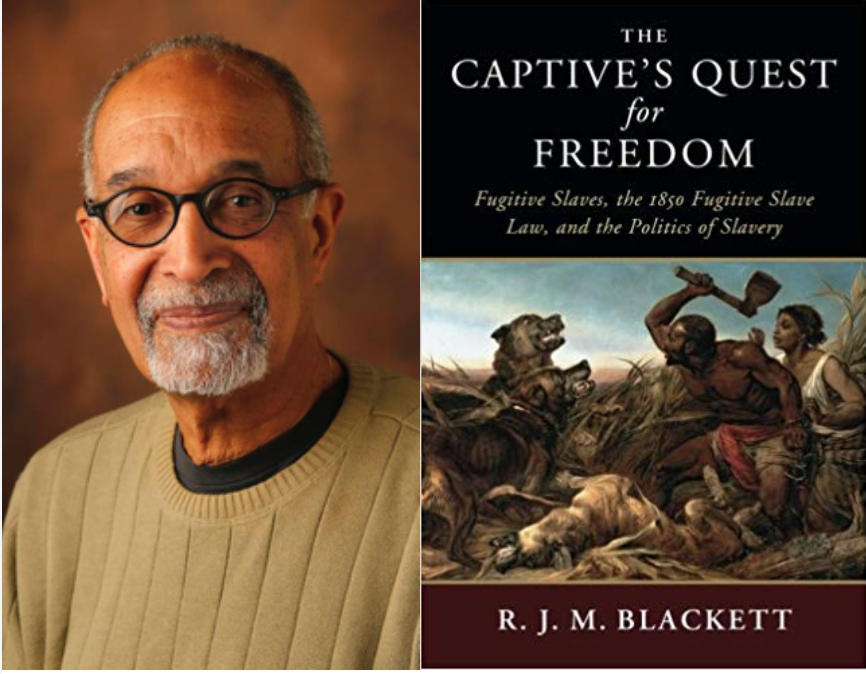

‘The Captive’s Quest for Freedom’: An Interview with Historian Richard Blackett

In today’s post, Rachel Zellars, contributor for Black Perspectives, interviews historian Richard Blackett, about his new book, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (Cambridge University Press, 2018). Richard Blackett is the Andrew Jackson Professor of History at Vanderbilt University and an historian of the abolitionist movement in the US, particularly its transatlantic connections and the roles African Americans played in the movement to abolish slavery. He is the author of Building an Antislavery Wall: Black Americans in the Atlantic Abolitionist Movement, 1830-1860 (Louisiana State University Press, 1983); Beating Against the Barriers. Biographical Essays in Nineteenth-Century Afro-American History (Louisiana State University Press, 1986); Thomas Morris Chester: Black Civil War Correspondent (Louisiana State University Press, Da Capo Press, 1989); Divided Hearts. Britain and the American Civil War (Louisiana State University Press, 2001); Making Freedom: The Underground Railroad and the Politics of Slavery (University of North Carolina Press, 2013); editor, Running A Thousand Miles for Freedom: The Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery (Louisiana State University Press, 1999).

Rachel Zellars: Could you talk about your process for this book a bit, and how you came to settle on each chapter’s subject matter?

Richard Blackett: The chapters were organized in an attempt to answer those questions. It required me to look into the legislative history of the law, one that took almost nine months of debate and the suspension of much more important congressional business. The law was needed because proponents of slavery said it was in spite of warnings that it would be resisted. This led to an analysis of the process by which the law was put into effect and what resistance it encountered. The passage of the law was also a boon to proponents of the colonization of free Blacks outside of the US. The first third of the book covers those issues. The rest of the book is devoted to bringing the enslaved into the debate about the future of slavery. By their actions they not only defied the law they also asserted their commitment to freedom. How they did is best answered by looking at the points of maximum tension, the places where slave and free states meet. Hence, the coupling of states across the slavery divide.

Zellars: The amount – and kinds — of archival materials in this book are tremendous. Can you talk about your reliance on newspapers and what kinds of stories they provided?

