Resurrecting the Radical Pedagogy of the Black Panther Party

Not long ago I had the opportunity to visit The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture’s Black Power! exhibition, an unforgettable retrospective commemorating the legacy of the Black Power movement on the occasion of its 50th anniversary. Located at the corner of West 135th St. & Malcolm X Blvd. in Harlem, the exhibit runs until December 2017 and showcases photographs, memorabilia, and oral histories honoring Black freedom fighters such as Angela Davis, Amiri Baraka, Huey P. Newton, Kathleen Cleaver, Sonia Sanchez, Emory Douglas, Ericka Huggins, and countless others. To date, close to 10,000 visitors have spent some time at the Black Power! exhibition, learning about “the heterogeneous and ideologically diverse global movement that shaped black consciousness and built an immense legacy of community organizing and advocacy that continues to resonate in the United States of America and around the world today.”

The exhibition itself is organized around nine categories of inquiry, each of which is represented within a particular section of the Center’s lavender garbed gallery: Organizations, Political Prisoners, Coalitions, Education, The Look, Pop Culture, Black Arts Movement, Spreading the Word, and Black Power International.

As I meandered from theme to theme in the newly-renovated Main Hall, I found myself returning to the exhibition’s section on education. I began to wonder what critical educators today could learn from the types of radical pedagogies imagined by architects of the Black Power movement. And so as I stood face-to-face with Emory Douglas’s iconic May 11, 1969 “Black Studies” illustration, I wrote out a few significant questions: To what extent do today’s educational spaces serve as sites of liberation? How can we, as transgressive educators interested in questions of Blackness, power, history, and resistance, incorporate an emancipatory, Panther-inspired pedagogies into our own teaching? And finally, what can we learn from non-traditional educational institutions like the Black Panther Party’s Intercommunal Youth Institute/Oakland Community School?

***

Drawing inspiration from the Highlander Folk School (1932-present), Citizenship Schools (1957-1965), and Freedom Schools (Summer 1964), the founding members of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP) believed that a learner-driven, politically relevant, and transgressive education that empowers youth to expose the existential contradictions of their own lives creates the conditions necessary for a world in which both Black and non-Black liberation is possible.

In late-October 1966, 30-year-old Bobby Seale and 24-year-old Huey Newton drafted what would become the Black Panther Party’s Ten-Point Program. Beyond demanding “an immediate end to police brutality and murder of black people,” arguably the early core impetus for the Panthers’ founding, Seale and Newton explicitly insisted upon “education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society [and] that teaches us our true history and our role in the present-day society.” In conjunction, they demanded “an educational system that will give our people a knowledge of self [because] if a [person] does not have knowledge of [themselves] and [their] position in society and the world, then [they have] little chance to relate to anything else.”

Newton, in fact, argued that “the main function of the party is to awaken the people and teach them the strategic method of resisting the power structure.” Given his contention, what might a Panther-inspired pedagogy have to do with “resisting the power structure” today? And how might radical educators apply the BPP’s pedagogy, in the words of Robin D.G. Kelley, in service of challenging the “crisis of political education” within the university and beyond?

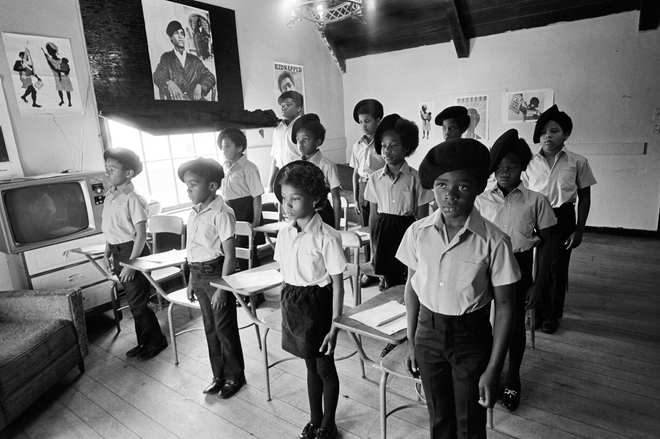

The BPP launched its Liberation School initiative in 1969, according to Bobby Seale, as a “supplement to the existing institutions, which still teach racism to children, both black and white.” The supplementary—if doctrinaire—nature of Liberation Schools would eventually give way to the BPP’s Intercommunal Youth Institute (IYI) in 1971, an alternative educational institution intended to equip youth with the cultural, political, and analytic resources to understand themselves as local-global subjects in a world undergoing transformation.

