The History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital

2018 marks the fiftieth anniversary of a crucial moment for Washington, D.C. On April 4, 1968, following news of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, Black Washingtonians burned U Street corridor businesses to the ground. Forty years later in this same spot, the U Street community embraced a moment of optimism as they celebrated the election of President Barack Obama.

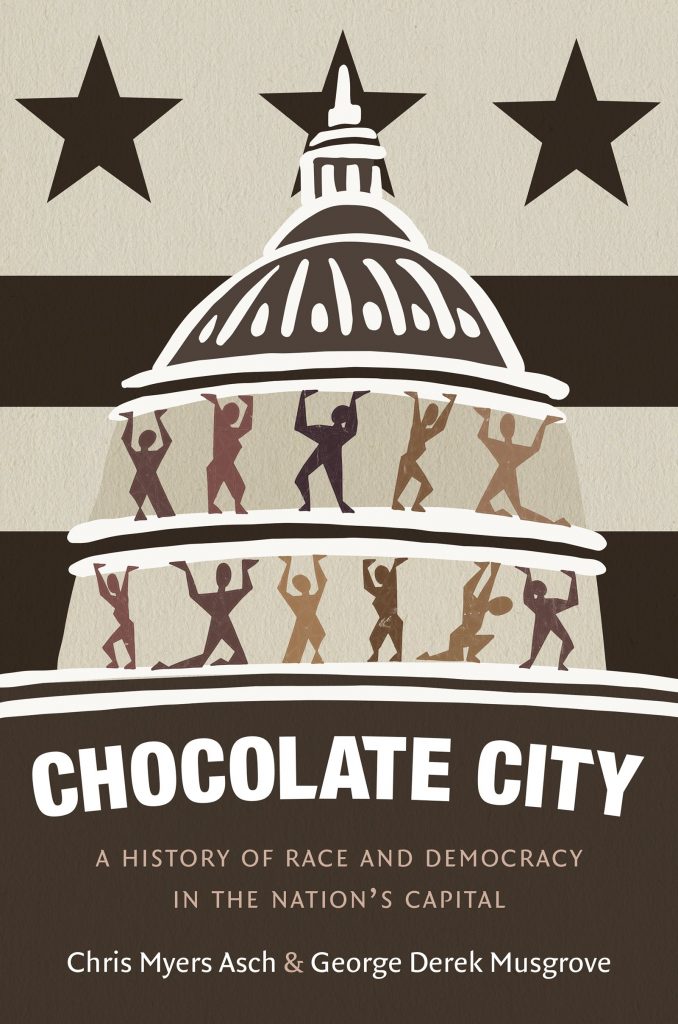

Historians Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove’s well-written 500-page book, Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital, tells a sociopolitical story of race in Washington, D.C. from colonial America through the present. The book restores the centrality of Black American perspectives and experiences into Washington, D.C.’s local history. Asch and Musgrove trace triumphs and tragedies that have played out on this national stage. Chocolate City reveals not only that the D.C. community has been emblematic of widespread struggles for racial equality, but also that the story of this nation’s capital is fundamentally about Black Americans’ struggle as they resisted white supremacy in America.

Like most of the United States, the land on the Potomac River was once home to Native American peoples. By 1790, however, Anglo American colonial settlers had ensured that the Nacostine people were “long gone” and that their society was a “distant memory” (15). Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison convened at Jefferson’s lodging that summer to coordinate the passage of Hamilton’s financial system and the coronation of Washington, D.C. as America’s capital. From enslavement through the civil rights era, the Washington community lived out the spirit of the Compromise of 1790, meaning that elite policymakers exploited almost every chance to discriminate against Black Washingtonians.

Unlike older scholarship, this book makes clear the reality of enslaving men and women in private homes and public places for the first half-century of the republic. Asch and Musgrove include the image of Ann Williams leaping from a third-story window to escape her enslaver’s plan to sell her and send her to the South. Printed in abolitionist Jesse Torrey’s 1817 antislavery tract, this portraiture helped convince policymakers down the road on Capitol Hill to stop trading humans in the nation’s capital.

