerns around policing and racial injustice in the U.K.

Some of activism that is referenced in the book during the 1960s revolves around Black British activists’ campaigns to collect data about the discrimination that people experienced at the hands of police. Also at the 1945 Pan-African Conference in Manchester, Amy Ashwood Garvey chaired a session on the “colour problem” in Britain, where the issue of race and the carceral state was actually raised by one of the delegates. Thus, Black people’s disparate experience in the criminal justice system is something that’s on that agenda as early as 1945. I think the fact that this is something that Black Britons are still protesting about in the twenty-first century helps to explain the urgency of this moment. The present movements are part and parcel of a much longer history of Black protest against White supremacy and anti-Black violence.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Great interview, and I look forward to reading the book! I especially appreciate the emphasis on the interconnectedness of civil rights movements in the UK, the US, and elsewhere around the world, and on the work of Claudia Jones

Thank you so much for this interview. It stirred so many memories for me .

I am part of the generation of baby-boomers, so called mixraced ,afrcarb/white children who are the holders of the memories, of the black Britons.

I was born on 1950 in Manchester. Many of the musicians moved out of

London, looking for work .

I grew up with many uncles , Kitchener, Terror amongst them,and gained a strong sense of humour,identity that my father , Jerome Benjamin,and his friends passed on in the Caribbean Carnival.

They had a great sense of belonging to Empire,that empowered them , to put down roots but despite the racism , were able carve out a future for themselves and their families