Prophets and Religious Radicals: An Interview with Albert Raboteau

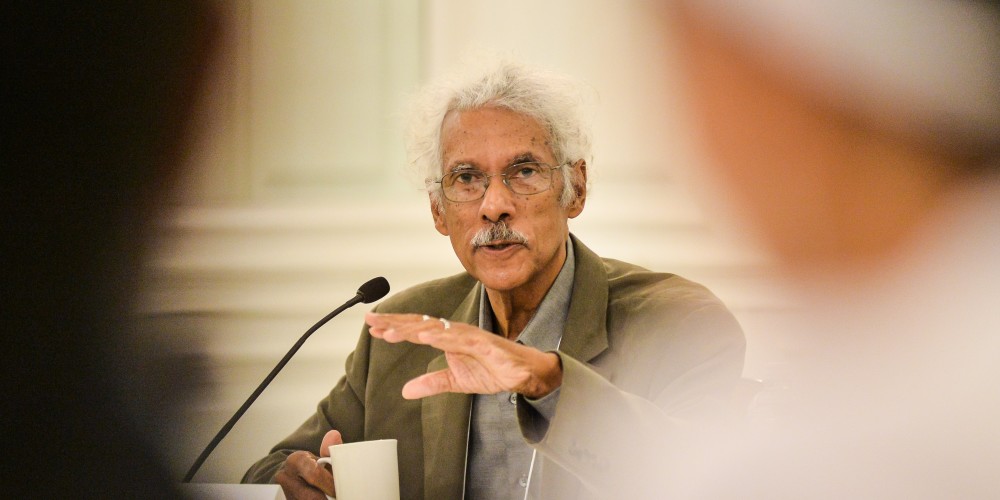

This month I had the opportunity to interview Albert J. Raboteau about his new book, American Prophets: Seven Religious Radicals and their Struggle for Social and Political Justice. Published by Princeton University Press, American Prophets “sheds critical new light on the lives and thought of seven major prophetic figures in twentieth-century America whose social activism was motivated by a deeply felt compassion for those suffering injustice.” Raboteau, a specialist in American religious history, is the Henry W. Putnam Professor of Religion Emeritus at Princeton University. His research and teaching have focused on American Catholic history, African-American religious movements and currently he is working on the place of beauty in the history of Eastern and Western Christian Spirituality. He has written several books including Slave Religion: The ‘Invisible Institution’ in the Antebellum South, and A Fire in the Bones: Reflections on African-American Religious History.

Cameron: You note early in the book that the work developed out of the Religious Radicals course you taught at Princeton. Can you talk about how teaching this course influenced your writing of American Prophets?

Raboteau: I taught this seminar 5 or 6 times at Princeton. It was very useful because I had the students do pretty extensive reading about many other figures who are not included in the book. From their reactions, I was able to tell which authors seemed to strike them the most. A number of people have asked me why I chose these seven. In part, the students are the ones who helped me to decide. For example, several readers have asked me why I didn’t include Cesar Chavez. My answer was that students didn’t respond as well to him. Chavez wasn’t a particularly eloquent speaker so there wasn’t as much for them to grab hold of in terms of his speeches and he wasn’t much of a writer either. Students helped me by choosing the religious radicals who were most meaningful to them. That was one of their contributions to the book, as well as their responses to those who did wind up in the book.

Cameron: In any book you have to make tough decisions about what and whom to include or exclude. How did you decide to focus on the seven figures in this text? And what makes them prophets?

Raboteau: These seven–Abraham Joshua Heschel, A. J. Muste, Dorothy Day, Howard Thurman, Thomas Merton, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Fannie Lou Hamer–seemed to me to articulate in their lives and their writing or speaking the essence of Abraham Joshua Heschel’s definition of the prophet as one who feels in his or her bones the divine pathos for humanity and is compelled to express it. Each had a major social impact through their expression of compassion for the poor and oppressed and led significant numbers of Americans to join movements for social and political change. What Heschel’s definition of the prophet does is enable us to see how people come to an understanding that they have the duty to identify with the oppressed–those who are suffering. To identify with them not just as a sentiment like “oh, that’s too bad” but feeling with them, often through a conversion experience of some sort. They begin to feel the need to share in the lives of these people and to do something about their situation. So they were led to a more radical action than those of us who say “that is too bad, I wish there was something I could do about it.” These are people who are actually driven to action. And so their lives are not only exceptional, but also exemplary.

