On James H. Cone and Black Humanity

*This post is part of our online forum on the Life and Legacy of Dr. James H. Cone.

As an undergraduate student, I took an independent study course on the complexities of Black leadership. I intended to explore the varying strategies and styles African Americans employed to actualize their freedom. To gain the full recognition of their humanity, I pondered, what actions did African Americans take to make their existence in America real and meaningful in the face of holistic disenfranchisement and the violence used to enforce it?

In hindsight, I engaged the material a bit too confident about the history that I thought I knew and understood. I knew that there were leaders, but I had not yet grasped what the nuances of leadership meant, or how important grassroots organizing was to the Black Freedom Movement. My crude understanding of the movement was a straightforward tale of right and wrong where the lines of courage and faith were fixed. There were no gray areas for me. In my mind there were only two sides: peace loving integrationists who I deemed as weak and nationalists whose leadership I viewed as radical, righteous, and most importantly, strong. All of that would change with my introduction to James Cone’s work.

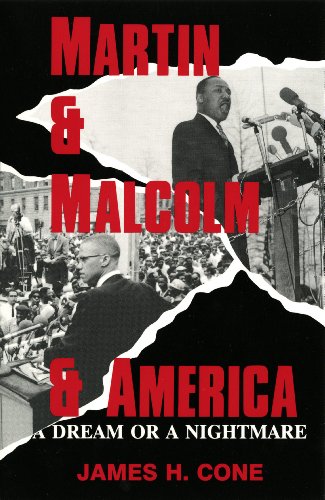

I was assigned to read James Cone’s Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare (1991) for my independent study. The title captured my attention, but the content led me to change my mind: it was a seismic paradigm shift. Prior to reading the book, I thought oppression required a bold declaration of uncompromising justice in the face of oppressive, dehumanizing power with no room for compromise or nuance. Cone forced me to think deeper. Cone explained the importance of Vincent Harding’s “Great Tradition of Black Protest,” as “a tradition that comprised many variations of nationalism and integrationism. Martin and Malcolm’s perspectives on America were influenced by both, even though they placed primary emphasis on only one of them.”1 The text forced me to re-examine and deconstruct my beliefs about leadership that initially led to the view that integration and nonviolence were antithetical to a successful movement for civil rights. With a new framework from Cone to understand charismatic and grassroots leadership there was now room, in my evolving mind, for the coexistence of both approaches and the various strategies each deployed within the Civil Rights Movement.

I was assigned to read James Cone’s Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare (1991) for my independent study. The title captured my attention, but the content led me to change my mind: it was a seismic paradigm shift. Prior to reading the book, I thought oppression required a bold declaration of uncompromising justice in the face of oppressive, dehumanizing power with no room for compromise or nuance. Cone forced me to think deeper. Cone explained the importance of Vincent Harding’s “Great Tradition of Black Protest,” as “a tradition that comprised many variations of nationalism and integrationism. Martin and Malcolm’s perspectives on America were influenced by both, even though they placed primary emphasis on only one of them.”1 The text forced me to re-examine and deconstruct my beliefs about leadership that initially led to the view that integration and nonviolence were antithetical to a successful movement for civil rights. With a new framework from Cone to understand charismatic and grassroots leadership there was now room, in my evolving mind, for the coexistence of both approaches and the various strategies each deployed within the Civil Rights Movement.

It is rather impossible to address the impact of James H. Cone in the space I am allotted in this very special and needed forum. When considering his contributions to the field, the word genius is too simplistic a term to encapsulate the transformative influence of Cone’s intellections because his work went beyond the disciplines of theology and religious studies and had a broader influence on fields such as African American History.

As a historian I find a particular inspiration and strength in Cone’s writing. His work is informed by history yet grounded in a spirit that seeks to affirm Black humanity while speaking to the inherent contradictions of liberty in America. While Cone was not the first to articulate the importance of Black humanity in the throes of white supremacy, he is without question aligned in the righteous legacy of Black intellectualism, from David Walker’s Appeal to Assata Shakur’s autobiography and beyond.

