“The Negation of the Negation in the World System”: Introducing Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism

This is the first day of our roundtable on Cedric Robinson’s book, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. We begin today with introductory remarks by AAIHS blogger Paul Hébert. In this post, he sets the frame for this roundtable’s exploration of Black Marxism through the emancipatory possibilities of the Black radical tradition.

Paul Hébert is a recent graduate of the doctoral program in History at the University of Michigan. His dissertation, “A Microcosm of the General Struggle: Black Thought and Activism in Montreal, 1960-1969” examined how black Canadians, West Indians, Africans, and African Americans living in and passing through Montreal contributed to the development of schools of Black Power thought and action that were not simply reflections of Black American radicalism, but intellectual and activist movements that responded to specific local dynamics. Canada’s imperial identity and its enduring ties to the British Empire shaped public debate about local and international anti-racist activism. His chapter, “‘Thought is Action for Us’: New World, Lloyd Best and the West Indian Postcolonial Left,” examines the New World Group, one key force in the shaping of postcolonial West Indian radical thought. It was featured in A New Insurgency: The Port Huron Statement and Its Times, edited by Howard Brick and Gregory Parker and published by Maize Books in 2015. Follow Paul on Twitter @DrPaulHebert.

Paul Hébert is a recent graduate of the doctoral program in History at the University of Michigan. His dissertation, “A Microcosm of the General Struggle: Black Thought and Activism in Montreal, 1960-1969” examined how black Canadians, West Indians, Africans, and African Americans living in and passing through Montreal contributed to the development of schools of Black Power thought and action that were not simply reflections of Black American radicalism, but intellectual and activist movements that responded to specific local dynamics. Canada’s imperial identity and its enduring ties to the British Empire shaped public debate about local and international anti-racist activism. His chapter, “‘Thought is Action for Us’: New World, Lloyd Best and the West Indian Postcolonial Left,” examines the New World Group, one key force in the shaping of postcolonial West Indian radical thought. It was featured in A New Insurgency: The Port Huron Statement and Its Times, edited by Howard Brick and Gregory Parker and published by Maize Books in 2015. Follow Paul on Twitter @DrPaulHebert.

In his 1967 essay, “Independent Thought and Caribbean Freedom,” the Trinidadian scholar Lloyd Best wrote about the economic, political and cultural forces that undermined the sovereignty of newly-independent West Indian nations. At the center of Best’s analysis was an epistemological argument: scholars should study the Caribbean through theoretical lenses informed by the specific histories, cultures, and experiences of the West Indian people, and not with approaches rooted in European thought; analysis of the Caribbean needed to be grounded in “how we relate to ourselves and to the wider world in which we live.”1

Best was particularly critical of the influence of Marxism on West Indian radical thought. He argued that Marxism could not account for social realities that fell outside of its established categories, making it too narrowly-focused to provide meaningful conclusions about the world beyond Europe and thus too restrictive a basis on which to build a radical politics. A decade later, Best’s colleague, the Jamaican economist George Beckford argued that the labor regime that had been imposed on the West Indian people by an “international racist system” had created social groups that, because they were not “homogeneous in the classical sense,” did not qualify as “classes” in strict Marxist terms; race, not class, was the primary social dynamic that drove the exploitation of the West Indian people. Marxist theory that did not account for race and integrate race with class analysis, Beckford argued, could not meaningfully grasp West Indian society.2

The gap between Marxism’s assumed universalist reach and its actual grasp is a central concern of Cedric J. Robinson’s indispensable 1983 book, Black Marxism. Echoing critiques like those of Best and Beckford while expanding the scope of his analysis beyond the West Indies to address a global system of exploitation and oppression imposed on the African people, Robinson writes that Marxism’s principal “conceit” was to assert that historical materialist analysis explained all of human history, when in fact it could only meaningfully address “merely one fraction of the world economy”–that of bourgeois Europe (p. xxix).

