Charles Burnett and the Significance of Black Independent Cinema

When Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight won the best picture Oscar earlier this year, I shared my optimism on this blog about the possible dawning of a new era in Hollywood, one in which the movie industry might finally deal with questions of race on screen with some regularity. Whatever optimism I had quickly receded in light of two of Hollywood’s latest racial controversies—the elision of black women from Sofia Coppola’s update of The Beguiled and the forthcoming HBO show Confederate from Game of Thrones showrunners David Benioff and D.B. Weiss. These recent cinematic offenses were particularly repulsive in light of the racial terrorism in Charlottesville, which was also fueled, in part, by white fantasies of the Confederacy. And this is to say nothing of Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit. This past summer should remind us that the movie industry is entirely inept when it comes to thoughtfully representing the lives of African Americans in particular, and people of color more broadly. Moonlight was not, as I hoped, a genesis but an accident unlikely to repeat itself. In hindsight, there was something Freudian about Faye Dunaway falsely proclaiming La La Land, perhaps the whitest movie of 2016, the winner of Hollywood’s highest honor.

Where, then, are audiences who seek multi-dimensional and complex representations of African Americans to look? Black independent film offers one tonic to Hollywood’s poison. And in light of the recent catastrophic storms in South Texas, Florida, and the Caribbean, one of the most important films within the Black independent film canon is Charles Burnett’s Quiet as Kept (2007), which, in only five minutes, more perceptively examines the complex dynamics of race, the neoliberal state, and capitalism than nearly any Hollywood film of two hours.1 In so doing, Burnett’s film points to a politics of Black independent cinema capable of both addressing the needs of Black communities immobilized by neoliberal policy and contesting the role of Hollywood in that immobilization. It is the latter—Hollywood’s role in the oppression of Black communities in the neoliberal era—that I focus on here.

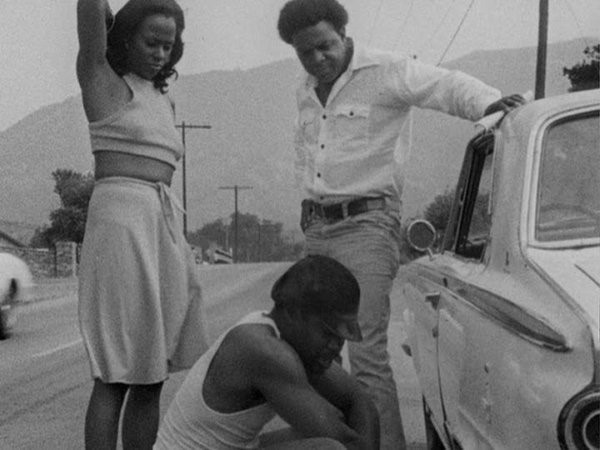

Less than five minutes long, Quiet As Kept has just three characters (The Father, The Mother, and The Son), and consists of hardly more than a single scene. The simple plot centers around a Black family exiled from their home by Hurricane Katrina. Living in temporary housing and relying on FEMA checks, the trio discusses politics, the storm, and Hollywood while The Father attempts to repair the motor of the family car. Near the film’s conclusion, the trio turns to the topic of Hollywood, cataloging and debating representations of Blackness within the industry’s history, and highlighting the sustained inability of the film industry to speak to the needs of Black communities.

Early in the film, The Mother raises the topic of Katrina, which has “showed [her] something about this country.” “People of color and poor folk, we better have a plan B,” she adds. The Son then begs his parents to take him to a movie. Besides being too expensive, “They ain’t no good no more,” his dad replies. The Mother and The Father proceed to argue over what constitutes a “Black” movie and television show. The Father cites “classics” like The Mack and Super Fly with “plenty of Black folks in there.” The Mother prefers The Cosby Show. “That’s like decaffeinated coffee,” jokes The Father. Growing up in the South, there were a multitude of all-Black movies to watch, but Jim Crow laws forced The Father and other African Americans to watch those films from segregated balconies referred to as the “crow’s nest.” Recounting his film-going experiences from his childhood, The Father insists they were a “whole lotta fun if you can get over the lynchings.” Taken together, the Hollywood representations of Blackness listed by The Father and The Mother exemplify the culture industry’s practice of dehumanizing African Americans on screen throughout its history. Moreover, The Father’s remark regarding the constant threat of physical violence that faced Blacks in the Jim Crow South dovetails with the psychological violence of the representations of Blackness both on the movie screens he watched from the crow’s nest and in the visual texts he discusses with his wife.

