The Black Convention Movement and Black Politics in Nineteenth-Century America

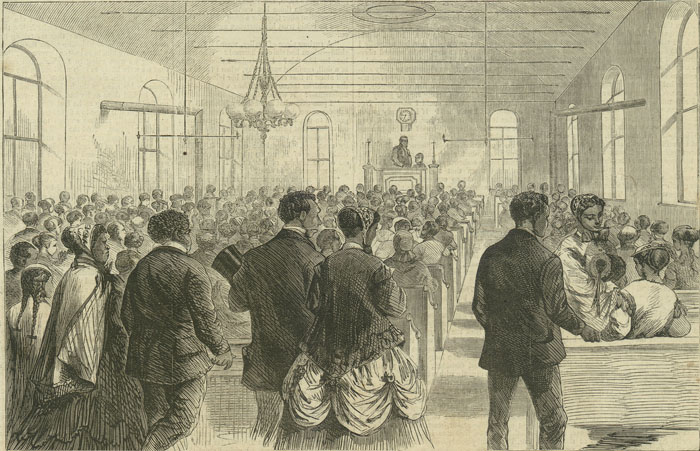

African American leaders throughout the nineteenth century recognized the significance of creating and sustaining national organizations that were built upon local political networks. Central to this was the Black convention movement.1 A survey of the many local, state, and national Black conventions from the 1830s through the 1890s reveals exactly how African Americans sought to defend their rights as American citizens in the public sphere. These conventions were part of a broader political environment of mass meetings – whether formal conventions or community meetings in local Black churches – that provided the necessary space through which Black popular politics could operate in nineteenth century America.

First organized in Philadelphia by free African Americans in 1830, conventions met periodically throughout the nineteenth century. The early meetings focused primarily on the abolition of slavery. However, unlike white abolitionists, Black abolitionists knew that ending slavery was one thing, but for African Americans (both former slaves and those who were free) negotiating a new world without slavery was quite another. As such, these early conventions also argued for equal educational opportunities, land reform, and, in the 1850s, the merits of emigration out of the United States. Even before the end of the Civil War, former slaves had already begun to attend national and state conventions, such as the 1864 national convention that convened in Syracuse, New York . This convention, over which leading Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass presided, led to the founding of the Equal Rights League, an organization that pushed for full political rights. This convention blended together initiatives for political rights and economic improvement with education, and provided a blueprint for subsequent conventions to follow.2

During Reconstruction, the need to secure equal political and civil rights was at the forefront of discussion among conventioneers. Yet by the time white Democrats had regained control of all southern state legislatures, the emphasis of the conventions had moved toward a reliance on self-help and racial solidarity through education and economic advancement. Less studied by scholars, these post-war conventions continued the tradition of the antebellum movement, but within an altered political landscape. As with the pre-war conventions, the debate centered on a number of issues: civil and political rights; economic development; and, in the case of the conference held in Nashville in 1879 , emigration westwards. Responding to the Exoduster movement then underway—the large-scale migration of African Americans who departed the racism along the Mississippi River-states to create a new home in Kansas— former Louisiana Lieutenant-Governor, P.B.S. Pinchback argued that African Americans had to dispel the white myth that the freedmen “have no complaints of murder, violence, intimidation and unlawful deprivation of rights, that all is peaceful and serene, the colored people are happy an simply desire to be let alone.” 3 Ultimately, the conference did not endorse migration; rather it left individuals or communities to decide for themselves whether or not they wanted to leave the South.

While the political avenues open to African Americans in Republican party politics were disappearing by the early 1880s, the convention movement kept Black politics alive in the public sphere. This was especially the case at the next national Black convention, which met in 1883 in Louisville, Kentucky. While not the last of the national Black conventions (the last convened in Cincinnati in 1893), it represented a high-water mark of sorts. In terms of the geographical reach of the delegates, the Louisville convention was the most representative of all the Black conventions. Throughout the summer of 1883, African Americans met across the country in district conventions to select delegates to represent them in Louisville that fall. Some of these local conventions were openly Republican Party meetings; others were not publicly tied to the party.4

In all, representatives from twenty-six states and the District of Columbia packed into the convention hall: out of the 282 delegates present, 243 were from the South. The majority of the delegates were unknown outside of their immediate locality; few of the prominent national Black leaders were present, such as Pinchback.5 The exception to this was the presence of Frederick Douglass, who would be elected as the convention’s chairman. Douglass’ keynote address focused on the importance of African Americans’ securing their economic, civil and political rights. Yet Douglass’ address was aimed as much at white Americans outside of the convention hall as it was at the Black delegates before him. “Though we have had war, reconstruction and abolition as a nation,” he told his white audience, reminding them of slavery’s legacy; “we still linger in the shadow and blight of an extinct institution. Though the colored man is no longer subject to be bought and sold, he is still surrounded by an adverse sentiment which fetters all his movements.” The only way to overcome this, Douglass argued, was for African Americans to be politically engaged, and for white Americans to accept the right of African Americans to vote and to hold political office.

