Nation Time: ‘A Nation Within A Nation’ At Twenty

*This post is part of our online roundtable celebrating the 20-year anniversary of the publication of Komozi Woodard’s A Nation Within a Nation

Komozi Woodard’s foundational work, A Nation Within a Nation: Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Black Power Politics, turns twenty this year. I have lived with it about a decade longer that. I first met author and manuscript, in that order, in 1990 in Evanston, Illinois. Fresh out of graduate school both, we had just arrived at Northwestern University on postdoctoral fellowships. A defining characteristic of the man, evident on first acquaintance, was his generosity, not just of spirit but also of deed. As the bluesmen and women like to say, it can be a mean old world, the academy, which, for all the patina of concert and collegiality, is often replete with selfishness and self-centeredness. As much as anything else, narcissism and self-conceit rule the academic roost. Komozi Woodard is a refreshing rebuke to that mode of existence. He has, in my three-decade experience with him, consistently been a model of selflessness and cooperative work. That is probably not accidental. A historian of the movement, Komozi also came out of the movement, which is why he was able to write the book he did—one brimming with personal insights and recollections. Komozi is a primary source on foot, a living, breathing archive, one that is always available for consultation by all. Small wonder that the author of A Nation Within a Nation became an informant—not to be confused with an informer—of his own book.

And what a book it is. In the realm of scholarship, the U.S. Black Power movement took a drubbing in the 1980s and 1990s when, as the old-time African Americans liked to say, it was “buked [rebuked] and scorned,” allegedly for having disrupted and destroyed the glorious, interracial civil rights movement. Woodard came to refute such hokum. Appearing in the last year of the century, A Nation Within a Nation was a key part of a larger counternarrative to reframe the understanding of U.S. Black Power. If nowadays the Black Power-discrediting nostrums have lost (much of) their sting, it is largely because of the handiwork of Woodard and fellow laborers. That redefining of Black Power is a key component of what Woodard dubs “groundwork,” a word that appears repeatedly in his corpus, not just A Nation Within a Nation.

Broadly, A Nation Within a Nation may be said to have made a twofold contribution: one to history and the other to historiography, that is, to chronicling and interpreting Black Power. The scholarship on U.S. Black Power has long given pride of place to certain organizations, among them the Black Panther Party (BPP) and US Organization (USO), with their West Coast origins. Woodard’s book shifted the focus in multiple ways by centering the national aspirations of the Newark-based movement under the leadership of Amiri Baraka. He summarizes his argument thusly:

Between 1967 and 1972 the politics of black cultural nationalism crystallized in the Modern Black Convention Movement, and Imamu Amiri Baraka sought to establish Newark’s Black Power experiment and its black political conventions as a national prototype for the black liberation movement. In this new paradigm for black liberation, leadership would be accountable to the will of the black assemblies; instead of the media, the black conventions would legitimate black leadership. (92)

This “new paradigm for black liberation” nationally was a work of synthesis, fusing the political and cultural orientations pioneered on the West Coast—orientations stereotypically associated with, respectively, the BPP and USO. In its origins, the Baraka-led Newark movement was much indebted to the West Coast-founded organizations, USO much more so than the BPP. Herein lies the foundation, in part–there was also Baraka’s own background as a poet and playwright–for Newark’s emphasis on the “politics of black cultural nationalism,” which necessarily is also the leading theme in A Nation Within a Nation. But the qualifier—“politics”—is key, since ultimately the “politics of black cultural nationalism” [emphasis added] was what would differentiate the Newark movement from USO’s more unqualified “black cultural nationalism.”

