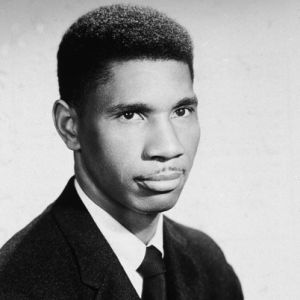

Medgar Evers’s Legacy of Organizing in Mississippi

Although Medgar Evers is one of the most widely recognized figures of the Civil Rights Movement, many people do not know what he actually did. All too often, Evers’s first appearances in movement histories emerge on the night of his murder, June 11, 1963. But Medgar Evers had an incredible eleven-year career as a civil rights activist long before he was struck down in his Jackson driveway. The groundwork he laid during that time was essential for Mississippi activists in the years after his death.

Born in Decatur, Mississippi on July 2, 1925, Medgar Evers was the son of two enterprising parents who stressed financial independence and education. As a boy, Evers grew up reading copies of his parents’ Chicago Defender, which helped him gain a better sense of Black politics beyond Mississippi. In 1943, Evers joined the Army and later used the G.I. Bill to attend Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Alcorn State University), where he thrived as a campus leader and student-athlete. Upon graduation in 1952, Evers accepted a position with the Black-owned Magnolia Mutual Insurance Company in the Mississippi Delta. Soon thereafter, he became involved with the local NAACP and another organization named the Regional Council for Negro Leadership.1

Evers appeared on the national NAACP’s radar in 1954 when he applied to law school at the University of Mississippi. After his application was rejected, Evers considered suing for admission but ultimately decided against further action. Representatives from the national NAACP, which counseled Evers as his application was pending, were so impressed by the young activist that they recommended the organization hire Evers as their first Mississippi Field Secretary. It was in this role that Medgar Evers truly made his most lasting contributions to the movement.2

As NAACP Mississippi Field Secretary between 1954 and 1963, Evers was responsible for a wide range of duties. He investigated dozens of cases of racial violence and discrimination, including the murders of Emmett Till, George Lee, J.E. Evanston, Timothy Hudson, and Clinton Melton, and the wrongful imprisonment of Clyde Kennard. Evers also collected affidavits from Black Mississippians who had been denied the right to vote and helped prepare several voting rights activists to testify in front of Congress during hearings related to the legislation that would eventually lead to the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960. This evidence helped prove racially-discriminatory voter registration practices that demonstrated the need for more comprehensive voting rights legislation in the South. In addition to these duties, Evers also served as a conduit between the national NAACP and Mississippi activists who desperately needed financial and legal assistance because of repercussions they faced for their activism.

Medgar Evers’s least visible, yet perhaps most important, contribution to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s was the creation of an underground network of NAACP activists across Mississippi. On top of his formal duties, Evers was a relentless grassroots organizer who spent much of his time driving to covert meetings across the state with a .38 special in his glove box. During his first three years as field secretary, Evers drove over 42,769 miles in his Oldsmobile.3

Because of the dangers of civil rights activism in Mississippi, Evers did not maintain detailed minutes of these stealthy meetings. Records indicate who signed affidavits or requested financial support, but most details of these small gatherings are lost to history. What is clear, however, is that Evers travelled to nearly all corners of Mississippi to meet with small groups of extremely dedicated NAACP leaders in church basements and the backrooms of Black businesses. In an era when NAACP officials were increasingly targeted, his bravery in undertaking this type of activism cannot be overstated. Thurgood Marshall appropriately remembered that Evers had “more courage than anybody I’ve ever ran across.”4

Between 1955 and 1958, Mississippi’s NAACP membership actually declined from 4,639 to 1,436. “It is not the lack of interest,” Evers reported, “but fear.” Nevertheless, those remaining members comprised an increasingly strong and well-connected core of financially independent local civic leaders. As longtime Evers ally Aaron Henry of Clarksdale recalled, “The years from 1956 to 1961, although relatively calm, marked significant advancement for us.”5

