Steeped in the Blood: On The May 15th, 1970 Jackson State Killings

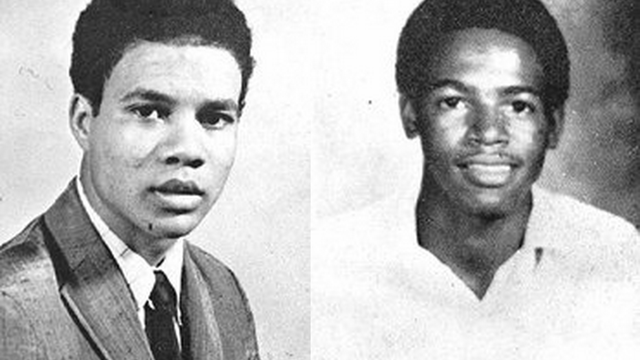

On the night of May 14, 1970, Phillip Gibbs and James Earl Green made their way to Alexander Hall, a women’s dormitory, on the campus of Jackson State College. Although a protest was taking place down the street, in which a dump truck was set on fire, the two young men were on campus to pay social calls. In the early morning hours of May 15, a group of law enforcement officers approached the students standing outside the building, which included Gibbs and Green, firing upon the congregation after a bottle crashed behind the armed men. Separated by a chain link fence, the unarmed students did not pose a direct threat to police officers, yet notions of Black criminality, white racism, and an effort to preserve order created an atmosphere of danger. In the end, Gibbs and Green were both killed, while twelve others suffered injuries as a result of the shooting. The tragic events in Jackson, however, were overshadowed by the shooting at Kent State University nearly two weeks earlier, the latter standing out in historical memory as the primary example of violence that occurred during the student movement of the 1960s and 70s.

Historian Nancy K. Bristow’s Steeped in the Blood of Racism: Black Power, Law and Order and the 1970 Shooting at Jackson State College explores the relationship between Black Power activism, racially-coded notions of law and order, and the shooting at Jackson State College in 1970. Bristow argues that demands for law and order, from Washington, D.C. to Jackson, Mississippi, intensified during the era of Black student activism, which, in turn, resulted in the shooting at Jackson State College. The race-neutral appeal to maintain order in a society undergoing social transformation was part of the broader campaign of resistance to Black civil rights and the preservation of white supremacy in the mid-twentieth-century. For many white Americans, it felt as though their country was unraveling due to the concurrent social movements of the time. The logical response to anti-war protestors, Black Power advocates, and student activists, according to President Richard Nixon and his supporters, was to minimize violence by acting violently towards these groups. In Bristow’s work, the author claims that it was only a matter of time before Black students became the victims of an idea that supported violence against Black communities.

The structure of Steeped in the Blood of Racism is a notable strength. Bristow, who describes the night of May 14 and early morning of May 15 in chapter three, frames this study as a before and after re-telling of events. Bristow contextualizes race relations prior the Jackson State College shooting by examining Black protest, the white massive resistance campaign to civil rights, and the role of state-sanctioned violence in Mississippi. Specifically, Bristow explains the shift in leadership at Jackson State College, from accommodationist Jacob Reddix to the Afro-centric style of John A. Peoples, to show how Black Power developed on the Jackson State College campus. Bristow writes that conditions within the state of Mississippi, long-known for anti-Black racism, empowered white police officers to respond violently to non-violent students. The latter half of the book is framed by the immediate aftermath and historical memory of the May 1970 shooting. According to Bristow, three competing claims emerged following the event: a color-blind interpretation of student suppression; the shooting as an example of state-sanctioned racial violence; and the law and order narrative that many white Mississippians supported. In the end, when police officers failed to be charged and the victims of the shooting were not compensated for their loss, the law and order ideology prevailed in Mississippi’s legal realm and the court of public opinion.

Bristow’s well-researched study and important claims are supported by oral interviews, legal depositions, and archival material from the civil rights era. Each form of source material plays an important role in the construction of the narrative, as these sources illuminate multiple perspectives of the Jackson State College shooting. The oral interviews are particularly important in capturing the voices of those who witnessed or were involved in the white police officers’ attack on Black students. These interviews, many of which are conducted by Bristow over the course of four years, describe the emotions of Jackson State students during and after this life-altering event. The legal depositions recount the criminal and civil trials that took place after the shooting. Bristow uses these court records as the basis for the three competing narratives that formed in the subsequent years and shaped the Jackson State College tragedy in historical memory. Bristow’s well-balanced account stems from her ability to frame this study in a way that appeals to general audiences while offering a study that is intellectually stimulating for scholars.

This account of the Jackson State College shootings, however, has a drawback. Throughout the book, the author tries to separate the events at Jackson State and Kent State, yet Bristow continually reinforces the connection of these two occurrences. Acknowledging that Jackson State and Kent State are forever linked due to their chronological proximity, Bristow emphasizes the role of race in the Jackson State shooting, which was not an element present at Kent State. With so much attention to an event that occurred at the same time, but as a result of different circumstances, Steeped in the Blood Racism explains important distinctions between Jackson State and Kent State, while sometimes unintentionally supporting the historical link between the shootings. Despite this criticism, Bristow’s contribution not only illuminates an often-overlooked event in the history of state-sanctioned violence against Black Americans, it provides a much-needed historical explanation of contemporary social and political issues.

In addition to Tim Spofford’s Lynch Street: The May 1970 Slaying at Jackson State College, Bristow’s Steeped in the Blood of Racism is only the second book-length source on the Jackson State shooting. Fifty years after the shooting, Bristow provides an important addition to scholarship on Jackson State, in particular, and the recent history of the criminal justice system overall. Although Bristow provides little attention to mass incarceration in this book, the law and order narrative provides an important contribution to the rise of the carceral state. While Bristow applies law and order to student demonstrations, other scholars have examined the growth of the criminal justice system alongside the expansion of civil rights for Black Americans. The philosophical reasoning for law and order is at the center of Bristow’s work, capturing varying degrees of the racial dynamics of incarceration to, in this case, state-sanctioned violence and the killing of innocent people.

Bristow’s account of the Jackson State College shooting resonates with audiences fifty-years later because of its contemporary relevance. Violence against Black bodies at the hands of police officers has garnered more attention from news outlets, social media, and academics in recent years, especially within the context of an expanding carceral state. It is not a coincidence, Bristow and others argue, that rhetoric supporting law and order increased alongside the growth of Black Power in America. Today, many Americans use law and order to justify the killing of people of color at the hands of both law enforcement and “vigilant” citizens. Therefore, Bristow’s timely work describes a brutal chapter in the racially-coded history of law and order, a philosophical belief that seeks to emphasize social health over the racist regulation of behavior, but disproportionately effects communities of color.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.