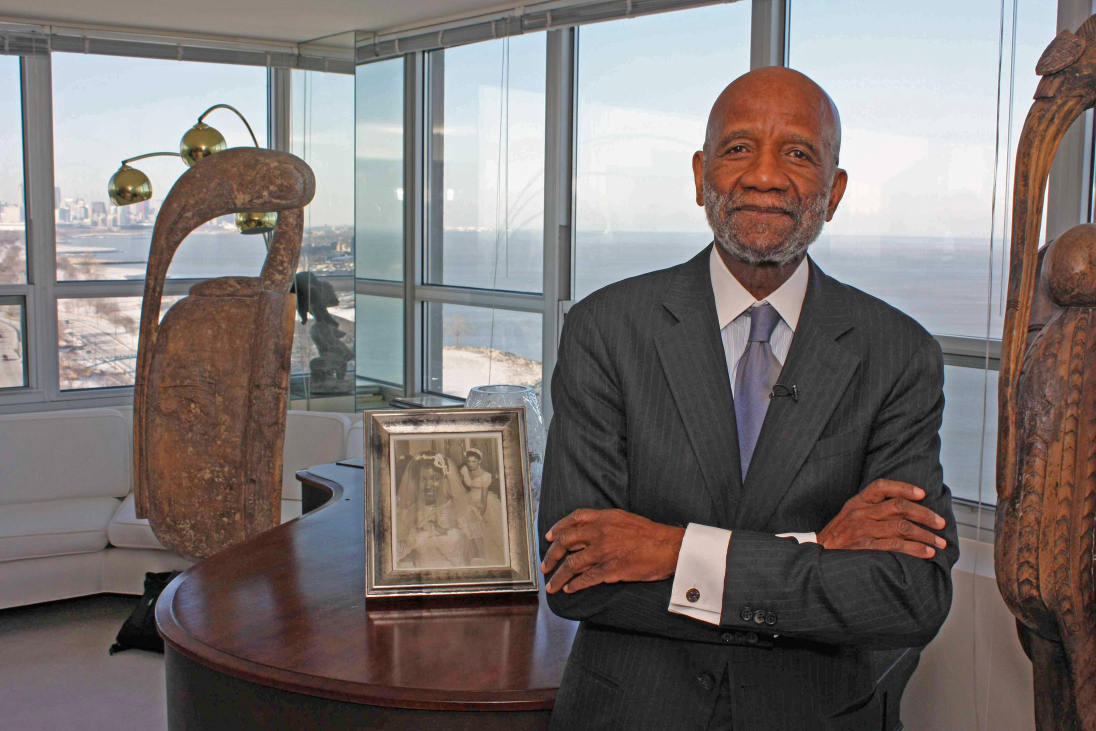

“History is Knowledge, Identity, and Power”: Lerone Bennett Jr., 1928–2018

When I found out about Lerone Bennett, Jr’s passing, I was immediately struck by his sense of poetic timing. In life, Bennett had been an eloquent defender of Black history and a strident advocate for Black rights. His ability to turn a phrase was as obvious on the page as it was on the stage. As the senior editor and in-house historian of EBONY magazine, Bennett’s incisive commentary helped to popularize Black history among millions of dedicated readers. As an author, educator and activist-intellectual, Bennett was willing to stand on the front lines of the movement as well as the front pages of the Black press. It seems fitting then, that his death would fall on the day we celebrated the 200th birthday of Frederick Douglass, another esteemed activist, journalist and educator.

A student of history as well as a teacher, Bennett had long been a fan of Douglass. He recognized the extent of his bravery, acknowledged the depth of his commitment, and appreciated his efforts to “uplift the race.” More importantly, Bennett understood Douglass’ role in helping to lay the foundations of the modern Black freedom struggle, as well as his ongoing role in its advancement. In a seminal 1963 article for EBONY, Bennett declared Douglass to be “as current as yesterday’s headline,” drawing a direct line between Douglass’ activism in the nineteenth century and the post-war Black freedom struggle.1

One hundred and ten years ago, he was staging sit-ins on Massachusetts Railroads. One hundred and six years ago, he was leading a fight for integrated schools in Rochester, New York. One hundred years ago he was denouncing hypocrisy and fraud with pre-Baldwin fury.

