Centering the Voices of Black Activists in Post-Revolutionary Cuba

This post is part of our online roundtable on Devyn Spence Benson’s Antiracism in Cuba.

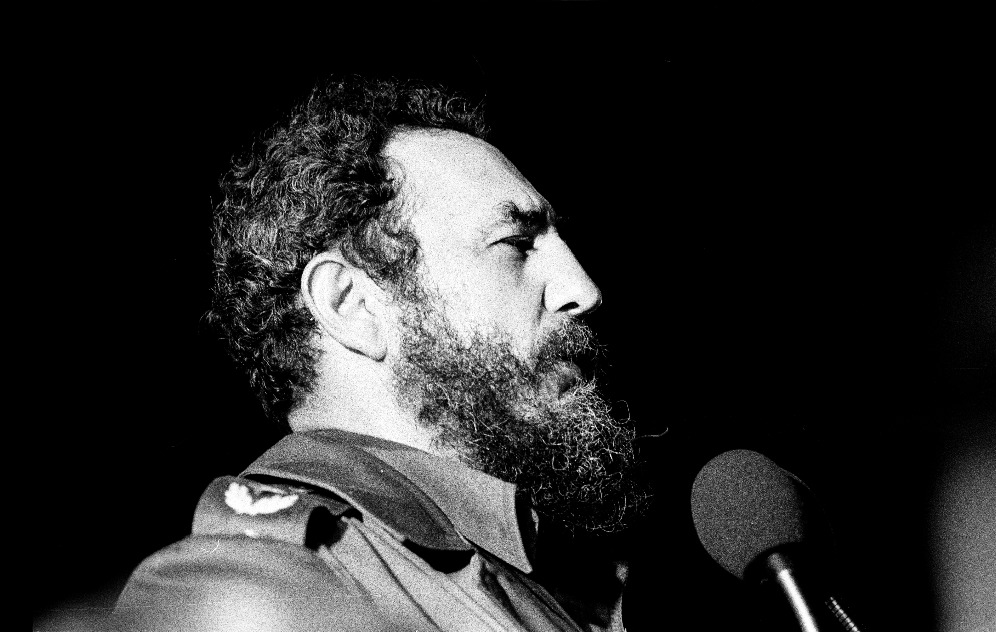

There are few in the United States who on hearing the word “Cuba” do not immediately picture young fatigue-clad guerrillas high in the island’s majestic Sierra Maestra mountain range, marching single-file along a path cleared by their arms as they push away dense tropical foliage. Fidel Castro, arguably the most iconic figure of twentieth-century revolutions, often comes to mind as well: the bearded rebel leader and revolutionary man of the people who erected a socialist bastion in the United States’ own backyard. Cuba’s David to our North American Goliath.

A much smaller group of US leftists, rightists, journalists, academic researchers, and well-informed laypersons knows that after Cuban and United States diplomatic ties and economic investments were severed in the Revolution’s early years, the moral legitimacy and economic efficacy of Cuba’s socialist system—understood as diametrically opposed to the ideals and goals of capitalism in the US—were judged by a self-serving standard. That is, the successes and failures of the Revolution’s healthcare, education and literacy, transportation, social equity, conservation, pharmaceuticals, and housing programs have been commandeered by both Right and Left to explain an inexorably bifurcated world order.

Fewer still are aware that historically, since the early twentieth century, in Cuba and the United States the comparative socioeconomic status of the African descended often has serviced this raging ideological war over which nation better respects humanity and has the greatest potential to ensure human rights, dignity, and social equality for all citizens. Historian Devyn Spence Benson weaves her way through this minefield of appropriated racial meanings, strategies, and exclusions in her carefully researched book, Antiracism in Cuba: The Unfinished Revolution.

This book, which focuses on post-revolutionary Cuba’s campaign to end discrimination, is among very few book-length studies that probe the logics of Black Cubans’ socioeconomic status, the humanity (or lack thereof) accorded them, their strategies to mitigate racial inequality, and the meaning assigned to blackness in Cuba after 1959. In doing so, Benson’s book makes an excellent contribution to ongoing scholarly debates on racism, nationalism, and anti-racist movements in modern times—debates that often are clustered around Cuba’s late nineteenth and early twentieth-century period and even draw wholesale on the Revolution’s promise of social justice. She recovers Blacks’ ongoing struggle for full citizenship as well as the historical meaning of blackness in the latter half of twentieth-century Cuba. Though spatial limitations preclude a full discussion here of this rich work, I will point to some of its many strengths and strong contributions toward a more nuanced, theoretically engaged narrative of Cuba’s racial past.

Armed with extensive archival documents, printed primary-source periodicals, oral interviews, and personal papers, Benson lends a refreshingly sophisticated approach to the study of race and revolution. One central concern is tracing the social hierarchies and entrenched racism of prerevolutionary Cuba that survived after 1959, despite a vociferously proclaimed revolutionary social justice agenda. As Benson convincingly shows, officials juxtaposed Cuba’s egalitarian agenda to the pervasive in humanity and anti-Black racism of North America. For example, Fidel issued a 1960 invitation to North Americans (especially Blacks) to visit Cuba and experience the “full citizenship,” that was, he suggested, unattainable in the US. Further, she documents young Cuban anti-imperialist protesters who denounced KKK activism in the US, suggesting that there “demokkkracy” was a hypocricy. She also reminds the reader that in 1960, Cuban protesters responded to the violence perpetrated against young Civil Rights activists who had sat in at a Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. Cubans picketed downtown Havana’s Woolworth, in solidarity, carrying signs that read, “Woolworth Denies Rights to Blacks.”

