Surviving Slavery: Contests Over Bondage in Berbice

Surviving Slavery in the British Caribbean concentrates on the question of agency, whereby narratives of life on plantations in Berbice unsettle standard histories of bondage within the British Caribbean. These queries of individual agency have been central to the work of Walter Johnson, Vincent Brown, Kevin Dawson, and Brooke Newman in recent studies on commodification, necromancy, water cultures, and legal rights under slavery. Randy Browne follows a similar line of questioning, offering discussions of agency grounded in the studies of Julius Scott, to show how enslaved people lived underneath structures of slavery, often in contest with each other, rather than as either a romantic underclass or facing the childlike confines of social death.

Accessing little-used documents from the fiscal for the period 1819 to 1834, Browne describes British slavery in Berbice through the petitions the enslaved used to critique the system. This examination portrays a form of slavery that was much more akin to Spanish structures defined through the Tannenbaum Thesis than the harsh legal controls that defined most of the American South. Using the fiscal office as his central resource, Browne applies James Scott’s ideas of cultural resistance to also explore how different plantation environments often involved many intracommunity contests for power.

The official responsibilities of the fiscal, which included many different legal protections, were known to enslaved people who often negotiated much within their own communities, with masters and overseers, and with different drivers. Because of this focus on enslaved voices, Browne highlights that his work is intended to be unromantic. Rather, this is a tale of mixed motives that moves betwixt categories of race, class, and gender. For example, the cases of individual obeah practitioners and their contests for power within the slave community often left masters choosing skillful captives as community leaders from a contested rather than subdued population.

Browne starts with a narrative of Berbice as the colony transitioned from Dutch to English rule slowly over the late eighteenth century, fully in British hands by 1803. Defining the inherited economic situation through sugar, rising capitalism, and goals of survival, Browne relays how earlier Latin and Dutch traditions were retained in British systems that were quickly moving to broader questions of amelioration. The significant Black majority in the wet, riverine, and diseased colony faced changes as these new customs shifted the role of the fiscal and created more public forms of punishment. Economic crisis during the early nineteenth century also altered supply and demand for the sugar colony, creating even greater impetus for interventionist amelioration from the British metropole.

The second chapter takes up this question of how punishments were slowly shifting from private whippings, which could be influenced by anger, to the depersonalized public punishments of a newly gazing state apparatus that hoped to improve the conditions of slavery. This public alteration involved many punishments upon the treadmill rather than at the hands of masters, overseers, and drivers. Even as a part of amelioration, these new forms of abuse did not supplant slave’s previous rights to petition the fiscal. Questions of trust were always imperative within these appeals, as the fiscal could effortlessly believe enslaved people voiced counterfeit concerns. With these many questions of truth and power it is possible, as Browne surmises, that seventy percent of complaints to the fiscal failed. The shame of having a report at the fiscal could hurt the reputation of an abusive slaveowner, but it seems most avoided punishment even when exceeding the law.

Centering on a relatively understudied topic for chapter three, Browne focuses on the lives of drivers. As victimizers and victims—in the attempt to garner more labor from fellow captives—drivers negotiated within their communities through the power of both the whip and their ability to navigate through the application of less directly violent punishments. Browne is careful with his documents here, as he notes that cases at the fiscal were probably anomalous, as relatively successful drivers were seemingly able to ameliorate discontent prior to petition.

Browne moves next to discussions of gender, as the records of the fiscal provided many marital disputes and arguments between different complainants regarding the rights of women. Often imposing a similar patriarchal order as British masters and the goals of nineteenth century gender relations to create nuclear families, enslaved men in Berbice frequently went to the fiscal to assert their rights over women’s bodies. The multiple oppressions upon enslaved women involved cultures of rape from both masters and other enslaved people, and included nearly unlimited forms of domestic violence, which could be appealed to the fiscal, but rarely involved much personal improvement for the suffering slave. In order to navigate these oppressions, women invented multifarious rumor networks, even as many cases involved women attacking each other over infidelities and for rights to powerful men within the community.