Many scholars have written eloquently on Bennett’s life and work, including this insightful piece by Christopher Tinson, which was published on this blog last year. I do not wish to simply repeat such work, which ably summarizes the trajectory of Bennett’s career and his enduring influence both inside and outside the boundaries of Johnson Publishing Company. Instead, I would like to use this brief reflection to consider what Bennett’s work and legacy might mean for historians and activists in the present.

As Tinson rightly acknowledges, Bennett’s understanding of Black history was both organic and pragmatic: history was something which “looks backwards and forwards simultaneously.” Drawing on cyclical conceptions of history espoused by European philosophers such as Nikolay Danilevsky, and connecting them to Afrocentric and Black activist traditions, Bennett emphasized the realness of Black history and its relevance to the Black experience in the present. Pero Dagbovie is one of a number of scholars to note this trend in Bennett’s writing, arguing in his 2010 work African American History Reconsidered that Bennett sought to articulate a vision of Black history that was “functional, pragmatic and this-worldly in orientation.” By the 1980s, against the backdrop of Reaganism, racism and Black political realignment, Bennett’s understanding of the form and function of Black history had solidified. 2

History is knowledge, identity and power. History is knowledge because it is a practical perspective and a practical orientation. It orders and organizes our world and valorizes our projects.”

What might Bennett make of our current historical moment? I’m confident that surprise would not be among his reactions. In his writing, Bennett had a knack for isolating and interrogating the historical precedents to current events: the radicalism of Black Reconstruction, which informed the rise of Black Power, or the white backlash of the 1970s which echoed the efforts of southern Democrats to “redeem” the South a century earlier.3 In an October 1989 article, Bennett outlined the defection of white liberals, the growing economic power of industrial capitalists, unease over welfare, taxation and immigration, and a new and conservative Supreme Court, dryly noting that such developments were “scenes from a movie we’ve seen before.”4

In an age when almost every action by the president is treated as “unprecedented,” Black historians more than most understand that the activities of this administration are rooted in historical processes and racialised hierarchies of power and privilege. To paint this administration as “un-American” is to misunderstand the roots and routes of the African American experience which have brought us to this moment, with this president. Unprecedented? One might argue the Trump administration is “as American as Cherry Pie.”

Donald Trump celebrates the “greatness” of American history because he does not understand American history, and even less so the place of Black history within it. As Bennett argued, Black history constitutes a “total critique” of American history. It helps to turn American history inside out, “revealing it to be the precise opposite of what it claims to be.” Throughout his life, Bennett reminded his readers that “it is difficult, if not impossible, to understand American history without some understanding of the Black experience.” In turn, his work serves to place the current administration within a longstanding pattern of progress and backlash, but also points to how history can help us to resist such forces.

In his 1982 article, “Why Black History Is Important To You,” Bennett contended that we do not “receive” the past as a passive, inert form of knowledge: “We make it by resuming the past in a contemporary project based on a projection into the future.”5 Expressed in a different way, Bennett’s work outlined our ability to give form and function to the past by acting on it in the present. From this perspective, we can see how the actions and ambitions of Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth live on in the lives of Ella Baker, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, and in turn, how their lives inform our ongoing struggles for civil rights. Similarly, organizations such as the African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS), and leading activist-intellectuals in the present owe a debt to the work of Bennett and other pioneering Black historians who struggled to make Black history “equally concrete and equally alive.”

- Bennett, “Frederick Douglass: Father of the Protest Movement”, Ebony, September 1963, 50. ↩

- Bennett, “Why Black History Is Important To You”, Ebony, February 1982, 61. ↩

- E. James West, “Black Power Is 100 Years Old”, The Sixties (2016); E. James West, “Lerone Bennett Jr., A Life in Popular Black History”, The Black Scholar (2017). ↩

- Bennett, “The Second Time Around”, Ebony, October 1989, 46. ↩

- Bennett, “Why Black History Is Important To You”, Ebony, February 1982. ↩