Not Another Slavery Movie

Even before controversial director Nate Parker debuted his Nat Turner movie, The Birth of a Nation, black voices emanated from Black Twitter and other social media to bemoan “not another slavery movie.”

This sentiment seems to convey a need for black moviegoers to avoid intergenerational wounds from which we have yet to heal. Such failure to heal has to do with this nation’s willful national amnesia that seeks to rewrite a 300-year-old history of enslavement and dehumanization as a necessary evil or, worse, as institutionalized justification for racism. White supremacy is the alibi for American democracy. It excuses the evils of slavery.

No wonder, then, that everyone – both black and white – cannot bear witness (even through fiction or the movies) to an era that exposes the lies of democracy. Perhaps this lens of “another slavery movie” can help us make sense of our present; such is Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation.

The film explicitly opens with a fabled scene of young Nat Turner’s father out in the night in search of food for his hungry son when he is suddenly halted by a group of slave patrollers. Their condescending tones, their quickness to draw the gun and kill any black man who dares to challenge their authority, are far too reminiscent of the present. Nat Turner’s father could easily be a nineteenth-century Alton Sterling, Philando Castille, Kevin Scott, or Michael Brown. But here, Parker flips the script. Here, Nat’s father escapes and manages to even kill one of his oppressors.

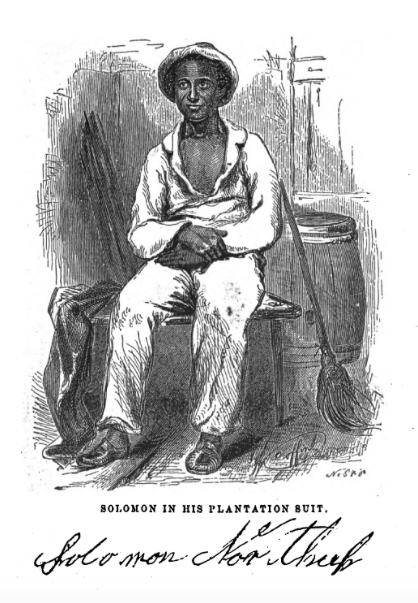

Despite its invocation of the present through history, Parker’s film failed to attract an audience, even though other “slavery movies” – Quentin Tarantion’s Django Unchained (2012), Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave (2013), and Amma Asante’s Belle (2014) – drew considerable box office and fans. It would be easy to say, as some on social media have, that Parker’s controversial past in which he was on trial for the gang rape of a co-ed while he was in college – combined with his lack of remorse for the alleged victim who eventually committed suicide – soured the potential enthusiasm for this film.

However, the marketing for this movie was going to be a challenge. Apart from Tarantino, whose reputation sold Django’s box office more than the story itself, all of the above-mentioned movies started with small releases – drawing larger audiences on the strength of word-of-mouth, given their novel and artistic storytelling. The storytelling in The Birth of a Nation, however, suffered from a weak script and failure of imagination, despite some key moments of catharsis. So word-of-mouth would not help this film. Still, the rebellion scene is an exhilarating one and a much-needed reminder that we don’t have enough of these scenes in cinema. Apart from what historian Vanessa Holden describes as a “Southampton Rebellion” – one based on a communal uprising that included both women and men and not focused solely on Nat Turner’s leadership – where are all the glorious movies about the various slave uprisings that took place throughout history?

Where is the movie on Denmark Vesey’s slave revolt that took place nearly a decade before the Southampton Rebellion? When will we finally get an English version of the Haitian Revolution (French television had already produced a miniseries), which led to the first independent black nation – an achievement for which an impoverished present-day Haiti is still paying the price? How long until we get to see Harriet Tubman leading the Combahee River Uprising, taking place two years before the the official end of chattel slavery? An HBO film starring Viola Davis is in the works, but will her epic freedom struggle get the big screen treatment?

And even when such freedom struggles are finally filmed, will there be an audience for it? Parker made his film on a modest budget. The record-breaking sale of his film at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year – in which Fox Searchlight paid $17 million for distribution rights – ensures that his labor was not all in vain. And yet, The Birth of a Nation comes off as a vanity project – not just in the creation of a “superhero” in the figure of Nat Turner but in the embodiment of Parker as Turner himself. In every way, Turner is presented as the “exceptional Negro” – a sentiment also expressed in Django Unchained – which prevents us from seeing how he connected a “liberation” theology into communal resistance.

While I am less concerned about “historical inaccuracies,” which led Leslie M. Alexander to call the film an “epic fail,” I do expect our art to capture the “truth” of a story – whether this includes or eschews the “facts.” Historical records reveal that Turner (like most of the leaders of slave revolts – Vesey, Tubman, the Haitian revolutionaries) was inspired by religious vision and prophecy. The Birth of a Nation presents such visions as snippets of signs and wonders – a solar eclipse, blood dripping on corn, an amateurish vision of an angelic woman with wings – and intuits that Turner’s theological bent was developed from witnessing the cruelty visited on the enslaved community when he was rented out as an itinerant preacher visiting various plantations. He learned to read the Bible as a small child, courtesy of a benevolent white mistress, and yet we are never presented with her motive for defying anti-literacy laws that forbade slaves from learning to read and white. Turner’s literacy leads to his militant interpretation of biblical verse, which ironically justifies these anti-literacy laws.

Turner’s rhetorical gifts are exploited by white slaveowners who force him to preach “meekness and obedience” to his fellow slaves, under the ever watchful eyes of their owners. What the film rarely shows is how that preacher-talk changed when they escaped the dominant gaze. We know from historians that “everyday resistance” – as the late Stephanie Camp calls it – existed in the slave community, which included “stealing away” into the woods and holding their own religious and secular meetings and moments of joy and pleasure even when the penalties were high.