As Joshua B. Guild writes in his contribution, Black Marxism demands much from the reader. Robinson makes a two-fold argument about capitalism and radical resistance to it. First, he reframes the history of Western capitalism (and ultimately Western civilization) by centering his analysis on the role of race and racism in its development; capitalism, Robinson argues, was from its earliest antecedents in early modern Europe, built on principles of racial exclusion and white supremacy. Second, he traces the history of the specifically African modes of resistance – the Black radical tradition – that emerged in response to racial capitalism.

Because Western radical historiography is blind to how capitalism was built along racial lines, it is equally blind to the emancipatory possibilities of the Black radical tradition, which emerged in opposition to it. For Robinson, the Black radical tradition is the “negation of the negation in the world system” – not a revised Marxism or a synthesis between African and Eurocentric radical traditions, but “a new vision centered on a theory of the cultural corruption of race” (p. xxxii). Absent analysis that accounted for the central role that racial ideologies played in its origins and developments, capitalism provided no tools able to undo it. It was only when Marxist ideologies confronted African revolutionary thought that Marxism became radical enough to act as what it mistakenly believed itself to be: a totalizing theory of revolution. Being rooted in a “singular historical identity” that exists in opposition to Western racism and oppression, the Black radical tradition was able to challenge both racial capitalism and the Eurocentric progressive ideologies that were blind to the foundational role of racism in the structures they attacked.