During the Civil War, Black Washingtonians were among the first to take up arms in pursuit of their freedom. Asch and Musgrove explain: “The sight of [African American] men in crisp blue Union uniforms drilling confidently on Washington’s streets captured the vast changes in [African American] status engendered by the war” (132). On April 16, 1866, the first D.C. Emancipation Day parade overflowed the streets. In 1867, Major General Oliver Otis Howard, commissioner of the new Freedmen’s Bureau, founded Howard University, which has since thrived as a historically African American college in Northwest Washington, D.C. Still, Asch and Musgrove carefully emphasize that whereas Black Americans “saw emancipation as just the first step toward becoming full citizens, most white Washingtonians viewed emancipation as the final destination, a ceiling for black aspiration” (132). In the federal government, white women actively pushed African Americans out of jobs at institutions such as the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, which increasingly turned to women and African Americans during the Reconstruction era.

Asch and Musgrove’s selection of key figures and events reveals that the twentieth century was a mix of gains and losses for Black Washingtonians. In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson formally segregated the federal workforce. In the 1920s, the U Street corridor’s version of the Harlem Renaissance embodied cultural resistance and triumph in the face of increasing structural racism. In the 1930s, the Great Depression steamrolled Washington, D.C., devastating Black American communities as the New Deal mostly helped white people.

The last one hundred pages of the book draw from magazines and newspapers in local D.C. archives to explore contemporary gentrification, drugs, immigration, transportation, and the 1968 riots. The D.C. civil rights movement culminated in the riots, which spread past the U Street corridor onto H Street Northeast and Southwest Washington, D.C. They write: “Many black Washingtonians saw the riots as cathartic and were hopeful for a post-riot renaissance” (357). Throughout the rebuilding phase, however, as young white urban professionals moved into African American neighborhoods, they pushed longtime Washingtonians into Maryland and Virginia. The new residents owed their spacious, walk-able downtown to decades of African American activism and resistance, particularly against a highway system that would have transformed the layout.

Although the book’s subtitle–“A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital”–suggests that it would examine various racial groups, it underemphasizes the history of Latinx Washingtonians rallying around a pan-Latinx identity to advocate for themselves. Asch and Musgrove highlight the prominent Latinx Washingtonian, Carlos Rosario. They note that Rosario died, but they do not mention that the Latinx community paraded through Latinx neighborhoods behind his casket. The introduction indicates that the book explains why “racial mistrust” is “deeply ingrained in the nation’s capital,” so more Latinx history would have strengthened the text–even if this proves beyond the scope of Chocolate City.

Any omissions or shortfalls are likely consequences of the ambitious scope of this book. Using wide-ranging sources to illuminate nearly four hundred years of content for popular and scholarly audiences, Asch and Musgrove’s achievement is quite the feat. They draw upon journals, letters, memoirs, legal records, speeches, and especially newspaper archives at the D.C. Public Library. Local newspapers chronicle the history of the first majority African American city. Asch and Musgrove’s legal analysis of home ownership – reappearing throughout the book – epitomizes the structural racism that longtime residents have faced. Journals, memoirs, and speeches enable Asch and Musgrove to open most sections by introducing a person who exemplified key themes. Informative headings such as “Go home rich white people” mark each section (425).

Reflecting the expertise of each author, Chocolate City fuses African American historiography with D.C. scholarship because D.C history is fundamentally the story of Black Washingtonians. Significantly, Asch and Musgrove’s analysis of race combats the myth that Washington, D.C. is no more than an entitled political swamp, which bestsellers by political journalists – such as Eliot Nelson’s Beltway Bible and Mark Leibovich’s This Town – perpetuate. Asch and Musgrove emphasize Black Washingtonian perspectives within D.C. history, and they advance Washington, D.C. within African American scholarship, joining other recent works including Treva Lindsey’s Colored No More.

Chocolate City is neither a story of passive victims nor triumphant victors. The authors strike a delicate balance between a struggle narrative and real resistance and empowerment. Their synthesis recounts a familiar tale for the people of color who lived it. White residents in D.C.–especially young urban professionals–should especially take it upon themselves to learn this important history.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.