Dismantling Whiteness as the Beauty Standard

Miss Jamaica Davina Bennett rejected Eurocentric beauty ideals when she sported her afro at this year’s Miss Universe Pageant. Bennett had long crowned herself with her afro style and insisted on wearing her natural hair to challenge beauty stereotypes. The Miss Universe pageant offered a platform to confront beauty ideals and radiate self-love and acceptance for Black girls and women. We should not take lightly the symbolic weight of Bennett’s rejection of a straight hairstyle in favor of her natural texture.

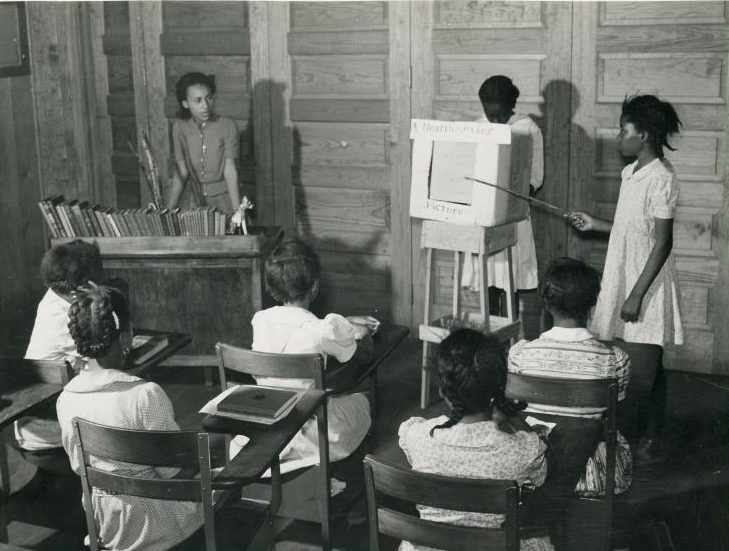

Many of us are familiar with the study done by psychologists Kenneth B. Clark and Mamie K. Phipps Clark in the 1930s and 1940s. The Clarks conducted The Doll Test in which they invited children to describe various dolls. Black children across America consistently, though not entirely, identified Black and brown dolls as ugly, while describing white ones as “pretty,” “clean,” and “nice.” Although European designation of Blackness as ugly has a long and complex history, “it was within the context of modern slavery in the Americas,” the late historian Stephanie Camp argued, “that African and black bodies came to be seen as singularly and uniformly ugly.”

As the transatlantic slave trade expanded and New World colonies engineered their dependence on the life and labor of enslaved Africans, Europeans created theories to malign the culture and beauty of African descended people to justify enslaving and exploiting them. By singling out cultural differences and physical traits such as skin color and hair texture, Europeans defined Africans and their descendants as grotesque, inferior, and naturally suited for slavery. For example, stereotyping Black women as Jezebel — lascivious and oversexed — not only excused white men’s sexual abuse of Black women and girls; the Jezebel stereotype also erased the beauty, attractiveness, and desirability of Black women.

To be sure, white assault on Black beauty was not solely at the philosophical level, far removed from daily life. Slave masters and mistresses routinely shaved the heads of enslaved men, women, and children, and openly expressed revulsion at the sight of Black hair. The formerly enslaved man, James Brittain, recalled to WPA interviewers the routine ways in which masters butchered enslaved people’s hair. Describing his grandmother as having hair that “hung down below her waist,” Brittain described how the wife of his grandmother’s owner, cut her hair as punishment. Whites also ridiculed Blacks for referring to their hair as hair. Wool was the term some whites insisted on labeling Black hair. Remembering the ridicule she faced from her owner, one unnamed enslaved woman recalled,

“Mistress uster ask me what that was I had on my head and I would tell her, ‘hair’, and she said, ‘No, that ain’t hair, that’s wool…my mistress would say, don’t say hair, say wool.”

From nineteenth century children’s books and minstrel shows that ridiculed Black hair as woolly, to the ongoing good hair/bad hair binary that assigns hair with fewer kinks and coils as good hair, the devaluing of Black hair persists. Job advertisements for “attractive” girls with “well-groomed” hair (which often meant straightened) and the rejection of dark skinned girls, whose “bushy and uncontrollable” hair made them eligible for few jobs beyond manual labor in twentieth century Jamaica, further shows that these questions of beauty standard are not vain ones. Beauty ideals are entangled even with the ability to make a living. Like the colonialism and slavery context in which the Black/white and ugly/beautiful binaries were created, racialized beauty ideals are intertwined with the economic and political disfranchisement of Black people.

