Black Power’s Global Pulse

This year, the Black Panther Party (BPP), arguably the most influential Black Power organization, celebrated fifty years since its founding. While many remember the Party for its political influence in the United States, the BPP was also one of the key Black Power organizations in the world. The Party’s global reach underscores how Black Power has always been an international phenomenon. Indeed, the movement’s global experience cannot be pressed into the bars, boundaries, and barrios of the United States.

The Black Power Movement laid its first tracks in “Africa-America.” In 1966, Kwame Ture made a call for Black Power in the summer heat of Greenwood, Mississippi. He was not the first to do so. In the nineteenth century Edward Blyden charged that blacks needed “some African power.” Richard Wright’s Black Power—based on his trip to the Gold Coast—was published in 1954. Just months before Mukasa Dada urged Ture to speak on it, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. referenced Black Power during a speech at Howard University. Yet, it was the uttering of the Trinidad-born chairperson of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) that triggered a new political movement.

Black Power loved black people. Globally speaking, the Movement produced far more than spontaneous covers of its American mainland expressions. At its apex, it had the potential to shake the world off of its mythical spindle of white supremacy. In addition to the organic influences of the African-American freedom struggle, Black Power’s global versions were very much impacted by local, (trans)national, regional, and international factors. Across the world, Black Power instrumentally called for the overthrow of white hegemony’s manifestations—racism, (neo)colonialism, class oppression, white violence, capitalism, sexism, and imperialism.

Originating as a rallying cry for black youth across the United States, Black Power rapidly developed into a global anti-colonial movement. It trod across the world in ways both predictable and unexpected, weaving through a labyrinth of ironic possibilities. Through a myriad of twists and turns, it linked the black world through intentionality, coincidence, and sometimes contradiction. Driven by aims both concrete and uncertain, it traversed the historic webs of black internationalism. From the gravel of these well-traveled roads of black protest, it paved new routes of Diasporic radicalism.

Black Power was a time-traveling sound system

Black Power pressed the button. It juggled vintage tunes from the deep crates of the Black Radical Tradition—African rebellions against slavery, cimarronaje, pan-Africanism, Black Nationalism, Negritude, liberation theology, the Communist International, Afro-Asian revolutionary praxis, Black women’s internationalism, Civil Rights and Black Arts movements, and Caribbean and Africana liberation struggles. Its dub plates carried the names of Nzinga Mbande, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Antigua’s Aba, José Leonardo Chirino, Guyana’s Cuffy, Harriet Tubman, Bussa of Barbados, Nat Turner, Sally Bassett, Frederick Douglass, François Mackandal, Queen Nanny, Zumbi dos Palmares, Gaspar Yanga, Paul Bogle, Claudia Jones, Marcus and Amy Jacques Garvey, Mãe Menininha, George Padmore, Amy Ashwood, W.E.B. Dubois, Queen Mother Moore, Malcolm X, Jeanne and Paulette Nardal, Aimé and Suzanne Césaire, Kwame Nkrumah, Yuri Kochiyama, Fidel Castro, Ella Baker, Peter Tosh, Nina Simone, Claude McKay, Kwame Ture, Miriam Makeba, Australia’s Pemulwuy, Fela Kuti, John Kasaipwalova, Louise Bennett, Frantz Fanon, James Baldwin, Tasmania’s Truganini, Amiri Baraka, Déwé Gorodé, Che Guevara, Will `Ilolahia, Haile Selassie, Walter Lini, Bobbi Sykes, Bhimrao Ambedkar, Chief Ataï, Angela Davis, and Muhammad Ali. It was untouchable. Black and brown communities across the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans ingeniously sampled the sounds and symbols of Black Power. They remixed these international lyrics of liberation into the rhythms of their regional struggles for self-determination.

Black Power was loud, but not bombastic. It sounded off “mic checks” in the groundings of the ghettos, the radios, los estadios olímpicos, the dojos, the favelas, the houses of the poor, the shanty towns, the maroon towns, the back-a-towns, the swamps and the cotton fields, the binghis, the high schools, the zinc fences, the tenements, the nakamals, the villages, the corroborees, the college yards, the dancehalls, the pews, the temples, the masjeds, and the gazas. Black Power was born pon the gully side—it did not choose to be. Sometimes it scratched its own records and played the wrong mixes. It simultaneously frightened and befriended many whites.

