The Great Migration and Black Environmental History: An Interview with Brian McCammack

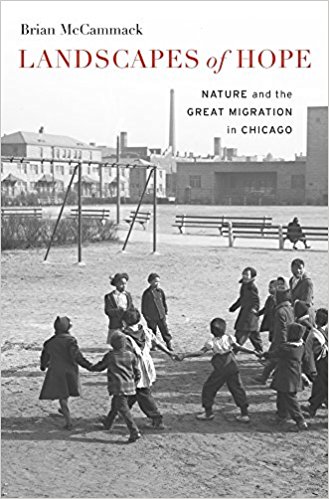

In today’s post, J.T. Roane, Associate Editor at Black Perspectives and an Assistant Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Cincinnati, interviews Brian McCammack on his new book, Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration in Chicago, recently published by Harvard University Press. McCammack is Beerly Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies and Chair of Urban Studies at Lake Forest College, where he teaches courses on African American environmental culture, the Great Migration, American environmental history, and Environmental Politics and Policy. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University’s History of American Civilization Program and was later a fellow at Harvard’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute as well as a Visiting Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies at Williams College. In 2018, Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration in Chicago, was awarded the Organization of American Historians’ Frederick Jackson Turner Award for best first book in American history, the American Society for Environmental History’s George Perkins Marsh Prize for best book in environmental history, and the Foundation for Landscape Studies’ John Brinckerhoff Jackson Book Prize for contribution to landscape studies. He is currently working on a book that examines the origins of the environmental justice movement. Follow him on Twitter @brian_mccammack.

In today’s post, J.T. Roane, Associate Editor at Black Perspectives and an Assistant Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Cincinnati, interviews Brian McCammack on his new book, Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration in Chicago, recently published by Harvard University Press. McCammack is Beerly Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies and Chair of Urban Studies at Lake Forest College, where he teaches courses on African American environmental culture, the Great Migration, American environmental history, and Environmental Politics and Policy. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University’s History of American Civilization Program and was later a fellow at Harvard’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute as well as a Visiting Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies at Williams College. In 2018, Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration in Chicago, was awarded the Organization of American Historians’ Frederick Jackson Turner Award for best first book in American history, the American Society for Environmental History’s George Perkins Marsh Prize for best book in environmental history, and the Foundation for Landscape Studies’ John Brinckerhoff Jackson Book Prize for contribution to landscape studies. He is currently working on a book that examines the origins of the environmental justice movement. Follow him on Twitter @brian_mccammack.

J.T. Roane: You frame your book foremost as a history of the Great Migration. What does your narrative about these spaces of self-fashioning and retreat in the rural Midwest—i.e., beaches, forests, resorts, etc.—add to our understanding of the Migration?

Brian McCammack: One of the main arguments the book makes is that nature needs to join other more well-trodden areas of scholarly research like labor, politics, religion, and education in terms of how and why Southern migrants understood the North as a “Land of Hope” during the Great Migration. An important thread of those Great Migration histories is understanding how black Southerners became modern urban dwellers in cities like Chicago, translating some cultural practices into a new environment and abandoning others. Nature contributes to and challenges our understanding of those more well-known histories, and Landscapes of Hope tracks how migrants forged hybrid environmental cultures that blended elements of South and North. In doing so, I also argue that nature was more than mere backdrop or setting, more than a proxy for broader political struggles. Nature was important to migrants in and of itself—just like good jobs, good education, the freedom to vote, and the like. Migrants expressed that conviction in a range of green spaces both in Chicago and in more rural or wild environments outside the city, and I use a range of cultural texts to show how and why those spaces mattered to a majority-migrant population (between the World Wars, approximately three-quarters of black Chicagoans were Southern-born).

In the more agricultural, more rural South, African Americans tended to know nature through labor and leisure. Many held jobs in Birmingham’s steel mills or Atlanta’s factories, of course, but on the whole there were closer connections to agricultural lifestyles in the South than in a city like Chicago, which was then the nation’s second-largest. In Chicago’s modern industrial economy, residents—whether black or white—understood nature almost entirely through leisure. Evidence of black intellectuals’ thinking along these lines is very apparent. Ida B. Wells, toward the end of her storied career, fights to establish a park in the middle of one of the Black Belt’s most impoverished sections, arguing that it is especially important for working-class children to have those recreational opportunities. W.E.B. Du Bois buys property at Idlewild in northern Michigan (which will become the Midwest’s premiere black leisure resort), arguing not only that it should become a locus of race pride and race activism for the black cultural elite, but also that it’s necessary to restore the bodies, minds, and spirits of urban dwellers weakened by the city’s punishing environment. Chicago clubwoman Irene McCoy Gaines argues that rural youth camps for young African American girls and boys need to be funded to give them experiences in nature that few growing up in the city were fortunate enough to have. Taken together, a picture of nature as integral rather than incidental to the promise of the Great Migration emerges.