Blackett: One way to get at what those who have left us few records think about the conditions in which they find themselves is to look at what they did. That forces us to look in those places where the action took place: from where the enslaved left, the places where they were caught and what happened at those points of conflict. The secret, I discovered, was to look for the failures, for these captures and renditions provide invaluable insights into the nature of the conflict. Newspapers are a rich source to answer these questions. They covered events extensively. Rendition hearings before commissioners and the trials of those caught aiding escapees were also invaluable. From them we get a picture of the levels of resistance to the law, the nature of that resistance, as well as the federal government’s determination to enforce the law. Most significantly, they provide us with the sort of details we need to paint a picture of the individuals involved. That is especially critical if we want to give voice to the enslaved and giving them voice requires us to tell the stories of their actions.

Zellars: What can we learn from the activism of white and Black women resisting the Fugitive Slave Act (FSA), especially women like Lucretia Mott? How did they organize differently?

Blackett: The role of Northern Black and white women who resisted the law and aided fugitive slaves is a vital part of the story but one that is not always easy to decipher. There is no doubt, white women were major figures in the organized resistance but they generally operated in the background. It is even harder to get at the contributions of Black women. The records here are sparse. There were moments during hearings in major cities such as Philadelphia where they were a major presence. They were there to lend support especially if the accused was female. Lucretia Mott made her presence felt at the majority of hearings in the city. We also get glimpses of the activities of Black women at these hearings. Observers commented on the fact that they filled hearing rooms and were leading figures in efforts to free captives. One of the most prominent incident involved Harriet Tubman who played a pivotal role in the rescue of Charles Nalle in Troy, New York.

Zellars: How were Black children uniquely impacted by the FSA?

Blackett: This is not easy to answer. Children usually come into the picture when one or both of their parents were returned. In a handful of incidents when parents who had escaped years before and had started a family were caught, the question of what was to become of their free-born children became central to the debate. If, as slaveholders insisted, the child inherited the status of the mother then there could be only one resolution. Opponents countered that a person born in a free state, a state that had earlier emancipated its slaves, was free. Both sides were faced with a practical and tricky dilemma: should the family be separated, the former slaves returned south, the free-born remaining where they were?

Zellars: Can you talk a bit about the role that Personal Liberty Laws played in undermining the FSA?

Blackett: Many Free States passed laws meant to impede the return of fugitive slaves. Collectively they were labelled Personal Liberty Laws. The Supreme Court had ruled in 1842 that although the federal fugitive slave law must be obeyed states had no obligation to assist in renditions. Subsequently, a number of Northern states passed such laws. Pennsylvania, for instance, refused to allow its prisons to hold those suspected of being fugitive slaves. At a time when there were no federal prisons in the state, this left slaveholders and their agents vulnerable to attacks from Black communities opposed to slave renditions. By the end of the decade, the existence of these laws, and the apparent lack of enforcement of the FSL by the North, secessionists believed was justification enough for leaving the Union.

Zellars: In your study, what impressions and experiences did fugitive slaves describe regarding Canada as an imagined site of freedom?

Blackett: We know from letters written by escaped slaves as well as the reports of observers that Canada was always an ultimate goal even for those who broke their journey in a Free State. Following the passage of the law, scores fled Northern Black communities for the safety of Canada. Nearly two hundred left Pittsburgh in the final months of 1850. Canada became the ultimate sanctuary a place where escapees were free from both their former owners and the law. Letters to family and friends spoke of their new freedom. As one escapee put it in a letter, he had let his feet feel for Canada so his master could feel it in his pocket. In reaching Canada, this slave had found asylum, asserted his freedom, and hurt his former master economically.

Zellars: In what ways were you able to see Canada, especially Canada West, anticipating the FSA and preparing for the likely influx of enslaved with its passage?

Blackett: There is little evidence Canada was prepared for the influx of former slaves. In fact, many commentators expressed surprise by the rapid increase in the weeks and months after the passage of the law. Established Black communities in Canada West did what they could to welcome and provide for the new arrivals, and abolitionists societies in the US raised funds to provide for some of their needs. The decision to go to Canada was not taken lightly especially among those who escaped over the Christmas holidays. Some arrived in desperate straits in need of housing and adequate care. When arrivals spiked, as they frequently did, there was even greater demand on already scarce resources.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.