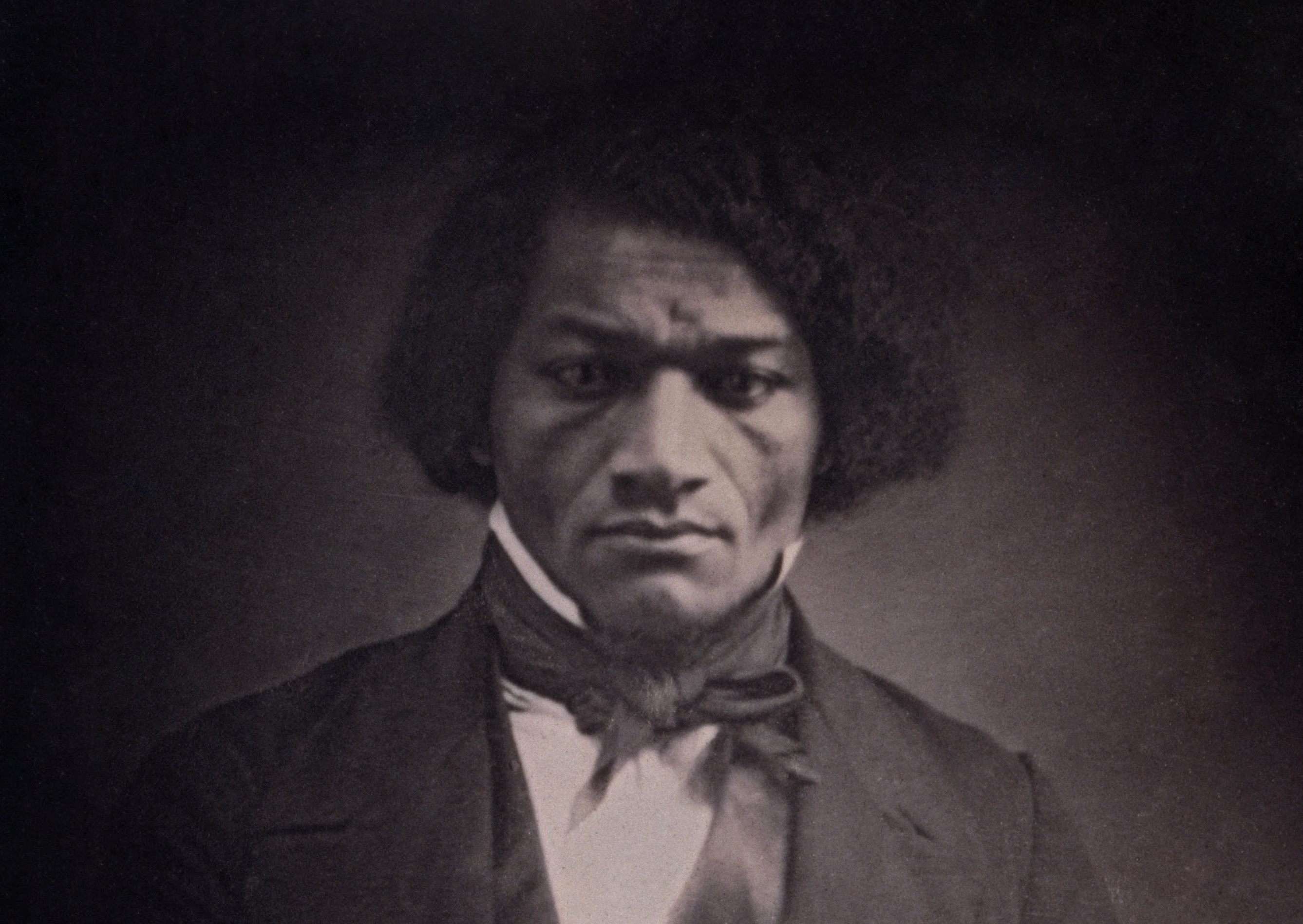

Frederick Douglass’s Life and Labors

“SLAVE-children are children,” Frederick Douglass wrote in his 1855 autobiography My Bondage and My Freedom. David Blight’s new study of Douglass proceeds from that point, exploring young Frederick’s life in Maryland in the early nineteenth century, illuminating the human experience of a person who was bought and sold as property. Blight uses Douglass’s writings to examine the emotional and psychological experiences of slavery, the ways enslaved people were made to understand the terms of their bondage, and how those experiences shaped Douglass’s antislavery politics. Douglass’s childhood offers a compelling framework for the book. Raised in slavery, he then escaped and related his story of bondage to expose and denounce the system that rendered him property. Blight is interested in the man who was once enslaved as much as he is in the political work Douglass built upon his experiences. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom unveils the complex humanity of a public figure who, to a great extent, worked to maintain his privacy. Through vivid prose and meticulous detail Blight explores the intellectual influences of Douglass’s politics, the emotional journeys of his personal and working relationships, and the persistent desire to be heard that determined so much of Douglass’s life. The book is at once an analysis of Douglass’s wide-ranging political labor and a sensitive portrait of his personal life.

For all the peculiar opportunities he enjoyed—life in a city, hiring his time, the chance to learn to read—Douglass’s early life comprised many of the most common experiences of slavery in the antebellum South. He came to understand the instability, violence, and injustice that defined the institution. His family members were brutally beaten and his fellow enslaved people were killed with impunity. Amidst these horrors, Douglass built intense and formative connections with others, including a close relationship with his grandmother and friendships with various cousins. Perhaps most importantly, when he was a teenager, Douglass led a clandestine “Sunday school” on his plantation, which deepened his Protestant faith, and helped him cultivate his oratorical skills. As was the case for so many others, Douglass’s enslavement involved tremendous suffering, occasional physical opposition to his owner’s authority, and critical emotional connections with fellow bondspeople. In the book’s early chapters, Blight reconstructs various ideas that shaped Douglass’s later politics, including Douglass’s awareness of the exploitation of slavery, the injustice of forced Black colonization, and the power of religious faith.

