The Politics of Black Cinematic Representation

A recent article on Detroit described the film as “the most irresponsible and dangerous movie of the year.” The authors highlight Kathryn Bigelow’s directing choices about what to include and what to omit in recreating the 1967 uprising, and conclude that the film ultimately leaves viewers with one-dimensional characters and little to no context on systemic racism and political engagement in the city of Detroit. Other viewers have decried the film’s erasure of Black women supposedly for historical accuracy. Similar critiques have been leveled at HBO’s proposed forthcoming series Confederate. Here too, commentators have expressed many reservations, including skepticism about a show that is premised on casting the racist legacy of slavery as a fictive alternative world, rather than as the ever-present reality that it is for some.

As the critics of Detroit and Confederate show, the stakes of historical representation are high, perhaps even more so when those histories require us to grapple with the enduring realities of racism. These critiques are yet another reminder that representing Black lives on screen is not simply a question of increasing the number of productions with Black actors. It is also a question of how these stories are told. They ask us to consider what is emphasized and what is excluded? What are the implications of telling a story this way or that? Of telling a story at all?

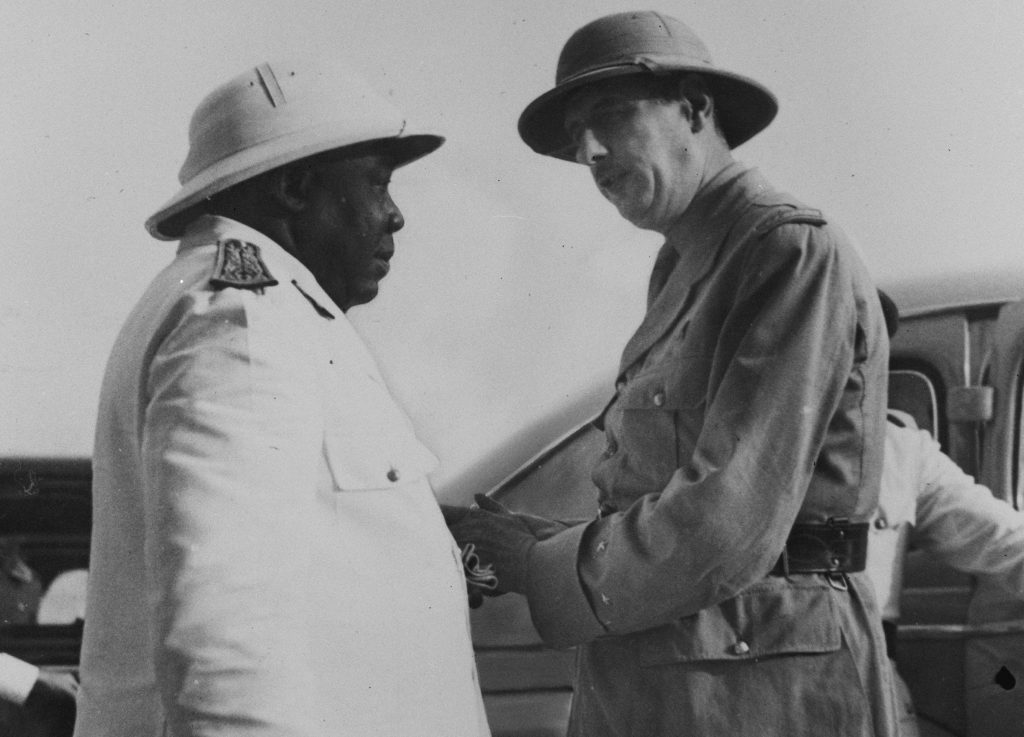

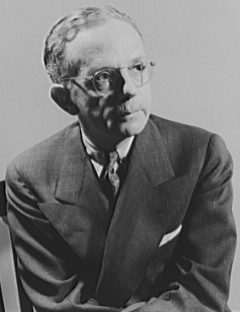

In 1943, as World War II raged on, a civil rights activist and a Hollywood producer tried to answer these questions. For three months, Walter White, who served as executive secretary of the NAACP for over twenty years, and Walter Wanger, then a semi-independent producer affiliated with Universal Studios, exchanged letters discussing White’s proposal to make a film about the colonial administrator Félix Éboué and his contributions to the war effort. Éboué was born in French Guiana and educated in France. He went on to become a high ranking colonial administrator, serving in Martinique, Guadeloupe, and French Equatorial Africa. He was governor of Chad in 1940 when France was invaded by Nazi Germany. Today, history remembers Éboué as the first French administrator to rally troops for Charles de Gaulle’s nascent Free France movement. At a time when France was militarily weakened and under the rule of a Nazi collaborationist regime, the colonial troops and resources that Éboué organized, turned the tide of the war.

