David Garrow, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Politics of History

On June 4th, teachers and professors from all around the United States met in Louisville, Kentucky to review Advanced Placement (AP) U.S. History exams for thousands of students. Graders must follow AP’s basic rubric and appraise student essays based on the “disciplinary practices and reasoning skills” required for the study of history. The AP evaluation criteria stresses four basic benchmarks: evaluating primary and secondary sources; analyzing claims, evidence, and reasoning within sources; providing historical context that connects with evidence; and producing a claim from multiple knowledge layers to support a thesis. Although hundreds of educators are dedicating a full week to assess how well students satisfied these requirements, historian David Garrow’s recent essay on Martin Luther King Jr. does not hold up to similar scrutiny. Garrow’s recent salacious essay on King violates the primary tenets of historical thinking.

Garrow and others assert that historians must grapple with the implications of a new King painted by FBI documents that allegedly claim King participated in acts of sexual avarice and criminal assault. In AP language, this represents a “historical claim,” an argument constructed from primary and secondary source analysis. Critical examination of these sources derive from careful scrutiny of author, point of view, date, and context. Even a cursory review of these components effectively throws Garrow’s argument into doubt.

All document analysis begins with primary questions. Who is the author, and how should we evaluate their point of view? Garrow seems to acknowledge this tenet in the article and ignore it at the same time. He says the FBI is suspicious, then points to them as a legitimate source. If other scholars followed the same practice, then we’d classify the document below as historically accurate.

