A Troubled Past: The United States and Africa since World War II

A few weeks ago, President Donald Trump sparked yet another international controversy with his reference to “sh**hole countries” to describe immigrants from Haiti, El Salvador, and African nations. While the media has since moved on to other stories, including the president’s widely anticipated first State of the Union address, Africans are not quite ready to forgive and forget.

At the recent African Union Summit in Addis Ababa, various African leaders demanded an apology from the president. African Union Chairman Moussa Faki Mahamat listed Trump’s remarks among a host of others “on Jerusalem and the reduction of contributions to the budget for global peacekeeping,” as reason for Africans’ anger. “The continent will not be silent on this subject.”

Far from an aberration, Trump’s behavior is indicative of a decades’ long history of American racism towards Africa and its descendants. Repairing that relationship requires more than an apology from the 45th president; it demands reckoning with that history.

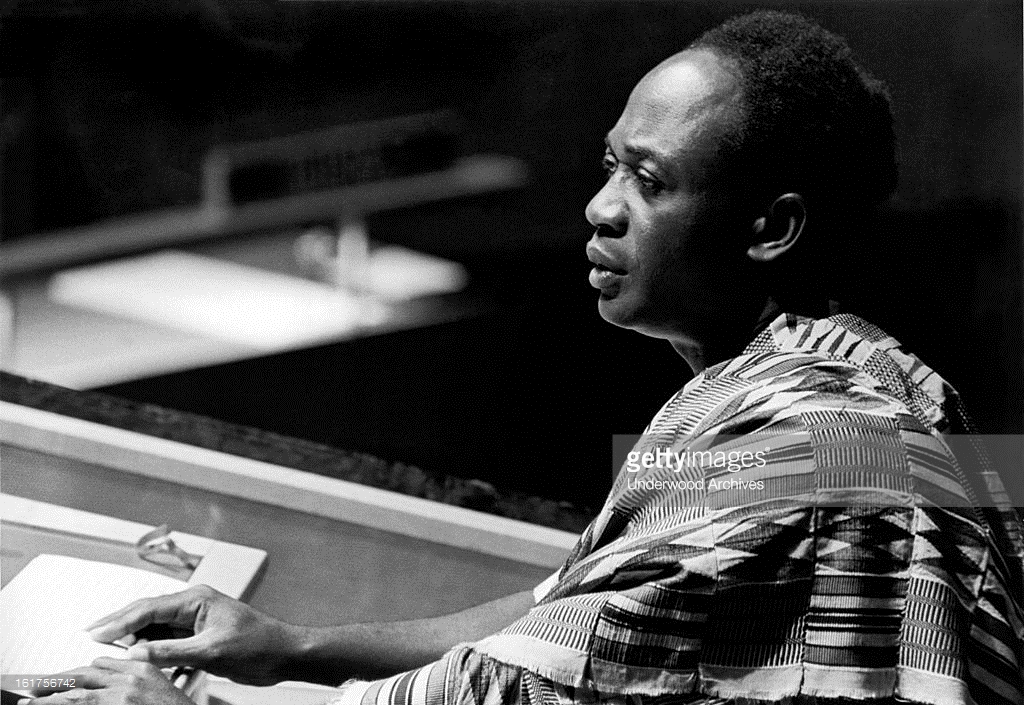

Africa emerged from World War II eager to throw off the chains of nearly a century of European colonial rule. Building on the momentum generated by previous decades’ anti-imperial movements and taking advantage of British fatigue on the “colonial question,” Ghana became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to declare its independence in March 1957. Shortly thereafter, seventeen other countries—including Nigeria, Senegal, and Congo—gained their independence in 1960, which has been termed “The Year of Africa.”

Attentive to these changes, President Dwight Eisenhower announced the creation of the Bureau of African Affairs in recognition of the continent’s new significance.1 He also sent Vice President Richard Nixon on a three-week tour of the continent, which included stops in Tunisia, Morocco, Liberia, Libya, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Ghana.2

Despite the “goodwill” mission of the tour, Nixon’s visit revealed the administration’s ignorance when it came to dealing with non-Europeans. At a state dinner during the celebrations honoring Kwame Nkrumah’s inauguration as the first president of Ghana, Nixon leaned over to a man sitting next to him and asked, “How does it feel to be free?” To Nixon’s surprise and embarrassment, the man replied, “I wouldn’t know, I’m from Alabama.”

