The FBI and the Mischaracterization of Bayard Rustin

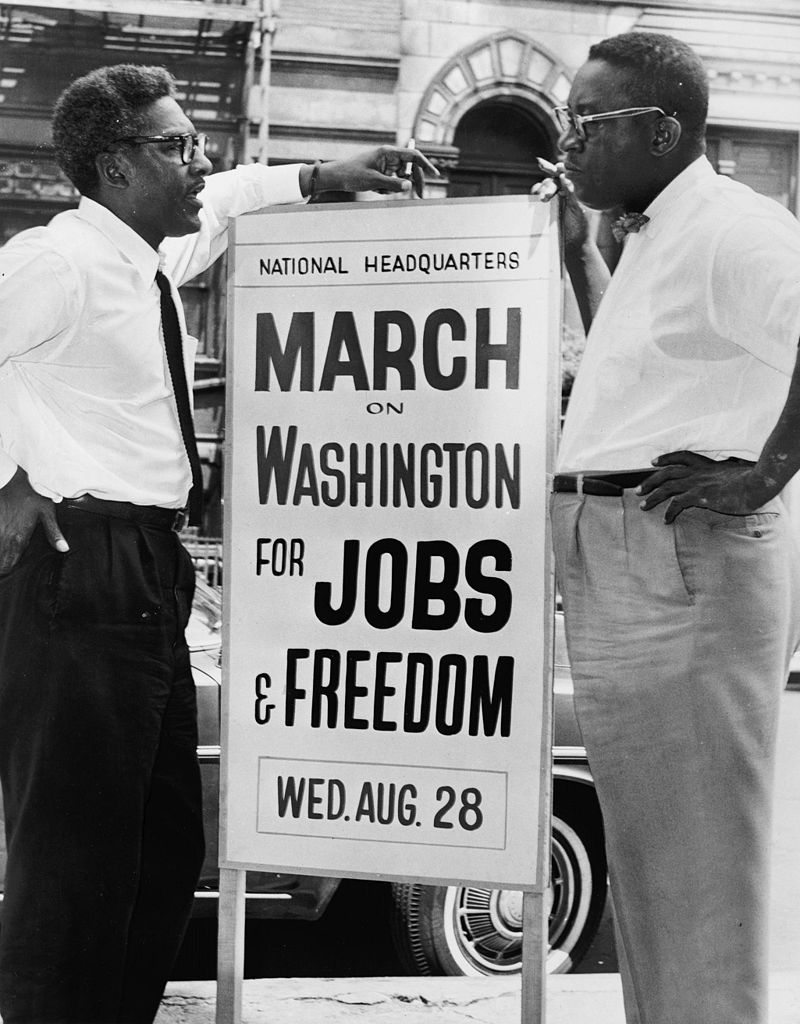

On November 22, Muckrock.com published a disturbing article claiming that Bayard Rustin “was working for the CIA.” The essay created quite a stir, reviving fears that one of the 1960s most beloved activists was possibly an active Informant for the government and an agent against democracy. The accusation, however, was spurious and mendacious on its face.

A cursory reading revealed that the essay had no evidence for such a claim. The narrative noted that Rustin “worked” for the CIA, but included documents that provided no evidentiary backing to the commentary. The four pages which followed at the bottom also made no reference to Rustin or possible collusion with the CIA. Finally, the link which allowed readers to view more documents did connect to additional FBI papers; they were not about Rustin but files related to Scientology. Setting aside for the moment that one can read from this site how the “CIA studied the impact of space storm on psychic powers”—the article’s impact did more than amount to a weekend dissemination of misinformation via Facebook. It cast aspersions on Bayard Rustin’s legacy, and exposed the necessity of recognizing the state’s use of Tipsters, Informers/Informants, and Infiltrators.

As Robyn Spencer wrote in COINTELPRO 2017, state action against radical black activists (and I would suggest any black activist) is nothing new. As both history and recent events show, media misinformation is a powerful tool for undermining leadership, organizations, and public trust. Spencer’s essay also reminds us that FBI covert campaigns included everything from surveillance to infiltration. But greater than any other, the infiltration ploy breeds more anxiety than any other tactic. Your closest ally could be your most dangerous enemy. The ominous character of such a strategy instills a fearful foreboding about allies and activism. It also explains why revelations about purported informants take on a kind of sensationalist intrigue.

However, historians must step carefully into this void, and parse out the real from the unreal. Online news sites can prove misleading at best, and a cover for state action at worse. While the American public endures revelation after revelation of Russian media meddling, African Americans scholars know fully well that this is not just the Russian government’s domain. Given COINTELPRO’s past and its resurgent present, determining what is real and unreal is an act of discernment that first begins with the source.

Muckrock is a media/research website designed to facilitate requests for information via the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). The findings are subsequently published on its website, without peer or scholarly review. The site endeavors to ease complications surrounding FOIA requests, explain document exemptions, and counter request rejections. The automated process and Muckrock’s monitoring of state policies that seek to deny access is, in fact, an important service. However, Muckrock’s popularity is partly based on the information that it finds. The more sensational the revelation, the more likely an increased readership. But, the absence of scholarly injection is deeply problematic. Readers either misunderstand or lack historical context for what they see.

