Race, Comics, and the Black Intellectual Tradition

In 1990, comics writer Dwayne McDuffie brought the character Deathlok, a cyborg, back to the pages of the Marvel Universe. Before Deathlok, McDuffie penned issues of Damage Control, Captain Marvel, and Avengers Spotlight. McDuffie’s incarnation of Deathlok differed from earlier iterations in the 1970s and 1980s that focused on former soldiers such as Luther Manning becoming the Deathlok cyborg, a weapon of the US government. McDuffie still has Deathlok serving a military role, but the focus shifts from white soldiers such as Manning to Michael Collins, a Black professor. In a four-issue mini-series in 1990, Collins, a pacifist working for Roxxon Oil, becomes Deathlok after his boss, Harlan Ryker, sedates him and transplants his brain into the Deathlok cyborg. As Deathlok, Collins fights revolutionaries who oppose Roxxon Oil’s operations in the fictional South American country Estrella. Collins gains control of the Deathlok cyborg, commands it not to kill, and sets out to find his human body. After the mini-series, McDuffie and artist Denys Cowan took the reins of a monthly series in 1991.

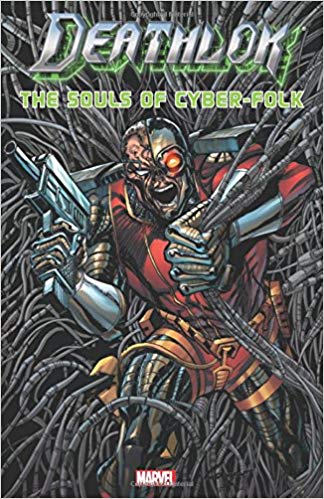

Issues 2 through 5 of the series draw upon a Black intellectual tradition, as the title of the run, “The Souls of Cyberfolk,” demonstrates. Through the character of Collins, McDuffie challenges stereotypes about Black life in America. McDuffie crafts Collins as a successful engineer, devoted family man, and a pacifist. With Collins, McDuffie highlights the importance of representation, especially in a field that produced Blaxploitation-esque characters such as Luke Cage and Black Lightning in the 1970s.1 As such, when speaking about the creation of Milestone Media, McDuffie told The Plain Dealer:

If you do a black character or a female character or an Asian character, then they aren’t just that character. They represent that race or that sex, and they can’t be interesting because everything they do has to represent an entire block of people.”

Journalist and comic-book writer Evan Narcisse asked McDuffie in 2010 about Collins’s riffing on W.E.B. Du Bois. McDuffie responded by stating, “Invisible Man was, and still is, my favorite novel. I’d just read The Souls of Black Folk and was explicitly thinking about Skip Gates’ The Signifying Monkey. Godel, Esher, Bach, and Derrick Bell’s dialogues about race and law sort of crashed in my head. Deathlok was a way of sharing some of my thoughts about all of this.” McDuffie’s comments clearly highlight the Black intellectual tradition that he was working within during his tenure at the helm of Deathlok. The incorporation of discussions of identity with the integration of Du Bois created a space for Black readers to identify more closely with Collins but also as a way for white readers to think about race and identity.

“The Souls of Cyberfolk,”clearly drawing upon DuBois’s The Souls of Black Folk, features Deathlok, Misty Knight, the X-Men, and the Fantastic Four fighting Mechadoom, a Doombot seeking to gain independence from Dr. Doom. The conversations between Collins and Misty Knight, a Black private detective with a cybernetic arm, carry on a Black intellectual tradition for readers in the same way that hip hop artists do for listeners, and, as Lysa Rivera notes, “emphasizes a compelling metaphorical alliance between cyborg consciousness and African diasporic experience.”

In “The Souls of Cyberfolk,” Misty Knight recruits Deathlok to help her figure out why some superheroes have disappeared. At first, he is apprehensive, but once he finds out that Misty Knight is a cyborg as well, he finds a kinship with her and opens up to the idea of assisting her. According to Misty Knight, “Cybernet refers to anybody who is either a cyborg or a sentient robot. Cybernetic organism or cybernetwork;” thus, both Deathlok and Misty Knight are “cybernets.” Misty Knight’s comment moves the conversation towards an exploration of the power of language and its ability to control and subjugate.

The movement towards “cybernets” allows McDuffie to address issues of language while maintaining reader investment, specifically white reader investment. Their conversation makes clear that the underlying subtext is that McDuffie is commenting on other terms of subjugation and oppression. Misty Knight elaborates by saying, “It’s a term of derision. Co-opted by some of the more politically minded members of our little demographic. If we make it our own, it takes the sting out of anyone using it to describe us.”