Roane: What insights are derived from bringing together the fields of Black history and environmental history? Is there something that changes how we must approach them when we take stock of these fields together?

Roane: What insights are derived from bringing together the fields of Black history and environmental history? Is there something that changes how we must approach them when we take stock of these fields together?

McCammack: Uncovering how and why nature mattered to black migrants puts the African American community in much closer conversation with the environmental movement of the time than is typically understood. You see that nature mattered to black Chicagoans for many of the same reasons it mattered to white conservationists. Americans of all races, ethnicities, and classes were grappling with what it meant to become modern urban dwellers in the interwar era, and nature becomes important as a leisure retreat. Getting away from the city and going “back to nature” for a few days or a few weeks is thought to restore you in mind, body, and spirit, so that you can return to the grind of the city refreshed. The Great Migration, the Forest Preserve District surrounding Chicago, and Idlewild can all trace their origins to the space of just a few years in the mid-1910s; all were important responses to and symptoms of a modernizing, urbanizing world, but they’re rarely put in conversation with one another because environmental and Black history tend to be very distinct, disparate silos.

So what then happens when you layer the more well-researched elements of black urban life in this period—the ways Southern cultural practices were translated into the urban North and the racial violence, segregation, employment discrimination, and so forth that migrants confronted there—onto the emerging American sentiment that nature is a necessary antidote for dealing with the urban environment? When you consider that the urban environment confronting black migrants was much more hostile than that confronting the average white city dweller, you can make the argument—and many black intellectuals do—that nature is an even more important antidote for African Americans.

Roane: Please say something about how archives shaped this project. To what degree was this a matter of returning to sources that historians had already written about and reinterpreting them and to what degree was it a matter of bringing new material into view?

McCammack: The project started out as a reinterpretation of well-known source material like the Illinois Writers Project’s “Negro in Illinois” Papers at the Chicago Public Library. But I was also forced to look to the margins of archival collections in order to bring a coherent story to the center and rely on archivists’ personal knowledge. And finally, I had to draw upon oral histories. Archivists put me in touch with black Chicagoans like Timuel Black, a veritable institution in the city. He has given countless interviews recounting various aspects of his ninety-plus years in Chicago, but I’m not sure anyone had asked him about how nature shaped his experience of the city. Identifying places that seemed formative to black Chicago’s environmental culture and asking pointed questions about them was how his stories about going to the YMCA’s Camp Wabash, witnessing Communist organizing in Washington Park, his brother going on fishing trips—along with stories from a handful of other migrants—made it into the book. It wasn’t a path I’d planned to go down when I began the project, but the lived experiences of nature’s cultural importance to black Chicagoans add so much depth to what can be pieced together from the archive.

Roane: What would you say is the future of Black environmental history?

McCammack: The environmental justice perspective has dominated Black environmental history to this point, and it’s told us a lot about how environmental inequalities are historically produced by forces like housing discrimination. But I think the field is pushing beyond environmental justice to uncover new dimensions of the Black environmental experience. I tend to think of environmental justice insights as a two-sided coin. On one side, African Americans and other people of color have been and continue to be disproportionately exposed to environmental harms like air and water pollution, toxic waste, and the like; Flint’s water crisis is perhaps the most vivid recent example of this. But the flip side is that there’s also disproportionate lack of access to environmental goods like recreation places and so on. The vast majority of environmental justice literature has examined the disproportionate exposure to environmental harms, and that’s absolutely critical in terms of identifying how policies, technologies, and so forth put people of color at risk. But that approach sometimes runs the risk not only of perpetuating a victimization narrative that robs communities of color of agency, but also of losing sight of why those communities valued nature in the first place.

That’s why Landscapes of Hope aims to uncover the multifaceted cultural significance of nature for black Chicagoans, all while not turning a blind eye to the forces of white supremacy that attempted to deny them those environmental goods. We know a lot about the brutal, tenement-dominated landscape—the urban jungle—that Richard Wright depicted in Native Son, for instance, but how does our understanding of the African American experience in Chicago change when you take into account all the elements of urban and ex-urban nature that Wright leaves out? There’s a lot of great work out there that’s pushing in this direction, offering a more comprehensive account of the Black environmental experience—Carolyn Finney’s Black Faces, White Spaces, for instance, and Kevin Dawson’s Undercurrents of Power. Walter Johnson’s River of Dark Dreams is also a compelling example of how Black environmental history can be tied to a range of other historiographies like the histories of capitalism and slavery.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.