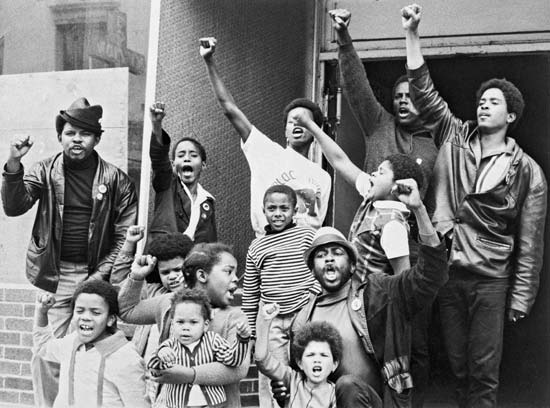

State Repression, Gender, and the Black Panthers

This post is part of our online roundtable on Robyn Spencer’s The Revolution Has Come

In 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale penned the Black Panther Party’s (BPP) Ten-Point Program, which not only governed the organization for nearly two decades, but has come to symbolize its most enduring intellectual legacy. Point five read, “we want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present-day society” (my emphasis). Robyn Spencer’s The Revolution Has Come is an answer to that call. She notes that she wanted “readers to know what it meant to live inside an organization that considered itself revolutionary” (p. 202). By giving attention to women and rank-and-file members; highlighting how personal struggles over housework, collective living, and leisure were crucial political questions; and reframing state repression as a molder of strategy and not simply a matter of degree, Spencer offers up new lessons from Black Power’s most heralded and scrutinized group. As she points out, communities today often search for leaders, not organizations. The history of the Panthers in Oakland reminds us of the need for sustained local organizing that is a “sum greater than its parts” (p. 202).

The Panthers were born of local experiences of the Oakland black community with dislocations caused by so-called “urban renewal” and the loss of the industrial and waterfront jobs that had brought so many westward during World War II. In addition to these local conditions, the formation of the Panthers was shaped by what Spencer calls the “connective tissue linking protests nationwide” (p. 22). Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in April 1968 and Bobby Hutton’s death at the hands of police following a shootout with police just days later also marked a turning point in the history of the Panthers. Both “seemed to confirm the futility of nonviolence” (p. 62). However, that futility did not signal universal agreement on where to go next. The year 1968 marked the beginning of an era marred by state repression and harassment by local police, a legacy that is complicated in its meanings for the future and the form of the Black Panther Party. One of the most significant contributions of Spencer’s work lies in her discussion of the impact of state repression on the organization’s growth, which might sound surprising given that accounts focusing on government intervention have been ubiquitous since the first waves of Panther historiography. Spencer importantly pivots the question away from whether or not the government was responsible for the organization’s demise to focus on the ways it fundamentally changed the Party’s direction. She writes that “repression didn’t just aim to kill; it aimed to shape how the organization lived” (p. 90).

The former aim is empirically without doubt. According to the Party, members were arrested 739 times during 1968 and 1969, and the organization paid nearly $5 million in bail over that period. But to illustrate the latter point, Spencer points to Huey Newton’s open letter circulated just ten days after his release from prison. Newton expressed solidarity with gay and women’s liberation movements and argued for the creation of a “revolutionary value system” that would form coalitions with, and create space for leadership by, such groups. When his letter created backlash within the party, the FBI seized upon this discord and stoked it to further these divisions within the leadership. In this sense, potential alliances, as well as support for women’s leadership and gays and lesbians within the party, were quickly abridged through coercion and interference by the FBI. Yet, state repression also opened avenues for the expansion of women’s roles within the organization. “The fact that women became the majority of the organization’s membership by 1969 shaped how repression and gender intersected,” Spencer argues. “Recasting the story of COINTELPRO through the lives of women makes its organizational impact more visible” (p. 89). At the heart of the early history of the Panthers is a set of debates surrounding political strategy in response to, and in dialogue with, intense government surveillance and subterfuge.