At times, the structure of the book’s earliest chapters is disorienting. The focus shifts frequently between Blight’s history of enslaved childhood and his analysis of the antislavery project Douglass undertook in his writing. Blight notes that any biographer of Douglass faces this challenge in the sources—Douglass was, after all, his own first biographer, and his writing necessarily shapes accounts of his life. Still, Douglass’s writing is central to this story because words were critical to his political significance. And the act of writing was therapeutic, empowering, and liberating for a man once enslaved. We know so much about Douglass because he wrote so extensively, and through his writing he helped remake the United States as he remade his own life.

As he rose to prominence, Douglass’s fame was a source of both political opportunity and personal conflict. Due to his skills as a writer and public speaker, white abolitionists saw him as a crucial tool for their fight against slavery. To some, Douglass was the best evidence of slavery’s injustice because no person so brilliant should be held as property. White abolitionists paraded Douglass “as [a] symbol, as an exhibit of the black man, the slave with a stunningly informed, active, and brilliant mind” (104). Douglass relished opportunities to use his skills in the antislavery struggle, but at the same time, Blight illuminates the ways Douglass struggled against white allies seeking to control him and to flatten his humanity.

Douglass worked through these constraints, hoping to capitalize on his fame and use his profile to promote his political ideals. He fled slavery in 1838 and only seven years later became perhaps the world’s best known Black man when he published his Narrative. Douglass then spent nearly two years traveling the United Kingdom in the late 1840s. He cultivated his reputation among an Atlantic circle of abolitionists. In the U.K., Douglass forged relationships that enabled him to launch his own newspaper, The North Star, and act independent from the controls of his colleague William Lloyd Garrison, a leading white abolitionist who demanded that fellow activists follow his narrow ideological path. Though Douglass was increasingly celebrated during his lecture tour, he chafed under the controls imposed by white “handlers” who were ostensibly acting as his hosts. Throughout the nineteenth century, Douglass’s celebrity enabled him to publish a series of periodicals with the backing of white financiers. He also met with, and perhaps influenced, President Lincoln’s emancipation policies, and after the Civil War he was positioned to hold various appointed offices, including U.S. Marshal of Washington, D.C., and Minister to Haiti.

But Douglass’s public profile also made him a target for virulent personal and ideological attacks. Garrison’s followers denounced him for his political independence and later, both white and Black Americans bitterly criticized his second marriage to Helen Pitts, a white woman twenty years his junior. Douglass lived as a symbol, carrying complex meanings for various factions during his life. This made him both powerful and vulnerable, producing tremendous opportunities and significant anguish. Blight has crafted a biography of an intellectual and activist that does not lose sight of the anger, anxiety, resentment, despair, and multiple forms of love that shaped so many of Douglass’s choices.

Fame made it possible for Douglass to support his family by traveling and lecturing, using language to fight slavery and pursue racial justice, but Blight interweaves compelling discussions of the toll that activism wrought upon Douglass’s household. Throughout, Blight emphasizes Douglass’s interconnected personal and political worlds. In his early years on the antislavery lecture circuit, relentless travel and writing strained Douglass’s physical and mental health. And during these tours, his first wife, Anna, was often left alone with the responsibilities of caring for their five children. This stress was especially pronounced during the Civil War; Douglass crisscrossed the North recruiting Black men for the fight while at the same he and Anna worried over their sons, who had chosen to serve in the conflict. Blight notes that Anna Douglass surely experienced a particular kind of angst, with so much of her family scattered in support of the war effort. And in his later life, Douglass’s work produced tensions over money, as he remained the chief provider for his children and their families.

Blight is sensitive to Anna’s emotional state throughout and highlights how critical her support was for sustaining Douglass’s activist career. Blight raises important questions about how Anna would have felt during Frederick’s extended absences, and he meditates on how she likely experienced Douglass’s professional, personal, and possibly sexual relationships with the activist women Julia Griffiths and Ottilie Assing. As Blight acknowledges, Anna is a difficult subject for the historian because she never learned to write. But there are moments when he might have taken a more critical approach in an effort to do her justice as a historical actor. Blight suggests that when Frederick departed for the United Kingdom in the 1840s, Anna, left to raise their three young children, might have understood that “it simply was hers to do and not to ask why” (140). And Blight notes that when Douglass completed Life and Times, his third autobiography, he mentioned Anna only once, and not by name, in its more than 600 pages. Anna, Blight says, “remained forever a subject about whom [Frederick] could not write public words” (634). Anna Douglass is marginal in so much of the historical record in part because Frederick Douglass actively marginalized her in so much of his life and writing. Theirs was a marriage defined by conflicts and tensions that likely cannot be known. While Blight has produced a deeply personal biography, he might have done more to illuminate the range of emotions Anna Douglass surely felt and expressed. Further, he might have considered the ways Anna struggled against her husband’s interests and examined Frederick’s conscious choices to push his wife to the edges of his public life.

In short, this is a remarkable biography of Frederick Douglass as a person and a political actor, centering him in some of the most critical transformations in United States politics, law, and society. Blight illuminates the broad range of Douglass’s activist pursuits, the wide array of places and times he navigated during his long life, and the various beliefs that motivated him to pursue particular political strategies. The book is an essential and exhaustive account of Douglass’s incredible life and labors.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.