The Trauma of Racial Violence in Frederick Douglass’s America

*This post is part of the online forum on The Futures of Frederick Douglass. The contributions in this forum each highlight innovative approaches to the study of Douglass’s life and works.

After the police officer shot her mother’s fiancé seven times at close range, the little girl jumped out of the back seat of the car and ran for her life. Another police officer caught her in flight and put her into his patrol car. Her mother, who also witnessed the event, was handcuffed and also put into the same car. At some point the four-year-old, with great anxiety in her voice and tears streaming down her face, told her, “Mom please stop the cussin’ and screaming because I don’t want you to get shooted!” Her mother turned to her daughter and said, “Okay. Give me a kiss.” Reaching out with both her little arms, she tried to console her mother. “I can keep you safe,” she said. “That’s okay,” the mother responded, “I got it.” The daughter nodded okay, and then perhaps out of relief, began to sob softly. Her mother instructed her to lean closer and said in barely a whisper, “I can’t believe they just did that.” The daughter reached in to hug her mom again, only this time letting out deep, heart-wrenching sobs. The mother put her head down on the little girl’s shoulder in an attempt to console her. But out of frustration that she could not embrace her weeping child because her arms were handcuffed behind her back, she yelled out, “Damn, there’s no way I can take these b****es off?” The daughter immediately jumped back and screamed, “No! Please, no, I don’t want you to get shooted!” The mother rocked as if in pain. “They’re not going to shoot me, okay? I’m already in handcuffs.” The child, still sobbing, told her mother, “Don’t take them off. Do not take them off!” She looked out the window at the police, and then leaned back in the seat and cried, “I wish this town was safer!” And now wailing uncontrollably she pleaded, “I don’t want it to be like this anymore!” With the utmost gentleness the mother suggested, “tell that to the police, okay?”

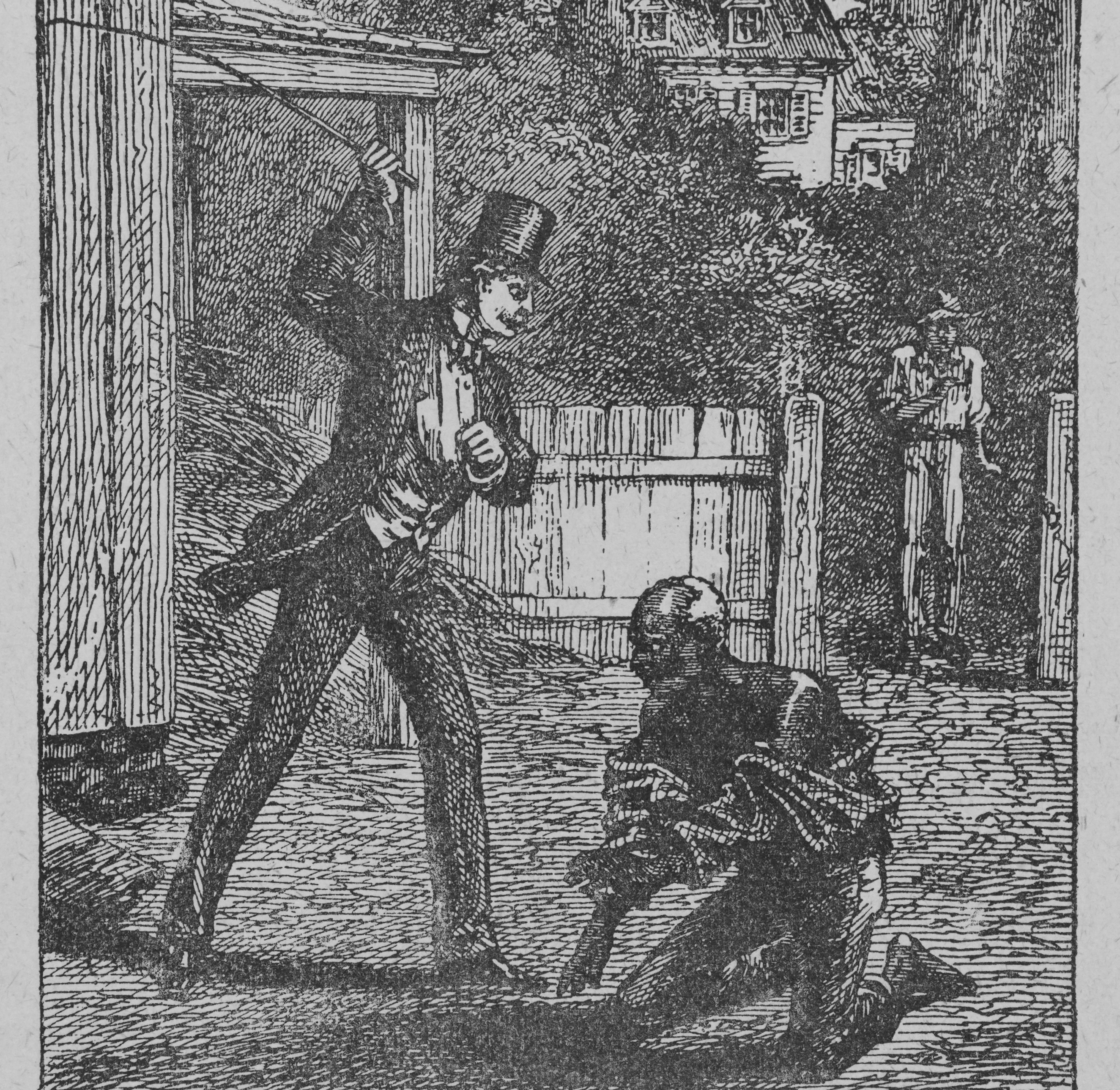

The story is familiar. Thirty-two year-old Philando Castile was killed on July 6, 2016 after being stopped for a minor broken taillight traffic infraction. The violence that this young girl and her mother, Diamond Reynolds, witnessed and the trauma that they endured are also familiar. Indeed, trauma due to the phenomenon of extralegal and irrational violence has plagued the Black community for centuries. It shaped the institution of slavery and the post-emancipation South. But it is deeper and much more nefarious than that. For the violence that Black people in America experienced (and continue to experience) was always tied to white ideas that Black people deserved to be exterminated—vanquished through a war between the races.

Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass understood and grappled with the continuity of these ideas, racial violence, and the trauma that it fostered throughout his lifetime. Douglass was especially concerned about those who advocated for “a war of races between the negro and the white man in which the negro would be annihilated.”1 The issues that would generate this catastrophe were always centered around Black freedom and civil rights. And in 1863, as I discuss in my book, A Curse upon the Nation: Race, Freedom, and Extermination in America and the Atlantic World, Douglass was emphatic about what many Black people continued to fear and what Americans talked incessantly about during the Civil War, which was that “the white people of the country may trump up some cause of war against the colored people, and wage that terrible war of races which some men even now venture to predict, if not desire, and exterminate the Black race entirely. They would spare neither age nor sex.”2 But Douglass denounced what many newspapers would call the solution to the Negro problem by saying:

But is there not some chosen curse, some secret thunder in the stores of heaven red with uncommon wrath to blast the men who harbor this bloody solution? . . . Such a war would indeed remove the colored race from the country. It would fill the land with violence and crime, and make the very name of America a stench in the nostrils of mankind. It would give you hell for a country.3

The exterminatory violence that Douglass warned about and knew well was not mere hyperbole. The Black community was constantly threatened with extermination if they, for example, attempted to rebel against their enslavement, or asserted their civic rights to compete and prosper economically. This was true in the South and the North, as Douglass noted that even in “Brooklyn colored men had been driven from their work and mobbed for no other reason than the color of their skin.” And he warned that if you “kill them off” white Americans would be killing the “Justice” and “Humanity” within themselves.4

The way that this sort of violence plays out as it relates to historical trauma is that intuitively Diamond Reynolds’s little daughter knew that she was in danger. Neither her status as a child, nor her mother’s status as a female, exempted them from potential harm. The history of racial violence in America reveals that women and children were often the victims of deadly violence during enslavement and as freed people.

As a society, we often rightly focus on the victims of murder and violence, but fail to see the harm that it does to those who witness it. Scientists now understand the phenomena of cellular memory and generational memory, whereby all traumatic experiences are absorbed by the cells throughout the body and are passed down generationally. Science has caught up with the Black community’s lived experiences of historical trauma, and intuitively we know that money and time will not fix the harm that was done that day. And what Douglass chose not to discuss above is that this continuum of denying people of color civil rights and social justice made, and continues to make America “a hell” for African Americans. Because of their race, members of the African diasporic community were, and are, never sure if they too might not run into color prejudice that ultimately ends their life, or their child’s life, or their sister’s, brother’s, mother’s, father’s, uncle’s, aunt’s, cousin’s, and even grandmother’s or grandfather’s life without cause. The deep-seated trauma that this historical reality generates does have a cost, and it remains part of the Black experience in America.

Douglass understood 155 years ago that African Americans must receive full “political,” and most importantly, “social equality,” because anything else was intolerable. The Black community needed protection from the trauma of racial violence that they experienced every day. For Douglass that was “the only foundation upon which the peace of the country can ever be permanently secured.”5 Certainly he is referencing times during the Civil War, but Douglass might just as easily be referencing our own times of racial and ethnic strife and social disequilibrium. It is indisputable that racial violence continues in this country, and that there are those who advocate white supremacy and white nationalist ideology. But those Americans who encourage the country to be divided by the race of its citizens and those who dismiss the idea that historically Black lives have not mattered are also responsible for the cultural incompetence that exists in our institutions and the racial dissonance that exists today, and they too must be held accountable. Douglass, a diehard fighter for social justice, hoped that “bye and bye you [white America] will get over all this nonsense” of color prejudice—nonsense that manifests itself today in the institutional violence that Diamond Reynolds’s daughter witnessed, which continues to have deadly ramifications for Black and brown communities across the country.

The police officer who shot Philando Castile, Jeronimo Yanez, told his fellow officer that he “was getting f***ing nervous” right before he pulled the trigger. He later was found not guilty by a jury who could not agree if Yanez’s actions fell under the legal definition of culpable negligence; that he, with careless disregard for a Black man’s life, shot Mr. Castile seven times unlawfully.6 The history of racial violence in this country that Douglass was concerned about, the tearful plea of a traumatized four-year-old for it not to “be like this anymore,” dictates that we not second guess the jury in their decision, but rather that we seriously reexamine the history of racial violence in America and the trauma it has caused, and reconcile the history of slavery and the mythology of Black criminality with the othering of Black people on which this country was founded. For in that dark and deeply disturbing history is our salvation.

- “What Shall Be Done with the Negro. A ‘Colored’ Man’s View of It,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 16, 1863. ↩

- Quoted in Kay Wright Lewis, A Curse upon the Nation: Race, Freedom, and Extermination in America and the Atlantic World (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017), 178-79. ↩

- Quoted in ibid., 179. ↩

- “What Shall Be Done with the Negro.” ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Jon Collins, “74 Seconds: The Trial of Officer Jeronimo Yanez,” MPR News, June 16, 2017. ↩