Migration, Diasporic Self-Making, and Madame De Mena: An Interview with Courtney Morris

In today’s post, Kami Fletcher, an Assistant Professor of African American History at Delaware State University, interviews Courtney Desiree Morris about her recent article in the special journal issue on “Women, Gender Politics, and Pan-Africanism” edited by Keisha N. Blain, Asia Leeds and Ula Y. Taylor. This Fall 2016 issue of Women, Gender, and Families of Color examines the gendered contours of Pan-Africanism and centralizes black women as key figures in shaping, refining, and redefining Pan-Africanist thought and praxis during the twentieth century. This piece is part of a continuing series of interviews with contributors to this special issue. Previously, Kathryn Vaggalis, the managing editor of Women, Gender and Families interviewed guest editor Keisha N. Blain on the origins of the special issue. Azmar Williams also interviewed Ashley Farmer about how African American women forged diasporic relationships and communities. Morris’ essay, “Becoming Creole, Becoming Black: Migration, Diasporic Self-Making, and the Many Lives of Madame Maymie Leona Turpeau de Mena,” describes the origins of Madame Maymie Leona Turpeau de Mena, her central role within the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), and her contributions to Pan-Africanism. The issue is now available in hard copy and online through ProjectMuse and JSTOR. Readers can download the introduction of the special issue here.

Courtney Desiree Morris is an Assistant Professor of African American Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at The Pennsylvania State University. She is currently completing her first book, To Defend This Sunrise: Black Women’s Geographies in Nicaragua. She completed her PhD in Anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin under the advisement of Edmund T. Gordon. Her work has been published in the American Anthropology, the Bulletin of Latin American Anthropology, Women, Gender, and Families of Color, and several edited volumes. Dr. Morris is a regular guest expert on the nationally syndicated radio and television news program, Rising Up with Sonali. She is also a practicing visual artist.

Courtney Desiree Morris is an Assistant Professor of African American Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at The Pennsylvania State University. She is currently completing her first book, To Defend This Sunrise: Black Women’s Geographies in Nicaragua. She completed her PhD in Anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin under the advisement of Edmund T. Gordon. Her work has been published in the American Anthropology, the Bulletin of Latin American Anthropology, Women, Gender, and Families of Color, and several edited volumes. Dr. Morris is a regular guest expert on the nationally syndicated radio and television news program, Rising Up with Sonali. She is also a practicing visual artist.

Kami Fletcher: Please provide a brief introduction to Madame Maymie de Mena for readers who might be unfamiliar with this black woman intellectual. Who was she? Where did she grow up? What are some of the key developments in her early life that shaped her ideas and political activism?

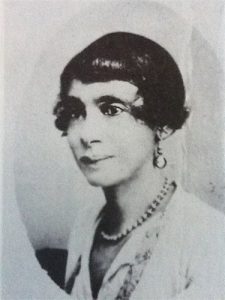

Courtney Morris: Madame Maymie Turpeau de Mena was an organizer with the UNIA who worked her way up from serving as a translator for various tours of the Black Star Line to become head of the North American Field and Marcus Garvey’s representative in the United States in the 1930s. She was born Leonie Turpeau in St. Martinville, Louisiana in 1879 and grew up in a working-class family of mixed-race gens de couleur. While there is limited documentation from this period of her life, it seems that the rise of Jim Crow in the post-Reconstruction era led de Mena and her siblings to leave the South in search of greater freedoms. While her brothers and sisters looked to the U.S. Northeast and the Midwest, de Mena set her sights south and moved to Bluefields, Nicaragua.

I posit that her life in Bluefields set the stage for her to reinvent herself as a cosmopolitan political subject. By the time she left Bluefields she had begun to publicly identify herself as “Madame de Mena.” It was there that she developed the performance of black respectability and empowered political subjectivity that she later modeled for the UNIA rank-and-file. The coverage in the Negro press reveals how effectively this performance worked – she had an extraordinary ability to pull people together, galvanize support among the rank-and-file, and revitalize moribund divisions that had been pulled apart through infighting. She was a master organizer and played a critical role keeping the UNIA together during a period of intense conflict and instability.

Fletcher: Your essay examines the political activities of Madame Maymie de Mena, a key leader in the UNIA. You argue that despite her political prominence and influence, she has been “undertheorized.” Can you tell us more about her marginalization in the primary and secondary sources and your thoughts as to why this has been the case?

Morris: I learned about Madame de Mena more than ten years ago as an undergraduate in a class that Frank Guridy, author of Forging Diaspora: Afro-Cubans and African Americans in a World of Empire and Jim Crow (2010), was teaching at the University of Texas at Austin. At that time, everything I read claimed that she was a Nicaraguan immigrant who came to the United States in the early 1920s. As I studied her life I began to realize that her standard biography had not been closely examined. This surprised me because by the late 1920s, de Mena was one of the most visible and important figures in the UNIA as demonstrated by the coverage in the Negro press and the UNIA’s publication, The Negro World.