Without invoking it by name, the Panthers were drawing on what Brazilian educator Paulo Freire might call a “pedagogy of the oppressed” that “culminates in transformative action upon the world.” Freire writes that “liberation is praxis: the action and reflection of [people] upon their world in order to transform it.” Conscienization, as Freire terms it, is not an exercise in intellectual calisthenics but rather entails “the process of cultivating a critical consciousness through education [and] must begin from the perspective of a person existing in and with the world.” Newton’s rendering of the Panther’s IYI is strikingly consistent with Freire:

The institution’s primary task, then, is not so much to transmit a received doctrine from past experience as to provide the young with the ability and technical training that will make it possible for them to evaluate their heritage for themselves; to translate what is known into their own experiences and thus discover more reality their own.

Located in a North Oakland house, the inaugural 25-member IYI student cohort consisted predominantly of BPP members’ children. Students ranged from 2.5 to 11 years old. Erica Huggins, director of the school from 1974-1981 explains: “We start at age 2.5 because we do believe that a child doesn’t have to be 5 in order to form concepts. So, they learn a lot of things at an early age.”

In 1973, IYI added political education, physic education, music, and people’s art (taught by Emory Douglas, the BPP’s Minister of Culture) to its curriculum. The school embraced an “each one, teach one” ethos where teacher-students and student-teachers “work collectively in order to develop an understanding of solidarity and camaraderie in a practical way.” That year, the IYI relocated to larger facilities in East Oakland in order to meet student demand. The new facility included a curriculum center, art room, 8 classrooms, a fully equipped kitchen, and a 300-seat auditorium. Enrollment increased to 42.

The following year, Ericka Huggins and other BPP leaders renamed the IYI the Oakland Community School (OCS) because, according to Huggins, “Intercommunal Youth Institute sounded exclusive.” That year enrollment rose to 110 students and the school began charging a non-mandatory $25 tuition. The OCS’s operations were funded primary by grants, fund raising activities, and private donations.

By 1975, the OCS began working with graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and Santa Cruz and other area universities to assist with curriculum development. Classroom instruction was supplemented with weekly field trips, when possible, to visit the political trials of Panther members, including the San Quentin 6, to “acquire direct exposure to the inadequacies of the American judicial system for Black and other minority people.” By 1976, the school had a waiting list of over 400 students and “children enrolled in the school [were found to perform] 3-4 years in advance of their public peers.”

On August 18, 1977, party members were invited to the California state Legislature in Sacramento to accept an award for their work with the OCS. State legislators passed a resolution lauding the school for its superlative service to the children of Oakland: “Resolved; that the highest commendations be extended to the Oakland Community School for its outstanding record of dedicated and highly effective service in educating the children of the community of East Oakland.” Though OCS closed its doors in 1982 due to financial trouble resulting from accusations of embezzlement by party leadership, the IYI/OCS’s 11-year tenure not only provides an inspiring example of liberatory education and critical pedagogy in action but demonstrates with unimpeachable clarity the fact that a radical political education, as some argue, need not come at the expense of what Huey Newton calls “technical training.”

From mixed-age horizontal classroom relationships between student-teachers and teacher-students, to experiential and embodied learning opportunities in the local community and the prioritization of art, resistance, and service, the BPP’s pedagogy was truly at a vanguard of a burgeoning Black freedom-centered educational movement. My sincere hope is that as educators we will look to the Panthers for inspiration in our own classrooms, for, as Robin D.G. Kelley writes in Freedom Dreams, “The most radical ideas often grow out of a concrete intellectual engagement with the problems of aggrieved populations confronting systems of oppression.” If we start with this premise, then perhaps we can begin to equip our students with the resources necessary to “evaluate their heritage for themselves” and demand a world that affirms their existence and ushers in the type of political transformation befitting of the Panthers’ vision of freedom.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.