Nixon’s gaffe mistaking a man from Alabama for a Ghanaian shed light on the issue of American racism in dealing with Africa. “It is not Russia that threatens the United States so much as Mississippi,” claimed the great African American intellectual W.E.B. DuBois in his preface to “An Appeal to the World: A Statement on the Denial of Human Rights to Minorities in the Case of Citizens of Negro Descent in the United States of America and an Appeal to the United Nations for Redress.” Locked in an escalating battle with the Soviet Union for global influence, US officials increasingly struggled in the post-war era to address criticism of the country’s treatment of people of color. In a 1963 memo to his superior US Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Thomas Hughes complained of Soviet propaganda claiming that racism was endemic to American capitalism and that any gesture of goodwill on the part of the US toward Africa was merely a cover for “American monopolies . . . to get hold of . . . African riches.”3

Hughes’s memo was merely one of many written by State Department officials concerned about the effects of American racism on US-Africa relations. Indeed, as the civil rights struggle in the US heated up, US officials encountered increasing anti-American sentiment from Africans. In May of 1961, the world watched in horror as white mobs beat and firebombed civil rights activists participating in the Freedom Rides, which aimed at drawing attention to segregation on interstate buses. News of the violence carried out against the Freedom Riders spread quickly with African newspapers condemning the lack of government protection for those fighting for their rights as citizens. “Surely the Negro problem on the earth as well as the plight of oppressed peoples in Africa and elsewhere demand much more serious attention and consideration than the sending of a man to the moon,” stated the Ghanaian Times.4.

In an effort to minimize the damage caused by the attacks on civil rights activists in Alabama and elsewhere, US officials employed African American ambassadors to sing—sometimes literally—the praises of American democracy and free enterprise. Launched in 1956 the Jazz Ambassadors program sent prominent musicians—including Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong, and Duke Ellington—on tours throughout the world, where they often played to sold-out venues and adoring fans. Over the years the list of ambassadors expanded to include other prominent African American lawyers, politicians, and businesspeople, including Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, Congressman Andrew Young, and General Motors director Leon Sullivan, all of whom played a crucial role smoothing over relations with Africans.

Even with Armstrong and others traveling the world on behalf of the US government and business, Americans continued to draw criticism for their racist behavior vis-à-vis Africans and their descendants. In 1972 the Organization for African Unity (OAU), the predecessor to the African Union (AU), released one of several resolutions “strongly condemn[ing]” the US and other governments for their continued support of South African apartheid, a system “designed to consolidate and perpetuate domination by a white minority and the dispossession and exploitation of the African and other non-white people.” The OAU further declared that “those States which supply arms to South Africa,” including the US, were acting in opposition to African aspirations “for freedom, equality and justice.”

Subsequent decades have continued to witness strains between the US and Africa. After his widely celebrated election as the first African American president, and one with familial ties to Kenya, Barack Obama disappointed many Africans when he failed to live up to expectations regarding US investment in the continent.

Given the past half-century of US-Africa relations, in which Africa has often been viewed begrudgingly, relevant only in relation to US broader struggles with the Soviet Union and China, Trump’s remarks should come as no surprise. Especially coming from an avowed racist. If anything they should remind us of the debt Americans owe to Africans and their descendants for years of mistreatment: a debt that cannot be repaid with a mere apology, if at all.

- Aide for Africa Names: Satterthwaite is Appointed to New State Department Post,” New York Times, August 21, 1958: 2. ↩

- Russell Baker, “Nixon Leaves Today for Tour of Africa” New York Times, February 28, 1957: 1. ↩

- Memo Thomas L. Hughes to Secretary of State, Subj. Soviet Media Coverage of Current US Racial Crisis, June 14, 1963, Papers of John F. Kennedy, Presidential Papers, National Security Files, Civil Rights: General, June 1963: 11-14. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. ↩

- Mary Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 159-161 ↩

The author must be commended for this was well written piece of untold and unknown history. I would subscribe that the vast majority of Americans, including politicians, and most certainly many political leaders are unaware of the disdain of Africans towards the U.S for its silence towards colonization of, and indifference towards Africa. Additionally, the deprivation of basic human rights and continued treatment of people of color in the United States, and even minority (tribal) groups in Africa is building resentment by the poor, underclass and exploited in Africa and underdeveloped countries. This in turns builds on the notion that Africa is a continent only to be thought of in regards to its mineral wealth to benefit the wealthy.