So part of what I wanted to do in this piece is to trace the early part of her life, which had been largely ignored in the secondary literature and to find archival sources that would provide a richer account of her many migrations and political transformations. The fact that she has received so little scholarly attention is a reflection of the fact that perhaps she did too good a job renarrating her own biography—making it difficult for historians to produce accurate accounts of her life. But beyond that, the scholarship has tended to privilege what Lara Putnam refers to as “great man” accounts of Pan-Africanism that obscure the central role that women played in building this political project. There are, however, several scholars who are doing some important work on her including Natanya Duncan and Melissa Castillo-Garsow, which is an encouraging development.

Fletcher: Could you tell us more about how your work contributes to the growing literature on women, gender, and Garveyism—and Pan-Africanism more broadly? What do you see as the key historiographical interventions of the piece? How does the piece engage the scholarship of Ula Taylor, Asia Leeds, Keisha N. Blain and others?

Morris: Part of what I am trying to do in my work is to demonstrate how central black women are and historically have been to the making of diasporic networks of political solidarity, cultural exchange, and transnational mobilization in ways that are largely overlooked. I argue that these women were not passive spectators or obscure supporting actors but were at the frontlines building the political infrastructure to resist global white supremacy. My work on de Mena would not have been possible without the work of scholars like Ula Taylor, Asia Leeds, and Keisha Blain. They are all doing important work creating a space for black feminist historiography that enriches the broader field of black diaspora scholarship. I first read Ula Taylor’s biography of Amy Jacques Garvey when I began studying de Mena’s life. As a Central Americanist, I was thrilled to learn about Asia Leeds’ work on Garveyism in Costa Rica and black women’s participation in that political project. Finally, Keisha Blain is a dear colleague whose generosity provided the last crucial bits of information that helped me crack open the mystery of Madame de Mena’s life. Beyond that, I think her critical work on understudied figures like Pearl Sherrod in Detroit and Mittie Maude Lena Gordon in Chicago has opened up some important paths for understanding how actively black women were engaged in the global movement to dismantle white supremacy.

Fletcher: In your essay, you demonstrate how Madame Maymie de Mena anchored her identity in Central America in order to do diasporic work during the twentieth century. Can you tell us more about why she felt a non-U.S. Black identity was important to do this work?

Morris: It is difficult to know exactly how de Mena felt because the only materials that we currently have where we hear her actual voice are in the speeches she gave at Liberty Hall, articles that she wrote in The Negro World and The World Echo, a publication she later began with Father Divine’s Mission and various bits from the U.S. Negro and Jamaican press. But it appears that de Mena developed a public performance of diasporic cosmopolitanism. She came to prominence at a moment in which black people were actively working to collectively refashion and rearticulate themselves as modern political subjects. Black people were migrating from the U.S. South, the Caribbean and Latin America to urban areas in the U.S. Northeast and Midwest to pursue their own dreams of upward social mobility and economic self-determination. I think de Mena attempted to model this cosmopolitan subjectivity to the men and women who looked to her for political leadership to show them that black people were fully capable of becoming the kinds of political subjects who could both stand up to white supremacy and forge their own destiny.

Fletcher: Could you tell us more about how de Mena’s story overlaps with your larger book project? How does her life and experiences relate to the other activists and intellectuals you discuss in your forthcoming book? And finally, do you envision developing a future book project on Madame Maymie de Mena—perhaps a biography?

Morris: I began doing this historical research on de Mena because I wanted to historically map Afro-Nicaraguan women’s activism on the Caribbean Coast. De Mena will make an appearance in my book on black women’s activism and the geography of race. I include her in a chapter about women’s political activism and subjectivity in the early 20th century. I analyze her life in relation to the biography of Anna Crowdell, a Creole businesswoman who played a key role in Creole struggles for regional autonomy and economic power in the early 20th century. De Mena was married to Francis Mena, a Creole planter and activist, who was also a member of the Union Club, an important social organization led by the Creole elite, which regularly met at Anna Crowdell’s home. I suspect that the style of political leadership that de Mena later adopted in the UNIA was something that she learned and adapted from Anna Crowdell’s regional activism.

That said, I would love to write a biography of de Mena and the Turpeau family. They are a fascinating example of a family that committed themselves to being race men and women and fighting the violence of Jim Crow. In my travels, I have come across their names in all sorts of unexpected places – in Negro newspapers in the Midwest, in the archives of the Methodist Church, doing work with the YWCA in Chicago. I was fortunate to meet de Mena’s daughter, Berniza Kelley in Cleveland in 2014 before she passed away earlier this summer. She was deeply respected by her community although it appears that most people have no idea how involved she was with the UNIA or know anything about her famous mother. In order to understand de Mena better I think we have to understand her extraordinary family.

Kami Fletcher is an Assistant Professor of African American History at Delaware State University. She received a Ph.D. in History from Morgan State University in 2013. Her research centers on African American burial grounds, Black towns, and early 20th century Black female undertakers. Follow her on Twitter @kamifletcher36.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.