Briefly summarized, such is the contribution of A Nation Within a Nation as a work of history and a chronicle of the Black Power phenomenon in Newark as well as its national implications. Upon publication, the book instantly became the benchmark by which all future studies of its subject matter would be judged. Obviously, Woodard did not write, and could not have written, the last word on the Newark movement. In the future, fuller and more detailed accounts of Black Power in Newark will likely be written, based in part on sources that were not available to the author of A Nation Within a Nation. Those future histories may even draw on Woodard’s personal papers, which surely ought to be deposited in some public archival collection. But a fuller, more detailed, even more factually accurate historical account does not, ipso facto, amount to a better one. In this regard, A Nation Within a Nation may bear some comparison to The Black Jacobins, C. L. R. James’s iconic work on the Haitian Revolution and Toussaint Louverture. Since the appearance of James’s book in 1938, others have written more complete and factually accurate histories of the Haitian Revolution. Even so, Black Jacobins remains without parallel in its conception of the Haitian Revolution and in its placement of that specific event in the larger history of revolutions and revolutionary movements across time and space.

This crucial point, which turns on conception and imagination, leads to the second outstanding feature of A Nation Within a Nation: its interpretation of the larger Black Power movement in the United States. Here, the crucible is Woodard’s notion of the “Modern Black Convention Movement.” Once more the modifier—in this case “modern”—is crucial; that is, modern as opposed to original or classical. And that, precisely, is Woodard’s point: as a tool for organizing, and theorizing, African American liberation on a national scale, Black Power, with Newark in the vanguard, revived a tried and tested political mechanism, the convention movement. Of course, in the African American experience, the convention movement originated in the antislavery struggle, and more particularly in the determination of the nominally free Blacks in the antebellum United States to stake out a vanguardist and autonomous claim in the fight to end human bondage. What Woodard says (in the quotation above) about the Modern Black Convention Movement was also true of its classical, antislavery prototype and antecedent: “leadership would be accountable to the will of the black assemblies; instead of the [white-run, capitalist] media, the black conventions would legitimate black leadership.”