Walter White met and interviewed Éboué in Cairo barely a month before the latter’s death. On his passing, he received France’s highest posthumous honor by becoming the first Black person to be buried in the Pantheon. Éboué is an important historical figure whose life and work remain understudied. White believed this as early as 1943 when he petitioned President Roosevelt to invite Éboué to the White House and pitched his biopic to the Office of War Information and his contacts in Hollywood. The correspondence between White and Wanger sheds useful light on the historical dimensions of the on-going debate on how to represent Black lives on the big screen.

How should Hollywood represent the everyday lives of Black people and the roles of prominent figures like Éboué? White believed first and foremost in making a film backed by rigorous historical documentation. He sent Wanger several letters and articles about Éboué, as well as copies of the French administrator’s speeches. He also provided addresses to archives and the French Resistance movement’s library in New York City, and offered his and his colleagues’ services in conducting research at these sites for the film project. White believed that a robust knowledge of history would allow Hollywood to recognize the important contributions that Black people were making to world history. He hoped that this recognition would in turn open the way for an increased diversity of roles and end the typecasting of Black actors boxed into stereotypical roles. Interestingly, opposition to White came from Black actors who feared that eliminating these roles would leave them without jobs.

White anticipated the objections of Hollywood executives who, even today, couch their resistance to films with a Black lead or a predominantly Black cast in terms of revenue: “Ninety percent of the theatre goers of the United States are white. Unless an all-Negro film has some unusual value or distinction, white people are not going to see it except as a curiosity. I feel that the failure of the films to make money, or perhaps even lose money, might cause some of the producers to decide against making any more entirely Negro pictures […]. I am trying to be as realistic as possible.” White also tried to forestall the backlash that likely awaited a film aiming to rewrite the narrative on World War II to center a Black protagonist, a man who the Chicago Defender would later describe in a 1949 headline as “the Negro who defeated Hitler.” He pleaded with Wanger to take seriously his vision of a film that would appeal to all, including white southerners: “such a film could treat Éboué as a great administrator who incidentally happens to be a Negro and whose ability and courage played a role which may be decisive in the winning of the war. The fact that he is a ‘foreign’ Negro instead of an American one would lessen any objections to southern distribution.”

There is no doubt that White was deeply invested in promoting new narratives of Black political actors. Yet he also felt it necessary to underplay Éboué’s race and disassociate him from Blackness in a U.S. context in order to make the film more palatable to a white American audience. He believed that this compromise would be in the service of “the much bigger objective […] namely, picturization of the Negro as a normal and integral part of the life of America and the world. A picture about Éboué showing the part that he played not solely among the people of French Equatorial Africa who are Black, but among the peoples of the world whose fate may be determined by the turn of the war in North Africa, will do more good than a thousand ‘Cabin in the Sky’s’ or ‘Porgy and Bess’s.” In his critique of two of the major all-Black productions at the time, White suggests, problematically, that a film marketed for a primarily Black audience would render their stories illegible to white viewers and impede his larger goal of showing Black people as protagonists in both everyday life in the United States and in the unfolding political developments of a historical moment as crucial as World War II.

Wanger ultimately turned down the Éboué project for Universal Studios, but the reason he gave was neither financial nor a fear of white southerners’ uproar. His initial enthusiastic reception of White’s proposal gave way to a sudden terse rejection “not because of the colored question but because of our relations with the French.” If there was one objection that White had not anticipated, it was Wanger’s suggestion that racial tensions in France and not the United States made a Black World War II hero impossible. For Wanger, making a film about Éboué would be a political act, one with negative consequences for American foreign relations, particularly with allies. Both men inadvertently agreed on one crucial point, that the stakes of remembering and recognizing Black lives were high.

Three years after White’s project fell apart, Eslanda Robeson would take up the mantle of producing a film about Éboué for an American audience. She wrote to Félix’s wife, Eugénie, informing her of her impending trip to Central Africa where she would retrace Éboué’s steps and write a script about his life and work. Paul Robeson was to play Félix Éboué. This film too was never made.

Anne McClintock writes that “history is a series of social fabulations that we cannot do without. It is an inventive practice, but not just any invention will do. For it is the future, not the past, that is at stake in the contest over which memories survive.” This contest over the survival of memories was at the heart of White’s vision for commemorating Éboué’s life and work on screen. It has remained at the forefront of public debates in recent months about productions like Detroit, Confederate, and others, that contribute, for better or for worse, to present, urgent conversations about Black lives in America. Hollywood’s historical representations are one of the myriad inventive practices that make history a very real and pertinent presence, one that is as much about imagining the future as it is about remembering the past.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Gorgeous article. Thank you for such an accessible, useful text.

Kerry

Thank you Kerry! I am glad you found it useful.