Benson’s clear definitions of forms of Black Cuban activism, such as “integrationist” or “negrista” (racial consciousness) help readers unfamiliar with social contexts outside the United States. She uses these concepts to frame a larger discussion of how, when, and if government officials interpreted integrationist organizations and negrista public intellectuals (such as Walterio Carbonell and Juan René Betancourt) as opposed to the Revolution. Here is where Benson demonstrates her even-handed treatment of the Revolution’s paradoxes and evokes empathy in the reader for all historical actors: Black Cuban activists, revolutionary concerns over social justice as well as the government’s ineffectual, politic nods to racial justice.

Another of the book’s strengths is its century-long historicization of Cuban tropes of blackness–from nineteenth-century anticolonial social discourses to the mid-twentieth century as social relations were recast in the image of revolution. For much of this period, Blacks were integral to the concept of a multi-racial Cuban national community—their presence was central to support a nationalist narrative of egalitarian inclusion, despite their daily experiences with inequality. As historian Ada Ferrer has argued, during colonialism the imagined Cuban national community included Black people, yet rejected as unpatriotic their demands for the rights of full citizenship. Benson shows that revolutionary doctrine notwithstanding, Black Cubans experienced similar marginalization after 1959. In fact, in both historical contexts, asserting Black consciousness and/or demanding Black empowerment often were equated with the nation’s undoing.

The 1961 Literacy Campaign (Campaña Nacional de Alfabetización) is a worthy touchstone of the author’s argument. The campaign to end illiteracy mobilized an estimated 142,000 Cuban “teachers” across the island. The Brigadistas–as these teachers, students, and volunteers were known–traveled to rural and depressed areas of the island to provide literacy instruction to more than 700,000 people. They improved the national literacy rate, raising it from 60 to 73 percent to a whopping 96 percent by the campaign’s end. Benson argues that Fidel Castro and others suggested that because large numbers of Blacks benefited from the campaign, the Revolution had dealt a blow to Cuban racism. That is, officials argued that rather than advocate for Black rights, Cuba’s socialist revolution would end discrimination by providing equal economic and employment opportunities to all.

Benson bolsters her discussion when she unpacks revolutionary constructions of blackness following the murder of Literacy Campaign teacher Conrado Benítez by CIA-sponsored counterrevolutionaries. She posits that news of his violent death was co-opted by officials as a metaphor North American aggression leveled against the Cuban national family. Further, as Benson suggests, officials pledged that anti-Black violence would be curtailed by the strength of Cuba’s raceless nation unified against external capitalist interests, rather than via Black activism. Indeed, just as the grateful, subservient Black, nationalist patriot was popularly idealized during the nineteenth-century anticolonial wars, in death the young Benítez is martyred first and foremost on behalf of the nation. As were other twentieth-century Black activists publicly lauded for their service to the national community, honor stemmed from his selfless service to the Cuban Revolution.

The author also successfully probes the relationship between Black activism and the social policies adopted by the Revolution. Using a multi-layered analytical framework, Benson shows that it is possible to generate a nuanced set of arguments about racial politics in Cuba and abroad. She recounts strategies deployed by the Revolution to both delegitimize Washington and capitalism and buttress its own claim to popular representation of women, workers, youth, and Blacks in nationalist development. In fact, when I cracked the spine on this brave study I immediately understood that the book’s central concern is to recover the experiences and narratives of the African descended, allowing them to drive the story line.

Returning to the opening of my commentary, Black detractors of the Revolution (usually expats or self-exiled Cubans living abroad, such as Carlos Moore) claim that the island’s socialist regime has denied rather than supported Blacks’ struggles for socioeconomic justice. They suggest that more than gains for Blacks Cuba has been a country of repression, government-sponsored racism, and socioeconomic inequality. By extension, they suggest, leftist movements everywhere threaten Black economic stability as well as human rights. The author balances so polarizing a narrative by calling to our attention that even as Cuban officials signaled to Jim Crow segregation and anti-Black violence to propagandize Cuban socialism, Black Cubans as a whole did experience tangible change in healthcare benefits, education, professional opportunities, and access to the public spaces (parks, restaurants, businesses, etc.) that were segregated before 1959. The Revolution, in other words, has shown support for Black people and all vulnerable populations in Cuba and has practiced government policies that run in stark contrast to the abuses of capitalism.

Ultimately, this highly recommended book commits fully to Black Cubans’ consciousness, activism, and socioeconomic status. Devyn Spence Benson’s well-conceived arguments and fascinating stories enable scholars and laypersons alike to better understand how and why exploiting Black activism and experiences for ideological purposes in Cuba, the United States, or anywhere runs counter to human rights and mitigates the strength of social justice work, including anti-racist campaigns.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Your review of “Antiracism In Cuba “, really stimulated my interest to read the book. I placed an order on Amazon and should have it in my hands in two days. Thank you for your review.

Also, I am seeking a starting point for the historical relationship between Dominican Republic and Hati. I would appreciate any book referrals you may have.