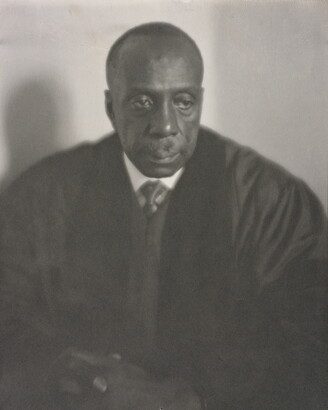

Howard Thurman and the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples

This post is part of our forum on Howard Thurman and the Civil Rights Movement.

In a 1978 Ebony profile famed journalist Lerone Bennett argued that Howard Thurman “was more than an activist, he was an activator of activists a mover of movers.”1This dynamic began with his work at Howard University, where he acted as a mentor for some of the leading movement figures, including Pauli Murray and James Farmer. His friendship with Martin Luther King, Jr. profoundly shaped the civil rights leader’s views. Less well known was Thurman’s pioneering work creating the Fellowship Church of All Peoples, which deeply influenced mid-century liberal Protestantism.

Howard Thurman came of age just as Gandhi’s teachings began to influence the Christian Left. Born in 1899 Thurman grew up in the starkly segregated community of Daytona Beach, Florida, where he witnessed brutal racial violence and saw the impact of disenfranchisement on the Black community. From there he attended Morehouse College in Atlanta alongside Martin Luther King, Jr.’s father, graduating as valedictorian in 1923. After his ordination as a Baptist minister Thurman continued his studies at Rochester Theological Seminary, where he was the only African American student. In Western New York he encountered an active KKK presence, disabusing him of the belief that racism was regionally limited. He remembered later that “within the Christian church, the pattern of segregation was effective without regard particularly to the section of the country in which the church was located. North or South, it made no difference. This was new to me [italics in the original].”

Thurman left Rochester to accept a position as pastor at a Baptist church in the liberal enclave of Oberlin, Ohio. After several years in this position, Mordecai Johnson, Dean of Howard University, hired the young man as a faculty member and Dean of Rankin Chapel. Because of Thurman’s prominence in pacifist circles, as well as his growing reputation as a religious thinker, the YMCA’s Student Christian Movement gave him the opportunity to travel to India in 1935. The small group visited fifty-three cities and Thurman spoke at dozens of colleges and other public venues. During these appearances South Asian audiences repeatedly challenged Thurman to defend Christianity’s teachings given the reality of racial segregation and white violence. These conversations inspired Thurman to later write his most famous book, Jesus and the Disinherited. But the trip’s most memorable moment was a three-hour private meeting with Gandhi at his retreat in Bardoli, India. It was there Gandhi declared, “It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of non-violence will be delivered to the world.”2

After his meeting with Gandhi, Thurman continued his travels in South Asia and experienced a vision while gazing at the Khyber Pass from Pakistan. At this place of great beauty Thurman was overcome with the power of history and religion. In his autobiography Thurman wrote that he knew “we must test whether a religious fellowship could be developed in America that was capable of cutting across all racial barriers, with a carry-over into the common life, a fellowship that would alter the behavior patterns of those involved.” Thurman spent the rest of the decade searching for this opportunity and seeking to make his religious leadership at Howard a model of ecumenical and mystical fellowship. In 1943 an invitation to lead an interracial church allowed Thurman to fulfill this vision.

The invitation came from Albert Fisk, a progressive white minister who sought to build an interracial church in San Francisco. Soon Thurman arrived in the city with his wife Sue Baily Thurman and their two daughters. Thurman immediately applied his theological and social ideals to the church, which he saw as “a creative experiment in interracial and in cultural communion, deriving its inspiration from a spiritual interpretation of the meaning of life and the dignity of man.” Initially the church served the surrounding neighborhood, which was primarily made up of African American migrants, and it was known as the “Neighborhood Church.” But after moving twice to accommodate the growing congregation in 1949 they settled in a relatively large building on Larkin Street, where the church remains today. The initial congregation numbered only thirty, and five years later two hundred congregants attended the weekly services. The rapid growth of the Fellowship church suggests Thurman’s ecumenical message of full racial equality found fertile ground in San Francisco.