The root of that advancement lie in Medgar Evers’s expanding Mississippi NAACP network. In addition to small private meetings, Evers also worked to ensure that NAACP branch leaders could meet and communicate. To facilitate networking among NAACP branch leaders, Evers held annual meetings in Jackson and intermittent gatherings at rotating regional sites across the state. “Medgar knew,” described his close ally Ed King, “the importance of their communicating with each other.” Through these meetings, NAACP leaders from places such as the Delta, Jackson, the Piney Woods, and Gulf Coast met to exchange ideas and contact information. It was a small but dedicated network of hardcore activists. “Those were people,” remembered Ed King, “who sort of had said, ‘when the fullness of time comes I’ll be ready.’”6

When Bob Moses of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee first arrived in Mississippi in the summer of 1960, he stayed in the home of a longtime Medgar Evers NAACP ally named Amzie Moore of Cleveland. During that time, Moses came to realize that “Amzie was connected throughout the state.” When SNCC entered Mississippi full-time the following year, the organization moved from Moore in Cleveland to C.C. Bryant in McComb to Vernon Dahmer in Hattiesburg and then back into the Delta where they worked with Aaron Henry. SNCC’s expansion into Mississippi operated along the network of local NAACP activists Medgar Evers developed in the late-1950s.7

Ultimately, SNCC managed to create a remarkable statewide grassroots organizing campaign that brought people like Fannie Lou Hamer, Hollis Watkins, Victoria Gray into the movement and led to iconic campaigns such as the Mississippi Freedom Vote, the 1964 Freedom Summer, and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party convention challenge in Atlantic City. Medgar Evers did not live to see the full fruits of his organizing efforts, but the NAACP network he developed in the late-1950s helped pave the way for so much activism to emerge out of Mississippi in the 1960s.

- Evers and Andrew Szanton, Have No Fear: The Charles Evers Story (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1997), especially 1-44; Myrlie Evers with William Peters, For Us, the Living (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1996, orig., 1967), 1-33; and Michael Vinson Williams, Medgar Evers: Mississippi Martyr (Fayetteville, AK: University of Arkansas Press, 2011), especially 13-83. ↩

- Williams, Medgar Evers, 55-83; and Myrlie Evers-Williams and Manning Marble, eds., The Autobiography of Medgar Evers (New York: Basic Books, 2005), 3-16. ↩

- Myrlie Evers, “He Said He Wouldn’t Mind Dying—If…” Life, June 28, 1963, 35-37; Medgar Evers, “1955 Annual Report Mississippi State Office NAACP,” Box 2, Folder 39, Evers Papers. Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, MS; Medgar Evers, “1956 Annual Report Mississippi State Office NAACP,” Box 2, Folder 39, Evers Papers; Medgar Evers, “1957 Annual Report Mississippi State Office NAACP,” Box 2, Folder 39, Evers Papers; Evers, For Us; and Colia Clark, interview by author, recording, New York City, July 7, 2010, in author’s possession. ↩

- Evers, For Us, 184-234; Williams, Medgar Evers, 85-170; and Mark Tushnet, ed., Thurgood Marshall: His Speeches, Writings, Arguments, Opinions, and Reminiscences (Chicago, IL: Lawrence Hill Books, 2001), quoted on 510. ↩

- Medgar Evers, “1955 Annual Report Mississippi State Office NAACP,” Box 2, Folder 39, Evers Papers; Medgar Evers, “1957 Annual Report Mississippi State Office NAACP,” Box 2, Folder 39, Evers Papers; Williams, Medgar Evers, 85-116, Evers quoted on 144; and Aaron Henry with Constance Curry, Aaron Henry: The Fire Ever Burning (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2000), quoted on 110. ↩

- Ed King interview by author, recording, Jackson, MS, March 27, 2010, in author’s possession; and regional and statewide meeting correspondence found in Box 5, Folder 1, Amzie Moore Papers, 1941-1970, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI. ↩

- Bob Moses, interview by author, Jackson, MS, March 27, 2010, recording in author’s possession. ↩