The Sexual Criminalization of Black Women

This post is part of our online roundtable on Anne Gray Fischer’s The Streets Belong to Us

The Streets Belong to Us insists on the critical importance of women and women’s bodies as the mechanism by which state power, through discretionary law enforcement practices, operated. Anne Gray Fischer writes, “…It is not enough to say that women are also policed or differently policed. Women’s bodies are an important and overlooked site on which police power-and the modern city—has been built” (4). Women’s bodies, particularly the bodies of Black women, acted as the constitutive material that made up the very fabric of state power and racial segregation.

This innovative, deeply researched, and forcefully argued book deciphers an overlooked mechanism by which the state executed violence—namely sexual policing, or “the targeting and legal control of people’s bodies and their presumed sexual activities”(2). Making skillful use of a range of sources, Fischer advances research on the history of policing by focusing on Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Boston (cities with trajectories that reflected national trends). The Streets Belong to Us argues that sexual policing, among other forms of law enforcement practices, played a unique role in the process by which police power consolidated over the course of the twentieth century. While white women were targets of sexual policing, over time, sexual liberalization moved the target of morals enforcement far more pointedly in the direction of Black women’s nonmarital heterosexual practices. This meant that white women’s nonmarital heterosexual practices were decriminalized as Black women were increasingly criminalized. The book draws on Black feminist theory and methodology to not show simply show the differentiation in Black women’s and white women’s relation to state power, but to also point out that differentiation itself carries useful explanatory power to decode the ways that police power functioned.

If Fischer left the argument at the nature of police power and the fundamental role of women’s bodies to its construction, then The Streets Belong to Us would have done much to advance our knowledge. But this book is not only a history of incarceration, policing, and criminal justice in the United States, it is also urban history. On this front, the book offers deeply generative insights. Fischer convincingly shows that sexual policing was the bedrock of the making and remaking of the modern city; that it is impossible to understand the history of racial segregation without factoring in law enforcement’s presumptions about the sexual behavior of Black women. Sexual policing, Fischer argues, legitimated, legalized, and sanctioned the mass expansion of police power. Focusing the lens on “mass morals misdemeanor policing” makes clearer the core processes that defined US urban development in the twentieth century: the relocation of “urban vice” to Black neighborhoods; white and capital flight; the infamous urban renewal programs that led to the wide displacement of Black working-class people; and the urban planning projects designed to attract white patrons to downtown commercial development. Unfolding along women’s quotidian lives, sexual policing mapped and re-mapped patriarchal and racial power onto cities’ built environment and the boundaries, within and without, that defined them.

This stunning book offers a fresh history of police power by linking it to the development of the modern city from the Prohibition era into the 1980s. In so doing, Fischer provides a long view of policing instead of a narrative that begins, perhaps more typically, in the post-World War Two period. In the 1920s, during Prohibition, Fischer explains, many viewed law enforcement as a corrupt institution because of its intimate dealings with “urban vice.” Following the Progressive era (the 1890s to the 1920s), over a span of five decades, police forces across the country rehabilitated their image on the backs of Black women, as discretionary and largely unchecked police power became widely equated with urban social order. Such mechanisms shaped Black urban politics around policing reform and set the origins of “broken windows” policing. Good cities, or white cities—this book perceptively shows—were not simply those absent of Black people, they were absent of Black working-class women marked as disorderly subjects.

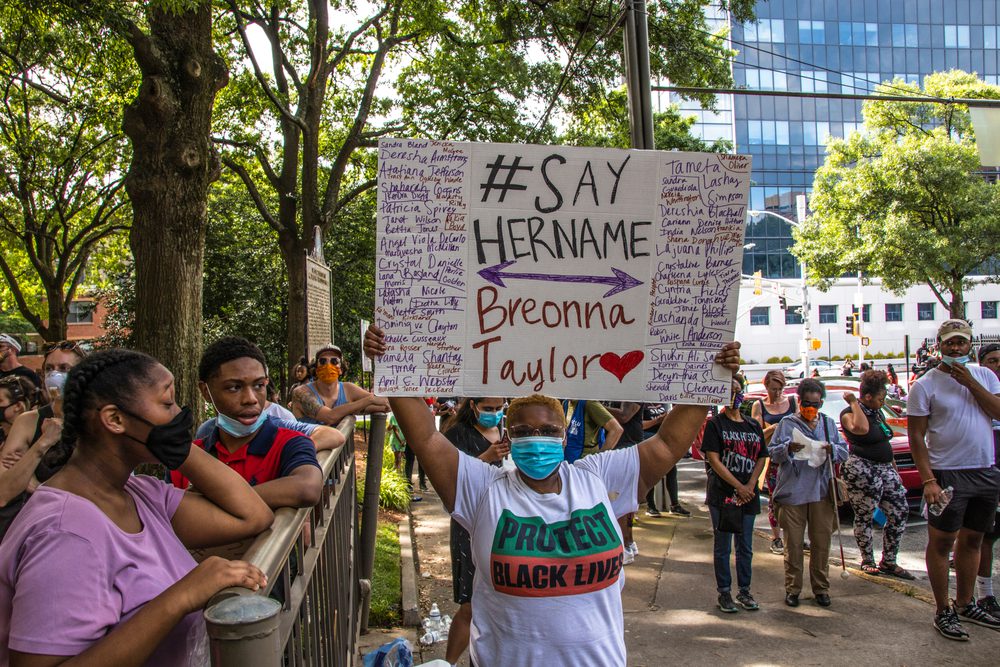

The Streets Belong to Us makes a significant contribution to multiple fields, most principally the history of race, gender, sexuality, incarceration, and state violence in the United States.1 This is a definitive history of the changing, shape-shifting nature of police power, and the ways that it defined, defended and enforced the logics that undergirded racial segregation. The key analytical heft of this work lies in its focus on the centrality of moral laws enforcement in the expansion of police power. Through this framework, this study draws much-needed attention to the calculations implemented—through the courts, through reform, and especially through liberalization— that drove the process by which the public increasingly equated police discretion with neutral arbitration. Those in power made costly decisions about whose sexual behavior remained within the boundaries of the law, those who were likely to act “improperly” or “illegally,” and the locations to be targeted for surveillance and those that were ignored. Illuminating the significant degree to which urban policymaking and planning depended on state violence, Fischer compels us to appreciate more fully the relationship between the making and the remaking of the modern city and the consolidation of police power. To do so, we must see that this connection was made possible through the surveillance, harassment, and sexual criminalization of Black women.

- See, for example: Kali N. Gross, Colored Amazons: Crime, Violence, and Black Women in the City of Brotherly Love, 1880-1910 (2006); Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (2016); Talitha LeFlouria, Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South (2015); LaShawn Harris, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy (2016); Cheryl D. Hicks, Talk With You Like a Woman: African American Women, Justice, and Reform in New York, 1890-1935 (2010); Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America (2016); Naomi Murakawa, The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America (2014); Simon Balto, Occupied Territory: Policing Black Chicago from Red Summer to Black Power (2019); and, Kelly Lytle Hernández, City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los Angeles, 1771-1965 (2017). ↩

So very true it is and have been about controlling black bodies

especially blk women.

I want to research more on this timely topic.