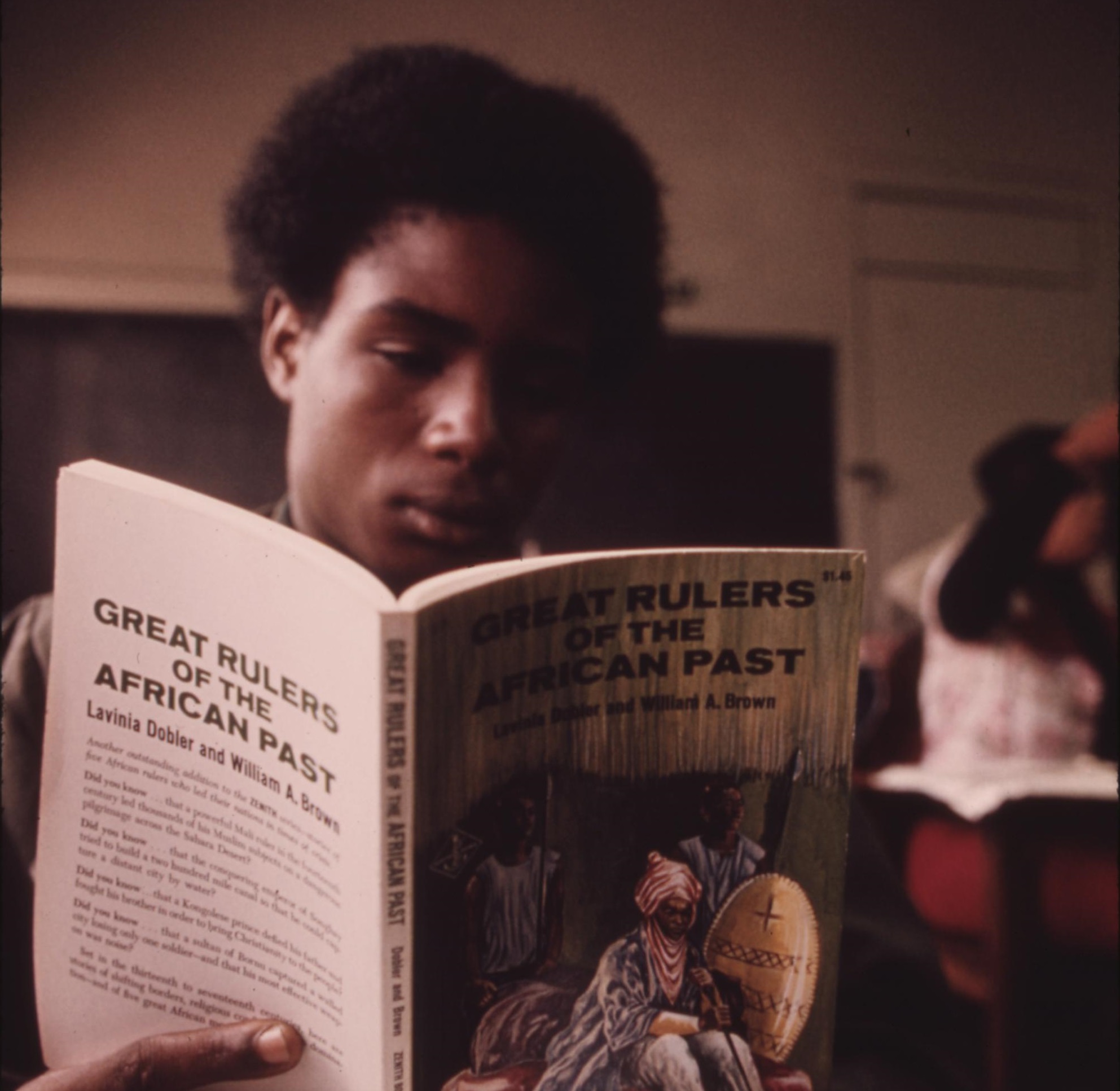

In this way Woodard drew a tight connection, one that is not as well appreciated as it should be in much of the secondary literature, between Black Power and the antislavery struggle. To the author of A Nation Within a Nation, coming as he did out of the movement, such a link was axiomatic: it was routinely made by Black Power activists themselves, in their prose and in their poetry, in their visual and performing arts. No Black Power syllabus—the reading list of recommended texts for movement militants—was complete without material on slavery. Such material included Black Jacobins. As Baraka, in his Marxist-Leninist incarnation, having abandoned cultural nationalism, noted with reproving admiration:

Unfortunately, for all of C.L.R.’s great work, he is still very much influenced by his Trotskyist youth and often counsels people incorrectly, telling them that spontaneous organization by the masses is a substitute for the Leninist vanguard party…But he is still a great historical writer and his books of Marxist and cultural historical theory and his book on Haiti, Black Jacobins, are landmark works.”

The linkage with antislavery was a common theme in the Black Power movement in the Americas more broadly, not just in the United States. One piece of evidence will have to suffice here. That would be the Congress of Black Writers, which was subtitled, “Towards the Second Emancipation,” the first emancipation having been the successful hemisphere-wide campaign against slavery. Held in 1968 in Montreal, Canada, the Congress of Black Writers, to which A Nation Within a Nation should have been more attentive, was the first genuinely international Black Power conclave. In effect, the Congress of Black Writers was a transnational expression of the Modern Black Convention Movement. Its speakers included C. L. R. James. Baraka was also invited in a speaking capacity, but did not make it. Altogether no single work, whether focused on the United States or not, links Black Power to antislavery as powerfully as A Nation Within a Nation.

It is a tour de force, this now twenty-year-old work by Komozi Woodard, a Black Power rock for the ages. Predictably, the book’s concluding sentence recalls the antislavery struggle while also restating the avowed aim of Black Power in its more revolutionary incarnations. Here they are, and they remain as fresh and relevant as when originally penned, the final words of A Nation Within a Nation: “The great people whose ancestors and their allies arose in moral outrage to destroy U.S. slavery will certainly rise again and again until internal colonialism and American apartheid are vanquished” (270).

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.