His 1969 treatise, Black Theology & Black Power is heralded as his seminal work. Critically, one does not need to be steeped in a Judeo-Christian ethos to understand, appreciate, and respect the scope and the gravity of his influence. Black Theology & Black Power is a text I did not read until I was a graduate student trying to make sense of the dissonance that accompanies the journey of being an aspiring academician, conducting research on the state sanctioned violence that accompanies our country’s history, while also being filled with rage of even having such a topic to study. This kind of rage was famously described by James Baldwin as the state of being Black in America: “to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time. So that the first problem is how to control that rage so that it won’t destroy you.”2 In Cone, I found someone who did not let that anger and rage destroy him despite being confronted with it via the subject of his works. On the contrary, he mentioned on more than one occasion that he wrote Black Theology & Black Power, primarily because if he did not write, he knew that he would be consumed by his rage. Cone wanted, “to speak on behalf of the voiceless black masses.”

His 1969 treatise, Black Theology & Black Power is heralded as his seminal work. Critically, one does not need to be steeped in a Judeo-Christian ethos to understand, appreciate, and respect the scope and the gravity of his influence. Black Theology & Black Power is a text I did not read until I was a graduate student trying to make sense of the dissonance that accompanies the journey of being an aspiring academician, conducting research on the state sanctioned violence that accompanies our country’s history, while also being filled with rage of even having such a topic to study. This kind of rage was famously described by James Baldwin as the state of being Black in America: “to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time. So that the first problem is how to control that rage so that it won’t destroy you.”2 In Cone, I found someone who did not let that anger and rage destroy him despite being confronted with it via the subject of his works. On the contrary, he mentioned on more than one occasion that he wrote Black Theology & Black Power, primarily because if he did not write, he knew that he would be consumed by his rage. Cone wanted, “to speak on behalf of the voiceless black masses.”

Cone’s ability to link the lived experience to the imagination of the present and, most importantly, to conceive of a bright new future is the true legacy of his work. In The Spirituals and the Blues, for instance, Cone provides an important intellectual testimony to the historical power and dynamism of Black folklife through the “the power of the song in the struggle for Black survival—that is what the spirituals are all about.” Cone heard the sacred and secular songs from the juke joints and churches and argued that both were essential to identity and survival in his beloved Bearden, Arkansas. “Black music is a living reality,” Cone affirmed. “And to understand it is necessary to grasp the contradictions inherent in black experience.” In that vein, his understanding of the coexistence of the sacred and secular allowed me to experience music differently, too. I heard Notorious B.I.G.’s “Everyday Struggle” or Tupac’s “Shed So Many Tears” and was able to reconcile them with Mahalia Jackson’s recording of “How I Got Over” as well as congregational hymns like, “Come and Go to That Land.” Cone’s analysis illuminated the critical importance of cultural expression and the interdependent relationship between the sacred and the secular. It is yet another example of how he helped reclaim Blackness from the dehumanizing erasure of white supremacy.

In the final analysis, James Cone facilitated a compelling and powerful way for African American scholars, artists, and everyday folk, to proudly write about and celebrate the breadth of their lived experiences beyond its relation to pain and suffering as it is so often described. Rather, Cone captured the many ways that African Americans have profoundly shaped the lived experience of all Americans in the face of systematic oppression while simultaneously seeking restorative justice.

Reflecting on the Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky’s assertion that he be “worthy of his suffering,” Cone soberly declared, “There is only one thing I dread…not to be worthy of the life that the suffering of Black people have made possible for me.”3 Though gone, Cone’s voice is anything but silent as his work continues to echo in the scholarship that is produced today.

- James H. Cone, Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1992), 16; Vincent Harding, There is a River: The Black Struggle for Freedom in America (New York: Harcourt Jovanovich, 1981), 83. ↩

- James Baldwin, Emile Capouya, Lorraine Hansberry, Nat Hentoff, Langston Hughes and Alfred Kazin, CrossCurrents, Vol. 11, No. 3 (SUMMER 1961), 205-224. ↩

- Cone, lecture, “Black Theology and Black Power,” 19 April 2017. ↩

Dr Mitchell,

Thank you for reminding us of the tremendous impact Dr. Cone made as an intellectual and theologian. His texts further inspire us to continue our quest toward human-ship while helping us to control our rage within.

Great work Dr. Mitchell! My research also attempts to tackle the complexities of leadership. I came up with a concept I call “Leadership from the Margins Theory” where I use the Haitian Revolution as a backdrop to describe 5 characteristics that I believe marginalized leaders possess.