Heschel’s notion of feeling the divine pathos for humanity makes two contributions. One is that it reinforces or strengthens the providential understanding of God. One of the primary texts for that would be the Exodus. But another primary text is from Isaiah, which is that “I am anointed to preach the good news of salvation to the poor and to lift up the oppressed and the needy.” So those two texts became leitmotifs in the lives of these seven people and that is what I think makes them prophetic. Heschel’s notion that they feel the divine pathos for humanity as if it were a fire in the bones means that they were impelled to speak about that fire. They experienced an inner compunction that drove them toward action and hence the proliferation of movements they were involved in–civil rights, peace, antipoverty.

All these movements have their source in the prophetic identification with God’s involvement in humanity. A. J. Muste said something that was really amazing to me and it would be accurate to say a number of these figures had the same opinion. What he said in a small essay he wrote that circulated among activists going to Mississippi for Freedom Summer was “as we all know, unmerited suffering releases the divine power in human history.” The concept that unmerited suffering is redemptive was held by a number of radical black thinkers like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Fannie Lou Hamer. That takes a real act of faith to accept, but it is part of their prophetic stance. It is what gave them courage. When Fannie Lou Hamer said “I’ve been anointed” she displayed her sense of calling as an identity that has to be obeyed, all of which served to make these people prophets.

Cameron: All the thinkers you examine in the book espouse some form of providentialism, or the belief that God is intimately involved in earthly affairs. Do you see this as an essential component of prophecy and religious radicalism?

Raboteau: Yes, I believe that their faith in the biblical narratives of Exodus, prophecy, and redemptive suffering, were essential for their construction of an alternative script to the hegemonic cultic piety of the nation. Providentialism as a significant force in black religious history stretches back to Olaudah Equiano in the late-18th century. It is a sense that God is active in human history at large but also in an individual’s personal history. That is to adopt a script which is often contradictory to the dominant hegemonic script of the nation. If this is the New Israel, why is it that all of us aren’t free? America will be the old Egypt until all of God’s children are free, they argued. So you have this counter use of the Bible for myths that contradict the national myth.

In 1774, slaves in Massachusetts wrote a petition to the General Court that mentioned that just as whites were fighting for their freedom from Great Britain, so too are slaves asking for their freedom. They also asked how it could be that they gave up their freedom by no compact whatsoever and were made slaves in the bowels of a Christian nation. So even as early as the 18th century, African Americans were denying both the civil script that this is a land of freedom and opportunity and also the biblical script that tends to be used to identify the nation as a New Israel. Thus two Christianities were formed in this nation and also two different notions of what the destiny of the country is–one coming from the slaves and the other coming from the slaves’ masters and others who supported slavery. As an alternative script these passages from the Bible become extremely important as contradictory scripts for black people in the country.

Cameron: In chapter 6 you note of Martin Luther King, Jr. “We must remember that King, as he frequently noted, did not make the movement, rather the movement made King.” In thinking about today’s contemporary movement for civil rights, Black Lives Matter, what do you see to be its major influence on African American religion and how are black religious leaders in turn shaping the movement?

Raboteau: A number of the leaders of Black Lives Matter as it began to emerge out of the various shootings that have taken place at the hands of police in different locales are women ministers and so part of what is interesting about this movement is that it is religious in that there are people who are religious who are connected with it, with churches serving as meeting spaces and sources of support and activism. But what is different is that it is not yet an organization. It remains to be seen whether or not it will become an organization or remain a loosely knit group of movements in various parts of the country.

It is also much more similar to Ella Baker’s notion of leadership rather than MLK and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)’s notion of leadership. This is not the dominant black male preacher who is in charge. It is a more loosely organized structure with a variety of people, none of whom are in charge but some of whom are spokespersons and have positions that are more from the ground up. So I think it is the position of the male clerical leader epitomized by the SCLC and King that is consciously not being followed by members of this movement.

Cameron: Throughout the book you posit that we can both learn from and be inspired by the seven figures you discuss. What would you like readers to take away from reading American Prophets?

Raboteau: I hope that readers would take away the important lesson that these figures were not simply exceptional but they were also exemplary. That is we should be moved to imitate their compassion and activism on behalf of those in our society who suffer neglect, oppression, and poverty. They should inspire us to continue the struggle against the “evil triplets” of militarism, racism, and extreme materialism that continue to mar our society.

Chris Cameron is an Associate Professor of History at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. His research and teaching interests are in African American and early American history, especially abolitionist thought, liberal religion, and secularism. His first book is entitled To Plead Our Own Cause: African Americans in Massachusetts and the Making of the Antislavery Movement (Kent State University Press, 2014). Follow him on Twitter @ccamrun2.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.