The ongoing assault on Black hair, in which Black girls are removed from school for wearing braids, for example, makes Bennett’s Afro style a potent and timely challenge to the universalizing of Eurocentric features as standard. Bennett’s style choice also has an affirming power. Although the Clarks’ Doll study is well known, few discuss the fact that it was not all children who saw white dolls as beautiful and Black ones as ugly. Most did–but not all. After hundreds of years of conditioning Black people to internalize that they are ugly, not everyone believed it.

How have Blacks resisted internalizing Eurocentric notions of beauty? Within that past, we also find expressions and affirmation of Black beauty on its own terms. The shaving of enslaved people’s hair as punishment, for example, arose partly because of the importance of hair as an expression of self and identity. So unique were Black hairstyles during slavery that description of hair was primary among the features enslavers listed in advertisements to identify and recapture enslaved people who ran away. Variously described as wearing neatly plaited hair, elaborately shaved and rolled hairstyles, and combinations of long and bushy styles, enslaved people groomed their hair in ways that pleased them. According to one eighteenth century account, Blacks “take great pleasure in having their wooly Hair, cut into Lanes or Walks as the Parterre of a Garden.”

The tightly curled hair of Black people not only made possible the braiding, wrapping, and plaited styles, but also, as captured in the poetry of Cheryl Clark, grooming Black hair was a work of art and a pathway to love and acceptance. Time needed and invested in grooming the hair created space for dialogue, bonding, and intimacy, as stylist and stlyee (sometimes as simple as a parent and child) traded stories and exchanged ideas as they co-designed the hairstyle. “Against the war of the tangles,” Clark reflects of her stylist, she “taught me art, gave me good advice, gave me language, made me love something about myself.”

The work of sociologist George Williams in the 1970s illustrates more explicitly the positive impact of conscious efforts to embrace Black hair and to embrace Black as beautiful. Williams was interested in understanding if and how Black people’s attitude toward their hair and beauty had changed since the Clarks’ research in the 1930s. His study concluded that the Black pride cultural revolution, expressed through such movements as Black Power, Garveyism, and Rastafarianism as well as the work of cultural icons like James Brown and Melba Miller (whose book The Black is Beautiful Beauty Book declared war against straight hair), had revolutionized the perception of Black people around the globe. Black people, young and old, male and female, not only sported natural dos, but more significantly, they embraced Blackness and Black hair as beautiful.

The steady decline in sale of hair relaxers and increased demands for natural hair care products further illustrate that the embrace of Black hair was not simply a trend of the 197os. The proliferation of naturalista websites in the last decade and the wearing of natural hairstyles by Miss Universe and Miss World winners Deshauna Barber, Sanneta Myrie, and Zahra Redwood reveals how Black women have used various platforms to promote their own brand of beauty. Davina Bennett’s style choice, therefore, continues a long legacy of challenging white beauty standard suggest a shift toward showcasing the beauty of Black hair as an emerging norm.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Black hair has unlimited tenacity. I remember

as a child after washing my hair once, how beautiful I thought it was. So shiny and curly.

that I could wear it like that in public. But that was back in the early sixties when we pressed

our hair. By the late sixties when I attended college, I wore an afro so proudly. I had learned “I’m Black and I’m Proud” which transformed my life. From there came extensions in the seventies and I was one of

first sisters to where them so eloquently off

and on into the eighties. This was a particularly

revolutionary time in my life. While the movie

“10” stole the glory for being the reason why I wore them, my mother had to take them out

of her hair to get a job. To wear them was viewed as unprofessional. Eventually they

became accepted, along with braids, twists and cornrows. For the past ten yeats, I now adorn my head with locs,which I absolutely love. But the most amazing growth over the years has been the comments from some whites, i.e.,” Is that your real hair ” to “Can I touch it”.to “Your

hair is beautiful”. Thanks for this chance to express my personal jourmey.

Thank you, Yvette Ellis for sharing your journey. I am inspired by your story.