The Birth of a Nation missed an opportunity to create a nuanced rebellious community. Rather, we are led to believe that Turner is simply a blessed and charmed man, nurtured by the women of his life – first his mother and grandmother, then his white mistress, and later his wife Cherry (played by Aja Naomi King). The first time Turner and Cherry meet, a smitten Nat convinces his master to purchase an unkempt and fierce Cherry, who is sexualized and humiliated on the auction block. His ability to transform her from a brutalized woman (who most likely had already survived rape) into a soft, cleaned up, and dainty lady is part of Turner’s charm. Cherry becomes a respectable and presentable wife-to-be, worthy of courtship and later Turner’s vengeance after she is gang-raped by a group of slave patrollers.

Interestingly, Cherry seemed a much more fascinating character as a fierce and unkempt woman resisting Turner’s touch. For me she invoked Sukie, the slave woman who pushed her master in a pot of hot soap and, when sold on the auction block, invited potential buyers to check the “teeth” under her skirt. So many of our enslaved women enacted everyday resistance in different ways. Unfortunately, too many “slavery movies” cannot envision such figures as existing independent of black men’s tropes for vengeance and inadequacy, thus becoming silenced in the narrative, as Salamishah Tillet argues.

McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave comes close to giving voice to women like Patsey, Eliza, and Mistress Shaw, but Patsey’s brutal whipping scene reduces her to the “ultimate victim” trope. Asante’s Belle focuses on a free mixed-race woman in the aristocracy, whose slave mother remains invisible. And Django Unchained’s Broomhilda is more a concept than an actual character.

The Birth of a Nation continues this silencing of the enslaved woman. Nonetheless, how marvelous would it have been if Cherry and her fellow enslaved women (like Esther, played by Gabrielle Union, who chooses silence as a rape victim) transcended their abuses – like their fellow men – and joined in the uprising, as historians suggest women did?

While many may impugn Parker’s patriarchal narrative as the work of a suspected rapist, it is just as easy to attribute this limitation to his Christian worldview, which sharply curtails the artistic vision of Turner as both a prophetic and militant leader joined by his community of fellow slaves. The uprising may have made for a cathartic moment in movie-watching, but the film needs more substance.

That said, The Birth of a Nation is worthwhile and definitely helps to resurrect the story of Nat Turner and others involved in the Southampton Rebellion. What we now need are new and innovative approaches to the “slavery movie” genre that can give substantive voice to women beyond slave-rape narratives, that can boldly envision various acts of slave resistance, and that can disrupt the iconography of slave suffering and violence – the whipping post, the bit, the lynching. The more we can humanize the subjects of this era, the more we can process the history. If we must bemoan “another slavery movie,” let it only be when these particular goals have not been met.

Janell Hobson is an Associate Professor of Women’s Studies at the University at Albany, State University of New York. She is the author of Body as Evidence: Mediating Race, Globalizing Gender (SUNY Press, 2012) and Venus in the Dark: Blackness and Beauty in Popular Culture (Routledge, 2005). She also writes and blogs for Ms. Magazine. Follow her on Twitter @JProfessor.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

After watching this movie I cried all the way home in my car. The humiliation that our people have suffered is horrific and I can’t believe that the white people back during this time had not a one ounce of remorse. It is heart breaking and i am still sadden this morning just from the images. We have to learn to embrace one another with sincere love, after all haven’t we been through enough?

Kim Miller

Kim,

I too cried…

I felt ashamed that as I was leaving the theater, people witnessed me sobbing. Normally I’m able to control my emotions but this time grief overwhelmed me.

I too can’t believe that people can be so cruel and although I love and believe GOD with my whole being, i wondered, wonder, am wondering why??

Great blog. Loved how you explained how Black women ideas, issues, lives and agencies continuing get ignored

Although heartwrencing, I sorrowfully admit that I did enjoy Nate Parker’s version of Nat Turner’s narrative.

Honestly, I think I was desperately craving a visual that would solidify what my seventh grade teacher ignited when she had courageously deviated from the PSD’s curriculum to share what little she knew of this great rebel’s life.

In 1977, based on what the teacher shared, and because I found it hard to relate to an antiquated time period, Turner felt mythical -turned hero.

With pride, I had imagined a human being – being human enough to care deeply for the humanity of his people, and today in 2016, what Nate Parker has done is bring Turner’s narrative to life, providing vignettes of what a brethren’s love, courage , and urge to defend and even die for look like… at all cost and any means necessary.

It’s unfortunate that I can’t justly and adequately articulate why I so strongly felt a need to view Nat Turner’s narrative on the big screen because indeed I have read the books…maybe it’s because today at an alarming rate “black lives” are being extinguished and I might be searching the ancestors for answers from ( by the way, visual aids are very impactful)… I wanted to see their yearning and their guts to save a people, a people who have for over 400 years and still today can’t overcome ??

What I think I walked away with was a deeper sense of LOVE, as a people to love on each other like never before so that others will feel our self respect forcing them to revere us , too.

In closing, I am one who will never tire of seeing “slavery movies” because although terribly hurtful, in my seasoned years, I find it necessary to revisit the ancestors no matter what the medium… because #slavelivesmatter and it’s the least i can do… showing respect for their struggles… it is my way of saying that whatever they endured was not done so in vain.

…keeping the memories and stories alive!