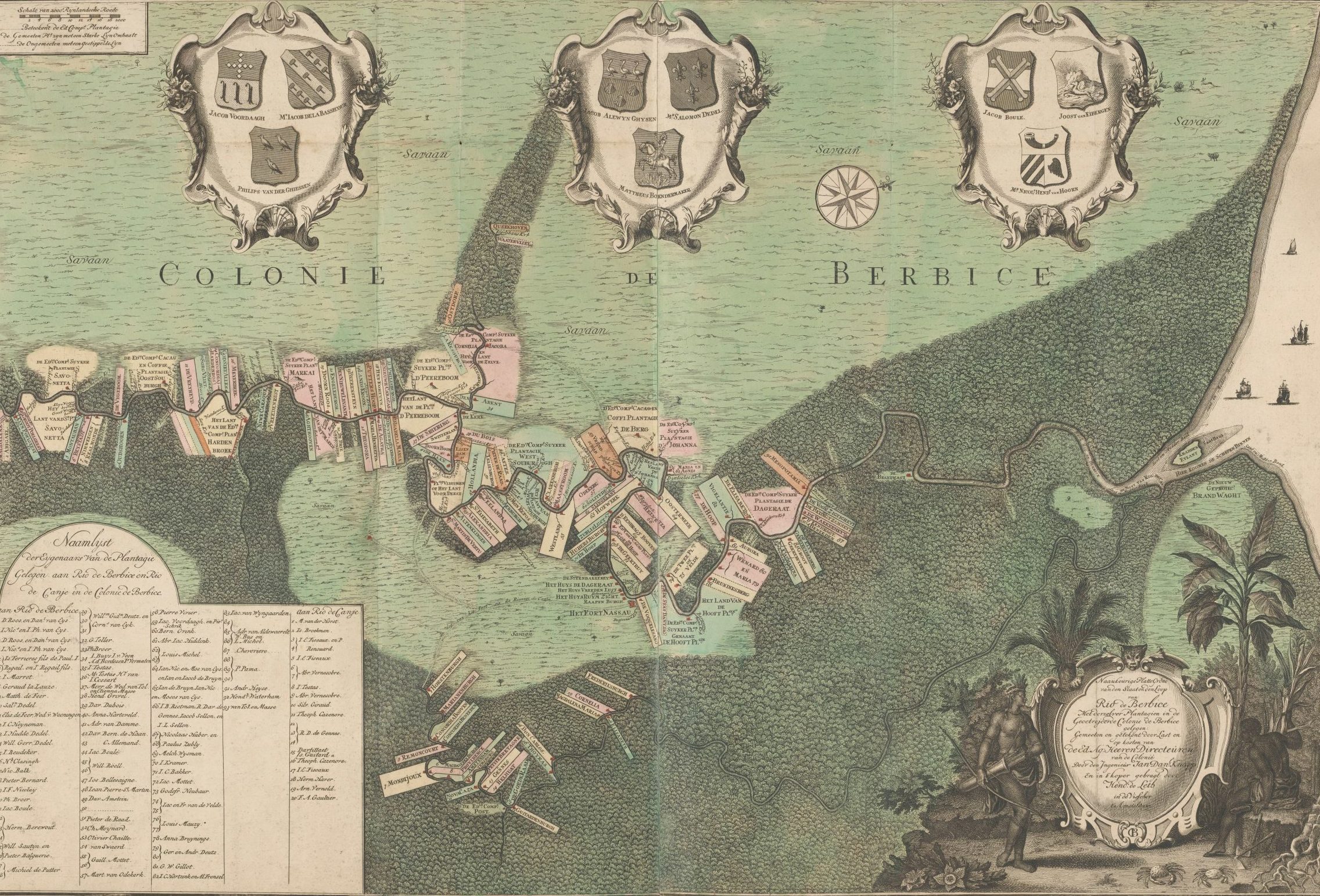

The standout fifth chapter looks upon obeah as a creolized spiritual practice that represents many similarly intricate negotiations within the slave system of Berbice. These practices, especially of the Water Mama, often involved intensely organized hierarchies of power among those in bondage. Obeah, a spiritual system that Browne classifies as more Caribbean than African, would be permitted by enslavers and the colonial state to support calmness of the enslaved community. However, when the monopoly on violence shifted from white hands to Black, crackdowns on leading obeah practitioners began. The use of specific obeah cases highlights Browne’s great attention to the lives of individuals in the colony, as with his extensive use of names in the monograph’s detailed index. The long image descriptions in Surviving Slavery also stand out in this context, whereby the use of illustrations involve deep intellectual dives into the aesthetics, publications, and constructions of the chosen prints.

As the final chapter outlines, these vast negotiations regarding survival created diverse moral economies throughout much of Berbice. Agency once again becomes central here, as Browne describes how the enslaved consistently used the fiscal, and other informal agencies, to defend their rights to be materially supported by their enslavers, own property and provision grounds, and bargain with slave holders for different rights. In part engaging a debate on slavery, proto-capitalism, and capitalism, Brown describes how the fiscal supported rights to clothing, food, private property, and in support of trade, not as any desire to protect the slave community, but seemingly to ameliorate the revolutionary impetus through providing enough material rights to keep enslaved people’s quarrels in legal spaces rather than in revolutionary fields of the machete. Specific examples of failed mortgages and the resistance of enslaved people to mass sales when plantations collapsed highlight a critical chapter regarding the function of a highly capitalized economy.

Browne defines Atlantic slavery through the concept of survival, whereby the essential question for the enslaved was how to endure in the face of harsh labor regimes, unforgiving climates, and punishments from their masters. The general critique that has arisen with Browne’s stellar and often paradigm disrupting work on agency within Atlantic slavery is whether the study can be applied beyond Berbice for this short period of documentation. It is plausible that Browne could have done more to anticipate this assessment, especially concerning similar spaces that once had Dutch legal systems and then altered into forms of British slavery. One important aspect of this assessment seems to be that Browne provided no significant engagement with questions of slavery in New York City, which also seems to have provided more rights to enslaved populations in the wake of Dutch systems. Often, broad queries also arise regarding the nature of education, whether the enslaved were following European traditions within their legal petitions, and the implications of the staples thesis, whether sugar is inherently a product that creates more agency within slave systems. Generally, Browne is reluctant to use Berbice as a telling example regarding these questions and more broadly for categories of race, class, and gender throughout the Atlantic littoral.

In a short epilogue, Surviving Slavery engages some of these broader questions while implicitly concluding that most attempts to use microhistories as telling examples cannot provide the complexity of local spaces enough to be of great value. While quickly noting that the American South is quite anomalous regarding slaveholder’s ability to deny legal rights, Browne does situate Berbice through a more Iberian frame whereby enslaved people could petition much more than throughout the Anglo-Atlantic. Even with a general lack of explicit connection to other regions or structural theory, Browne’s study is exemplary, and always careful, concise, and clear.

This is consequently archival work of the highest order and includes a diligence exemplified through an appendix of representative cases studies and a significant section of endnotes with many discursive implications. The level of precision throughout the work, and the desire to situate Berbice as a local study, may inhibit Surviving Slavery for broad use for other academics. Nevertheless, if scholars are willing to engage the complex questions of agency within Browne’s analyses, they will find great treasure for comparative and structural analysis regarding nearly all spaces of the Atlantic World.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.