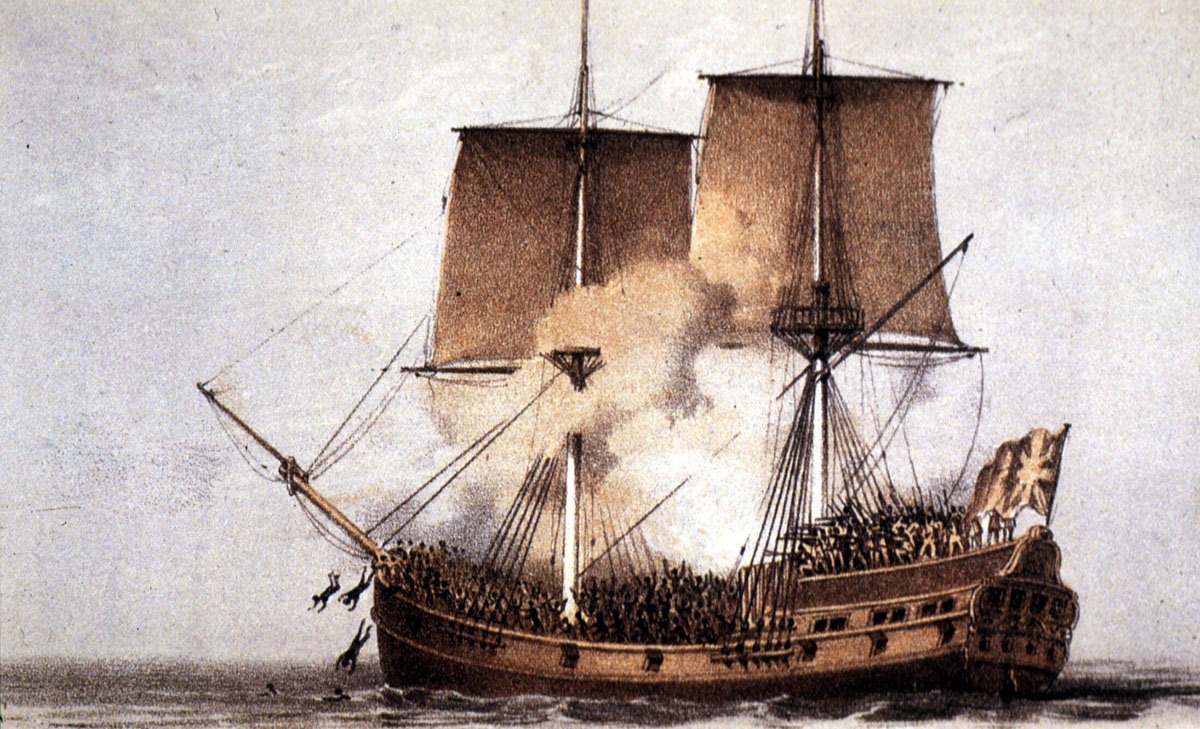

In Robinson’s analysis, history played a central role in the development of racial capitalism, beginning from how the erasure of the African past was a key strategy in the creation of “the Negro” as a laboring subject. In “Thinking With Black Marxism,” Jennifer L. Morgan, a historian who studies enslaved women in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, writes that Robinson’s analysis forced her to engage with how the erasure of her subjects’ history was a vital element in the rise of racial capitalism. The scrubbing of the African peoples’ history that played a central role in the development of racial capitalism and blinded us to the radical politics at the heart of resistance to New World slavery continues to shape scholarly inquiries into the links between slavery and capitalism.

Recent studies that have revived the Williams thesis and traced the links between Atlantic slavery and the emergence of modern capitalism, Morgan argues, overlook the longer history of black resistance by focusing on the nineteenth century and not engaging with the histories of enslaved Africans in the earliest years of the Atlantic trade. Failing to account for that longer history, Morgan writes, makes it impossible for us to see Africans “as people who enter into captivity with a wealth of history, knowledge, experience, and worldview firmly in place,” blinding us to key components – distinctly African in character – of the history of the Black radical tradition.

Robinson presents the Black radical tradition as a school of radical thought and action whose broad scope allowed for an understanding of capitalism that was not possible in a Eurocentric Marxist framework. That said, like many books written by Marxist male scholars in its time, Black Marxism suffers from an important omission – it contains virtually no mention of the gendered dynamics of racial capitalism or of women’s resistance to it. While this is a serious shortcoming, as Carole Boyce Davies writes in her contribution, “A Black Left Feminist View on Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism,” framing the absence of gender in Robinson’s analysis as simply a weakness is less productive than understanding that such omissions can be productive in that they reveal the gaps in a mode of analysis that opens up the possibility of a “creative leap to a new set of positions”–one that, in the case of studies of the Black radical tradition, has been taken up by later generations of black feminist scholars.

In Robinson’s analysis, the Black radical tradition was forged in protest; it is a body of political theory inherently informed by struggle. Boyce Davies’s contribution concludes with a discussion of Black Marxism’s relevance at a time when she sees something of a theoretical vacuum with the passing of voices like Robinson and Stuart Hall and a tendency within the Black left to look backwards “without theoretical guidance for the future.” Black Marxism’s conclusion addresses a number of contemporary concerns that resonate more than thirty years after the book’s publication, including the “imprisonment [and] use of lethal force by public authorities and private citizens” against African-Americans and the fact that “petty humiliations of racial discrimination have become epidemic.” Robinson argues that while it is not the responsibility of any one group of people to undo these abuses, a self-conscious Black radical tradition, one “formed in opposition to” Western civilization, “is one part of that solution” (p. 318).

In his essay, “Conjuring the Black Radical Tradition,” Austin McCoy examines how current protests against white supremacy and police violence in the United States unfolding under the banner of Black Lives Matter constitute a contemporary “conjuring” of the Black radical tradition. McCoy notes that mass disruption has always been a key strategy in the delegitimization of the ideologies, institutions, and practices that underpin and maintain white supremacy. Mass disruption is a potential strategy to intensify the Black Lives Matter movement, notably with activist/journalist Shaun King’s recent call for a massive economic boycott in protest of racism in the United States. McCoy reads Shaun King’s proposal against Martin Luther King’s appeals for “massive civil disobedience” in protest of the Vietnam war and poverty in the United States. Such a tactic, McCoy argues, coupled with the concept of prison abolition, would strongly link the issues of racist police violence and mass incarceration to the system of racial capitalism and could thereby possibly “force a reckoning.”

On Saturday, Robyn Spencer offers concluding thoughts on Robinson’s book and our contributors’ engagements with it. Black Marxism is a rich text that continues to challenge scholars more than thirty years after its publication. We look forward to discussing this crucial text with you. Many thanks to our contributors for sharing their thoughts with us.

Excellent summation that will conclude with the insights of Robyn Spencer. Thank you for your time and effort.

…and thank you for reading and your kind words.