The movement towards “cybernets” allows McDuffie to address issues of language while maintaining reader investment, specifically white reader investment. Their conversation makes clear that the underlying subtext is that McDuffie is commenting on other terms of subjugation and oppression. Misty Knight elaborates by saying, “It’s a term of derision. Co-opted by some of the more politically minded members of our little demographic. If we make it our own, it takes the sting out of anyone using it to describe us.”

The term “cybernet” highlights the power that language has to shape, control, and oppress. While initially “a term of derision,” some “cybernets” have taken it and have tried to make it their own. Following Misty Knight’s comments, Deathlok drives the point home by stating, “Control the language control the terms of the debate.” This is nothing new. Linda Thuhiwai Smith notes that “indigenous peoples, people ‘of colour,’ the Other, however we are named, have a presence in the Western imagination, in its fiber and texture, in its sense of itself, in its language, in its silences and shadows, its margins and intersections.”

As the conversation continues, Collins thinks about a letter that he will write to his wife Tracy, telling her that he does not feel afraid of Misty Knight, and ultimately, “the prospect of meeting other cyborgs of talking to people who have already been through the same things I’m going through now . . . well, that’s just too good an opportunity to pass on.” In this moment, Collins comments on the importance of representation and community. He feels connected to Misty Knight, even though they come from different backgrounds, due to their shared experiences as cyborgs.

Collins’s connection to Misty Knight can be read literally as Collins connecting with the private detective because they are both cyborgs. On another level, it must be read as a commentary on race and class. No matter what class status Collins obtains as an engineer, society will treat him differently because of his skin color. Regardless of Misty Knight’s background, the hegemonic society treats her differently for the same reason.

The conversation concludes with Collins telling Misty Knight that he does not want her to call him Deathlok. Rather, he says, “My name is Michael,” and Misty Knight obliges. Collins’s assertion of his identity also serves as his assertion on language and the power that it yields. Instead of succumbing to the label Deathlok, Collins places his humanity at the forefront through his insistence that Misty Knight refer to him as Michael. He will not let others define him or label him because if he does then those people will “control the terms of the debate.”

After their initial conversation and a car chase, Collins and Misty Knight speak about identity again in her apartment. Here, Collins quotes Du Bois verbatim. By having this scene immediately after the initial conversation in the car, McDuffie places the emphasis on how Collins and Misty Knight navigate a world that considers them not just as cyborgs but as Black individuals in America.

While wrapping up Misty Knight’s arm, Collins sees a framed picture of her partner, Colleen Wing. He asks her if she trusts Colleen, to which she responds, “I trust her more than I trust myself. She’s like a sister to me. It’s just that this cyborg stuff is . . . look, this is embarrassing, can we skip it?” Collins proceeds to inform her that before he became “this thing,” he was Black, and in college, he had a white friend; however, “there were places our friendship couldn’t go.” Rather than focusing on cyborgs or cybernets, the discussion moves towards race, away from allegory and into the realm of reality. Comics veteran Joseph Illidge points out that through his stories, McDuffie created comics where “the cultural demographics closely mirrored those of the real world.”

McDuffie achieves this by having Misty Knight and Collins talk about their Black identity. This movement draws a link between the cyborg allegory and the world outside of the pages that the reader inhabits. In both instances, the consensus becomes that Collins’s and Misty Knight’s identities do not originate from themselves; they originate from the labels that others place upon them. Collins counters this when he tells Misty Knight to call him Michael instead of Deathlok.

Throughout “The Souls of Cyberfolk,” and the series as a whole, Collins struggles to find his identity and his true self. Others label him “monster,” “cybernet,” or “cyborg,” but he works to maintain his true self through his one-sided epistles to Tracy and through his interactions with Misty Knight and the computer he inhabits. Through Deathlok, and other comics such as Milestone’s Hardware, Icon, Static, and more, McDuffie infused the medium with representation and became part of the Black intellectual tradition that he drew from. As Derek Dingle noted upon McDuffie’s untimely death in 2011, “Dwayne realized the importance of creating such images because they represented heroes and opportunities.”

- McDuffie, Denys Cowan, Michael Davis, and Derek T. Dingle founded Milestone Media in 1993. Milestone Media worked to bring greater representation to comics through the creation of characters such as Hardware, Icon, and Static. ↩