As the church grew its programs became increasingly experimental. While still at Howard Thurman developed liturgical forms that he hoped would help connect congregants with a spiritual force that united humanity. He began services with a half hour of silent meditation, a practice that reflected the teachings of Rufus Jones and other mystics, as well as Eastern religious teachings. The church also set aside a room for meditation, supplied with books and figures from a variety of religious traditions. At Howard Thurman also experimented with using alternative forms of worship including reproducing living tableaus of religious paintings and incorporating modern dance interpretations of spiritual teachings into services. He brought these practices with him to San Francisco and encouraged his congregants to explore the aesthetics of spirituality beyond reading scripture or studying traditional theology. Thurman’s goal was to create an environment in which congregants could experience mysticism and the presence of God outside the constraints of mainstream Protestantism. Given the diversity of congregants, which also included Mexican, Chinese, and Filipino immigrants, Thurman and Fisk always emphasized the theme of unity and brotherhood.

Curious reformers and activists routinely visited the Fellowship Church, often becoming part of a growing network of affiliates who did not live in the city. In 1945, for example, W.E.B. DuBois visited and spoke at the church while in the city for a United Nations conference on the topic “The World Peace and the Darker Peoples.” Soon after he devoted his “Winds of Time” column in the Chicago Defender to praising the work that Thurman was doing. Mordecai Johnson, Thurman’s former boss at Howard University traveled to the West Coast and preached at the Fellowship church in 1945. Josephine Baker, the performer and international civil rights activist, also visited as did the South African novelist, Alan Paton. The international nature of this support reflected the global nature of pacifism and the Christian Left. These dignitaries could also follow news of the Fellowship Church in the press, which was fascinated with this interracial experiment. Time magazine did a major story on the church in 1948 and other major publications, including Ebony and Life, followed with feature articles.

As it grew in popularity, the Fellowship Church spawned imitators in several cities. Homer A. Jack, a white Unitarian minister and one of the Congress of Racial Equality’s founding members, declared “the emergence of the interracial church” in 1947. In Detroit the white Unitarian minister Ellsworth M. Smith opened an interracial Church of All Peoples in 1945. In addition to the Detroit church, Jack cited the Fellowship House’s religious services in Philadelphia, and its imitators in Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and New York. Congregational churches in Berkeley and Chicago were also explicitly interracial. The largest church, and the one most resembling Thurman’s congregation, was the Church of All Peoples in Los Angeles. Thus, Thurman was part of a larger movement of liberal interracialism and a powerful Christian Left.

Thurman left his San Francisco pastorate to become Dean of the Chapel at Boston University in 1954. Thurman felt that his work in San Francisco had come to a natural end and he was ready to take on a new challenge. “By 1954 not only was the United Nations established and at work on many of its problems,” wrote Thurman in his autobiography, “but in that very year a scant sixty days before the celebration of our Tenth Anniversary, the historic decision of the United States Supreme Court on integration in public education was handed down. All of this is to indicate that the origin and development of Fellowship Church were part of a world-wide ferment of which many people were increasingly aware.” Thurman had succeeded in creating the church he first envisioned while gazing at the Khyber Pass nearly two decades before. And he believed there was an increasing understanding of the promise of racial equality on a global scale. Thurman’s teachings were deeply influential in the Christian Left and sustained a generation of activists as they developed a new set of tactics to defeat segregation. And the people of San Francisco continued to support the church Thurman helped build long after he left for Boston. Indeed, it remains today, its interracial congregation providing an oasis in a city that has become a global symbol of inequality.

Thank you for your beautiful recounting of Dr Thurman’s inspirational life. His vision and practice have long touched my soul as a way to center my own work in social Justice. These details about the pathways to the development of his theories provides an important context for understanding his profound contribution to the overarching themes during the 1950’s through today in the many struggles for civil rights in the US and internationally. Thank you again.