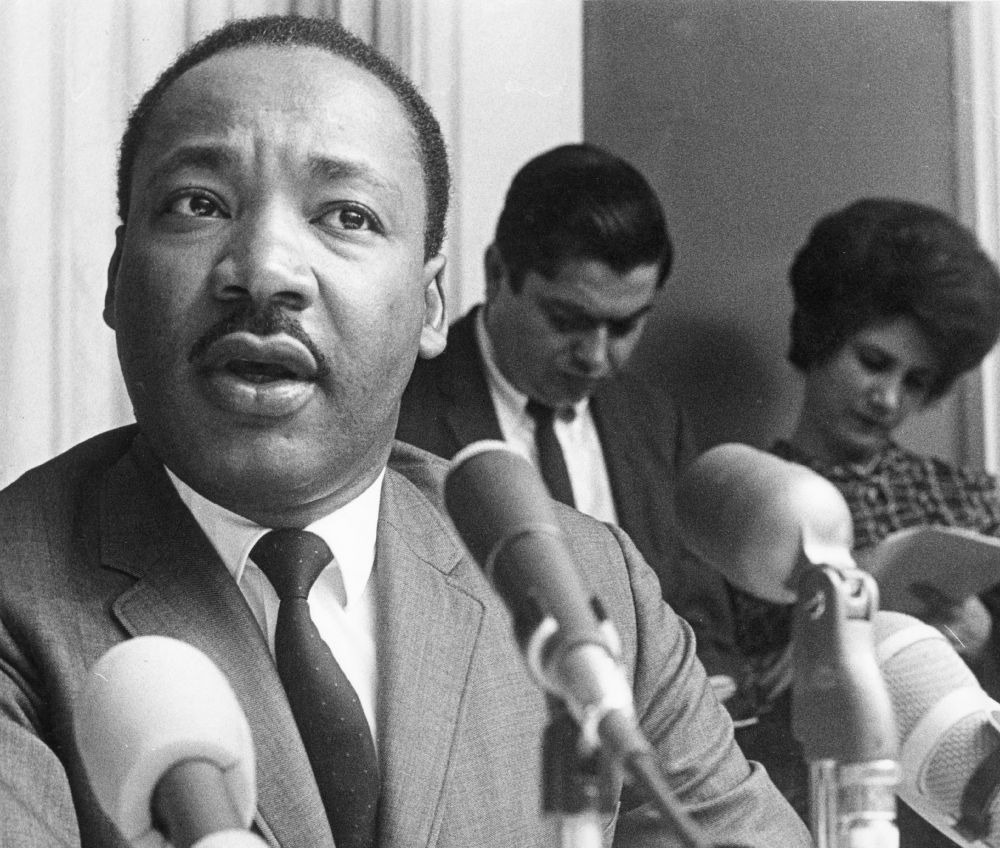

This image was widely distributed by groups like the Ku Klux Klan during the 1960s for the purpose of defaming and vilifying King as a traitor to the United States. However, the picture depicts King at the Highlander School, a training site for nonviolent action. The Klan’s white supremacist ideology is a defining aspect of the author, which leads all readers to severely question the document’s reliability and trustworthiness. Given the incorrect inference, we do not use it as insight into King’s political affiliation, but rather insight into the Klan’s white supremacist motivations.

Here is where Garrow thoroughly misses the mark and fails to wrestle with the source paradox he cites in his own article. The Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) had a bitter impact on groups like the American Indian Movement, Brown Berets, and Black Panther Party (BPP), in addition to targeting non-political organizations like book stores. Public knowledge about the FBI’s role in the assassination of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark is a well-known example of how the FBI utilized threat of jail, harassment, blackmail, and other nefarious methods to gather information and destabilize and destroy Black organizations.

However, one of its key tactics was the dissemination of false documents. As the New York Times pointed out in 1976, “stories were planted with newspaper and television outlets to put the Panthers and their supporters in a bad light.” FBI “reports” went to local police as well to justify trumped up fear and attacks against the BPP. The New York Times piece also noted that false information found its way into other hands which led to “using tax investigations to harass or distract radicals, prejudicing the superiors of college professors and clergymen sympathetic to radical causes and attempts to prevent speeches by radicals.”

COINTELPRO papers outlined specific schematics for how the FBI falsified documents and weaponized these materials against any groups deemed un-American. These papers also clearly delineated fact and fiction, along with the FBI’s intention for destabilization. Garrow references documents that exclude the tactical strategies that typically accompanied such salacious reports, and thus he cannot verify authenticity to create a complete picture. In other words, his interpretation exists in an information vacuum. Professor Michel-Rolph Trouillot argues in Silencing the Past that missing information in document collection can act to skew historical writing. The result is an incomplete and premature picture, that potentially warps historical and material reality.

An additional condition for proficiency in AP U.S. history is the comprehension of an author’s point of view and intent. The FBI point of view characterized King and the whole Black freedom movement as a danger to the United States. The intent of FBI documents was to provide validation for this point of view and a basis for countering the Civil Rights Movement. Why else were they collecting information, if not to execute a plan that demonized King?

Garrow accepts the FBI’s claims but fails to interrogate or question the obvious gaps in source information. This is essential to the historian’s job, but his failure to follow fundamentals opens the door to questions and doubt (like it or not) about Garrow’s own author intent. This query is not a swipe at Garrow alone, it’s a question for every historian. Oral historians like myself and academic scholars like Jennifer Denetdale, Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, and Jeanne Theoharis argue that history writing is an act of power.

As such, what one writes, whose voice comes through, and how the author asserts intent are important philosophies to identify in historical writing. This acknowledgement is a necessity for Garrow given his decision to publish in Standpoint, a conservative British magazine. Even more, it would help readers distinguish between the current Garrow essay and the past Garrow argument in The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr. that, “a healthy skepticism toward what one does find in the files is essential to any intelligent use of the Bureau’s own records.”1

Garrow has bypassed the peer review process to avoid facing academic query and ignored the lessons all young historians must learn. Currently, AP graders are determining if students met the “disciplinary practices and reasoning skills” of good history. Judgement of those who fail to meet the mark is resolute. Accordingly, I grade David Garrow’s essay on King and the FBI as bad gossip history. If historians accept Garrow’s historical claim without question or author explanation, it’s not just a failure of one academic. . . it’s a failure to the field of history.

*Special thanks to GSU lecturer John Frazier for his editorial comments.

- Garrow, David, The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr. (Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England; New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1983):12 ↩