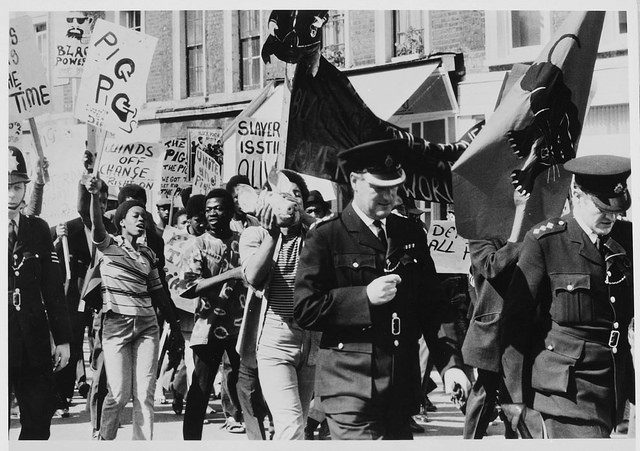

Black Power mixed what it liked. With its speakers turned all the way up, its rebel music overturned the tables of police commissioners and stiff-necked governors—her majesty’s boys sent from overseas to silence the Movement. As they listened over their radios, Black Power split the ears of their foot soldiers—their informers, agents, overseers, sentinels, Tonton Macoutes, Special Branch, spooks who sat by the door, 007s, X-9s, one time, 12, 5-0, Babylon, Babylon boops, Bobby sucks, Bobby wrong, boy blue, soup, po-po, po-lice men, policías, plain clothes, narcos, cowboys, cadets, korps, kiaps, askaris, zombies, “look out fetishes,” gendarmers, tàkk-der, butina preta, black and blue, news carrying dreads, bug-a-wires, rasta impostas, pigs, pandas, ghetto birds, paddy wagons, rollers and patrollers, squaddies, black Marias, Captain Americas and Sheriff John Browns.

The records that these provocateurs left behind speak volumes about the wars waged against the women and men of Black Power. State forces mercilessly attacked the Movement through a number of channels—intense surveillance, political persecution, immigration controls, violence, and propaganda. Albums of martyrs, fallen soldiers, bruises, cuts and scars, political prisoners, and neo-colonies have been left behind in the wake of these assaults. Painful memories. Wounded children of the revolution: we hear and see you.

But some records must be played on both sides, at forty-five revolutions per martyr. Black Power refused to be penned in the inglorious spots—it raised arms, assassinated governors and their hungry dogs, escaped its incarcerated comrades, obtained political asylums, and chased away baldheads. Battles were lost and won. Some freed themselves, while others continue to hum from within their iron cages. Black Power never licked marbles with John Crow, for there is no killing what cannot be killed.

Is there a connection between Geronimo Pratt, Christopher Dorner, Micah Xavier Johnson, Gavin Long, and Marx Essex? If Julius Lester used his Revolutionary Notes to compose the score, the answer might be that the oppressed will continue to be massacred at leisure until they learn to ginga in the only music that their predator understands—“the sound of gunfire, the sound of dynamite, the sound of his death in his own ear.”

As long as white power possesses a heartbeat—Amadou Diallo, Sandra Bland, Erskine “Buck” Burrows, Julieka Dhu, Steve Biko, Yvette Smith, Alton Sterling, Melissa Dunn, Kendra James, Mulrunji Doomadgee, Trayvon Martin, Natasha McKenna, Mike Brown, Philando Castile et. al.—chants for Black Power will be heard. Add this chorus for liberation from the never-ending roll call.

Quito J. Swan is an Associate Professor of African Diaspora history at Howard University and author of Black Power in Bermuda: The Struggle For Decolonization. His next book project is entitled Melanesia’s Way: Black Internationalism in the South Pacific. Follow him on Twitter @QuitoSwan.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Great article