For example, the “Norman Thomas” group referenced in the Muckrock article likely referred to the CIA backed Committee on Free Elections in the Dominican Republic. The organization acted as a “nonaligned” international observer for the 1966 presidential elections which pitted socialist presidential candidate Juan Bosch against U.S. backed candidate, Joaquín Balaguer. Although previous scholarship confirmed that the CIA provided funding for the committee, only Norman Thomas confirmed and expressed regret for secretly accepting funds from the agency. Rustin, along with Victor Reuther and Allard Lowenstein (not named among the Thomas group), may or may not have been witting participants. Thusly, Rustin’s association with a CIA backed committee is neither new information, nor confirmation of open complicity with the state.

That said, the problems of source only partially tell the tale. Ultimately, accusations that activists “worked” for a state agency lack nuance or complexity. What does it mean to “work” for the FBI or CIA? And, under what conditions does that work fall? RevealNews.org published a similar accusation about former Black Panther Party member, Richard Aoki. The online news site declared that Aoki over several years provided detailed information to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Reveal also provided damning evidence from newly released FBI documents on the Black Panther Party which pointed to Aoki’s service as an Informer (I chose this term deliberately, and I will soon explain why) for the FBI. The exposé was heartbreaking for those who accepted the claim or condemned as an outrageous lie by freedom activists and supporters. Still, questions lingered regarding what information Aoki offered and the context under which he gave it.

Most historians remained relatively silent on the matter, choosing not to grapple with the idea that one of the most stalwart freedom fighters of the 1960s might be an Informer. Still, we do well to grapple and explain the nature of the beasts—both history and state surveillance—with which we wrestle. Not every interaction with a government agency can or should be read as aggressive action against the freedom movement. By contrast, not every person is an innocent, unknowing bystander. Designations might help to clarify how we understand these interactions and provide, by its connotation, a helpful historical context for understanding how to classify individuals who give state agencies information.

Given that both the FBI and the CIA operated and depended on secret monetary, political, organizational, and individual associations, many persons may have unwittingly found themselves providing details on persons or events. At best, Bayard Rustin only visited the Dominican Republic and observed its elections. At worse, he contributed broadly known facts as an information source. Any number of persons might fill this definition, including a Cleveland, Ohio, Tipster who informed the FBI on local CORE protests openly available. Tipsters generally lack any background knowledge on the person to whom they speak, the purposes and use of this information, or the degree to which it may be used to inflict damage on people or organizations. These individuals also tend to provide publicly available, commonly known facts which do not act to disrupt an organization or its demonstrations.

Tipsters are distinct from the second classification, Informers/Informants. State agencies cultivate ties with Informers/Informants as long term sources of data. Informers (the lesser level of the two designations) or Informants may or may NOT supply material which injures or undermines organizational survival. Though these persons are aware to whom they give information, they may (informant) or may NOT (informer) have a choice within those circumstances. Thus, coercion or money may reside at the heart of an Informer/Informant’s motivation. Though compulsion (violent or verbal) may generate some level empathy, those receiving remuneration will not. Spies in Mississippi revealed that Percy Greene, an editor of the Jackson Advocate, was a rather infamous Informant for the state surveillance agency, the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission. He also received monies for his efforts to intervene in civil rights activities, later confirmed in the Sovereignty Commission Papers. But, Greene was ineffective—due, in no small part, to the perception by many in the black community that he was a pariah and “uncle Tom” figure. As Mississippi NAACP youth activist, John Frazier noted, “We all knew he was telling it.”

Far more dangerous actions stem from the final group, Infiltrators. Neither history nor scholarship is kind to the infiltrator, but they too may be individuals pressed (violently or verbally) into service for state agencies. Unlike Tipsters or Informer/Informants, Infiltrators deliberately enter spaces with the expressed intent to disrupt. The task to undermine may originate from their own actions or via information deemed actionable by the FBI or CIA for intervention. The notorious assassination of Chicago Black Panther Fred Hampton uncovers the violent repercussions of an infiltrator. Infiltrator William O’Neal mapped out the panther leader’s apartment, and these details provided the basis for a police raid that led to Hampton’s murder. Though O’Neal claimed he had no understanding of the police’s full intention, he was forever marked by the experience, eventually committing suicide in 1990.

Though online news sites may determine that such distinctions are irrelevant or unimportant, readers must become smarter in discerning historical context. Otherwise, “new revelations” like the Rustin/CIA claim can engender inaction, falsify the historical record, ignore historical and human complexity, or undermine the lessons which kept a people’s movement going. Worse, the aftermath obscures the state’s role as the culprit and progenitor of the Tipster, Informer/Informant, and Infiltrator. Headlines that distort history and state action, illuminate nothing about the people they purport to expose nor the historical moment in which they lived. In the age of a new COINTELPRO, what we read must be read through the lens of state surveillance, media misrepresentation, and the reality that black resistance for freedom in any form is extremism in the eyes of America. In this environment, there is no room for yellow journalists to tamper with history nor for us not to know the difference.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.