The resolutions approved by the convention followed Douglass’ lead. Among the resolutions passed, the convention called for African Americans to defend their civil rights through the courts; they called on Congress to provide $7 million for southern public education; and they called for a Congressional committee dedicated to the issue of southern labor to go on a fact-finding mission. The conventioneers believed that the answer to labor inequalities in the South lay with encouraging northern investment in southern farms, which in turn would provide further job opportunities for African Americans, who would then in turn possess resources to buy their own farms. The conventioneers also wished to see equal wages for both Black and white Americans become a reality.6

How representative were conventions like the one held in Louisville? The national convention movement was elitist by virtue of the class of African American men who attended. One delegation from northern Alabama, for instance, was made up exclusively of local Black educators. While Black men controlled the debates and made the decisions, this did not stop Black women from attending. Black conventions were not only social occasions for the family, but African American women took an active role in them. Their work in these conventions was gendered, however. At the state convention held in Omaha, Nebraska to select delegates to Louisville, women organized picnics and the entertainment. Women sat with the delegates but no evidence has been found that they had a vote.7 All of this demonstrates the conventions’ broader impact within the Black community. As Elsa Barkley Brown points out, how Black men voted, and what they said in public, mattered to the family unit as a whole; in other words, their actions had significance beyond themselves as individual men.

The Louisville convention reveals that Black political organizing did not cease with Reconstruction, nor was a predominantly Northern-based. Indeed, a consensus is emerging among historians that Reconstruction did not come to a definite end in 1877. Black political activism did continue in the South beyond the “Compromise of 1877,” which saw the Republican Rutherford B. Hayes win the contested presidential election of 1876 in return for a promise to withdraw the remaining federal troops in the South. A focus on black politics in the 1880s reveals the varied strategies used by African American leaders in the South to maintain their political voice in the public sphere, either within or beyond the Republican Party. Not least, African Americans in the South would contribute to the broader debate in the mid-1880s over the very meaning of civil rights, at a time when the debate was widely termed the “Negro Question” or the “Southern Question,” not the “Negro Problem” as it would become in the minds of whites. As Shawn Leigh Alexander has documented in his excellent An Army of Lions: The Civil Rights Struggle Before the NAACP, New York newspaper editor T. Thomas Fortune played a leading role from the mid-1880s onwards in generating support for a national civil rights organization – the Afro-American League – that built on the heritage of the earlier convention movement.

A study of the post-war Black conventions reveals therefore not only the continuation of a key political forum for Black leaders in nineteenth-century America, but also alerts us to the importance of the changing political landscape during the “long” Reconstruction, and the continued efforts of African Americans to maintain their voice in the public sphere. As Douglass argued at the Louisville convention, African Americans were “bound by every element of manhood to hold conventions, in their own name, and on their own behalf, to keep their grievances before the people and make every organized protest against the wrongs inflicted upon them within their power.” At a time when the Republican Party was moving away from its commitment to the rights of all Americans, African Americans were reminding the party, and the nation at large, of the work that remained to be done.

- This piece is based on the author’s research on nineteenth century Black politics. He draws on a range of secondary sources (click the links to access them) and primary sources, including material available on the Colored Conventions Projects website, founded and hosted by the University of Delaware. ↩

- For more on the antebellum convention movement, see Patrick Rael, Black Protest and Black Identity in the Antebellum North (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002). Also see the Colored Conventions Projects website ↩

- Quoted in Nell Irvin Painter, Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas after Reconstruction (New York: W.W. Norton, 1979), 221. ↩

- People’s Advocate, August 18, 1883; Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, Shadow and Light: An Autobiography (1902; reprinted Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 175-78; New York Globe, August 25, 1883. ↩

- Louisville Courier-Journal, September 25, 1883. ↩

- People’s Advocate, October 6, 1883. ↩

- People’s Advocate, August 18, 1883. ↩