Moreover, the party’s community survival programs emerged in response to this repression, which has been well documented elsewhere. As the Panthers shifted towards creating a sustainable and lasting institution in Oakland, the Black Panther paper ironically moved away from organizational news and towards national and international happenings. In other words, to build a more sustainable internal infrastructure, the organization needed to face externally. As Spencer delves into the survival programs and the Black Panther Party after the years of its most intense repression, we get the deepest and richest sense of what life looked like for a rank-and-file member. For example, in 1973, a survey of 119 Panthers revealed roughly equal numbers of men and women members, with an average age of twenty-and-a-half. They were primarily factory workers, clerks, office workers, or employed in poverty programs. Some were students, and some were on parole, probation, or welfare.

But rather than focus on declension through the trappings of a charismatic figure like Huey Newton—a trope in Panther literature as exemplified by Hugh Pearson’s The Shadow of the Panther—Spencer explores the Party’s decline through the voices of these rank-and-file members by examining inner-party memoranda and correspondence. These documents reveal the imbalanced workload of women within the party, the grueling schedule for families with children, the decline of political education as a centerpiece of the organization, and the feelings of deep social isolation experienced by some members. By elevating these concerns, Spencer shows the decline of the organization not through the idiosyncrasies of a particular leader, but through an organizational structure that suppressed group dissent by elevating a few voices over many.

Despite an attention to local and national conditions in the opening chapter, we get less of a sense of the local political milieu of the Bay Area, as well as the changing character of nationwide organizing, as the book progresses. A pressing question remains: what did the story of the Oakland Black Panther Party mean to Black Power and other radical movements? Spencer’s account sometimes submerges the ways in which the Panthers drew from the Nation of Islam, the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), and other black nationalist organizations. It has become axiomatic to cite Malcolm X as an intellectual progenitor, and Spencer importantly notes that Newton and Seale went to see Malcolm speak and attended local mosques in the Bay Area. The organizational lessons the Panthers took from these other groups remains under-theorized, however. For example, she writes, “it took only a short time [for Newton and Seale] to create the founding principles and a statement of goals of their ten-point platform and program” (p. 31).

Yet this is in part because their “What We Want! What We Believe!” program was modeled closely after the NOI’s “What the Muslims Want, What the Muslims Believe,” which was reprinted at the end of each issue of Muhammad Speaks. Similarly, Bobby Seale wrote to the OAAU offices in Harlem in 1964 asking for a subscription to its Blacklash newsletter, noting his interest in “the liberation of all black people the world over.”1 While suggestive and not authoritative, this evidence points to more than engagement with Malcolm X as a solitary figure and towards institutional and organizational pathways that shaped the Panther Party at its inception and throughout its development.

Nonetheless, The Revolution Has Come raises important questions about social movement organizing then and now, including the role of government repression in fomenting and publicizing, subverting and draining, and fundamentally channeling and altering radical political movements. How does viewing state repression through the lens of gender reshape our ideas about gendered political labor and thought (i.e. self-defense as masculine, free breakfast programs as feminine)? How do histories of organizations, rather than leaders, enable us to envision new forms of freedom struggle? What is the role of political education in sustained community organizing? How do anti-capitalist and anti-racist organizations function within a racist capitalist society? Or, as one Panther queried, “How can we as revolutionaries hope to administer thousands perhaps millions one day through the city, state or federal governments when we don’t have the financial self-reliance to manage our personal money?” (p. 198).

Lastly, what does a revolution look like? Just before his death in 1965, Malcolm X called the greatest mistake of the Civil Rights Movement “trying to organize a sleeping people around specific goals. You have to wake the people up first, then you’ll get action.” He presciently argued, “blacks must take the lead in their fight. In phase one, the whites led. We’re going into phase two.”2 The story of the Black Panther Party in Oakland is a powerful account of this phase two and the immense threat it represented to those in power. Spencer’s treatment of that story gracefully achieves her lofty goal of capturing what it meant to “experience comradeship, to feel the joy that came with a deep political commitment, and to feel the agony of betrayal by people, ideas, and the very organization they were committed to” (p. 202–203).