As with their discussion of the national racial politics revealed by the storm, The Mother concludes her family’s debate about Black images in Hollywood and the film itself with insightful clarity. None of the films and television shows they cite constitute a “Black movie.” “A Black movie” she decides, “would have told us what was going to happen when Katrina hit. It would have told me where I stood in this country. Just like Emmett Till told my father where he stood. . . . I’m serious, and I’m scared.” The inability of movies to speak to the experiences of African Americans highlights the complicity of Hollywood in reproducing racial inequality. Yet, her appeal also emphasizes the possibility of “Black film” to serve as an essential component of larger racial justice struggles. A Black movie, must, in The Mother’s view, do what no Hollywood representation of Black people has done, or is likely capable of doing.

For Burnett, Black independent filmmakers must make films that reveal the machinations of white supremacy in our current historical moment, just as Emmett Till revealed the racial terror of Jim Crow. Quiet as Kept, in this sense, points toward a blueprint for Black independent filmmakers. In this short film, Burnett yokes the dehumanizing representations of Blacks in film and television, to the social, political, and economic oppression of African Americans in the neoliberal era. When The Father asks his wife, “Why you gonna blame all our problems on a little ass movie,” The Mother responds that it is because those displaced by the storm cannot go home; they do not have the resources or the government support to do so. And it is precisely because the representations of Blackness have so fundamentally impacted Black people’s lived experiences of racism that The Mother can hold Hollywood accountable.

That Burnett’s work proved so perceptive, despite its length, is unsurprising. The filmmaker was part of the acclaimed “LA Rebellion”—a collection of Black independent filmmakers trained at UCLA in the 1970s that included Haile Gerima and Julie Dash—who were, as Burnett once put it, “concern[ed] about the images that were perpetuated by Hollywood movies . . .” Members of the Rebellion sought to make films that “corrected” Hollywood representations of Blackness and spoke to the needs of the Black communities in which they lived. Beginning with Killer of Sheep (1978), a film Burnett once described as “totally anti-Hollywood,” Burnett’s films offer, according to one scholar, “rich characterizations, morally and emotionally complex narratives, and intricately observed tales of African American life.”

When asked directly about the role of Black independent filmmakers in solving the problems facing Black communities, Burnett responded, “Self-esteem has to be rebuilt. . . . Commercial movies are escapist. Not everybody has fantasies about judo-chopping someone to death. We need stories dealing with emotions, with real problems like growing up and coming to grips with who you are; movies that give you a sense of direction, an example.” After ruling out a movie, and after The Father warns of their forthcoming eviction because of his family’s inability to pay rent, The Mother suggests a stroll around their block. An absurd idea, The Father snaps back, “this is drive-by shooting country.” The film ends where it begins; the family car is still inoperable, The Son still bored, the family still stuck. All this family can do is wait–wait for a more racially just and democratic country, and wait for, in Burnett’s eyes, a politics of Black independent film that can help them get moving.

Hurricane Katrina showed us that race will not only shape our public debates about who is and who is not “deserving” of our sympathy but it will also be a determining factor in our priorities regarding evacuation, the allocation of relief aid, and rebuilding efforts. We are, in fact, already seeing this in the Caribbean in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma. As rebuilding efforts begin, Black communities will likely bear a disproportionate burden of the ongoing suffering caused by recent catastrophic storms. I fear that the months ahead will again painfully remind us of how little value we place on Black lives. That will leave many of us returning to questions about how white supremacy continues to make and remake itself in our current historical moment. To that end, it is imperative that we hold Hollywood accountable for its ongoing role in devaluing Black life, and support independent Black films that seek to support Black communities and provide multi-dimensional and nuanced representations of African Americans.

- This post draws on my recent article, “They Should Have Called Katrina ‘Gone with the Wind’: Charles Burnett’s Quiet As Kept and the Neoliberal Racial State.” in Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture and Society, Vol. 19, No. 2 (April-June 2017): 162-176. ↩