Birmingham in Five Acts

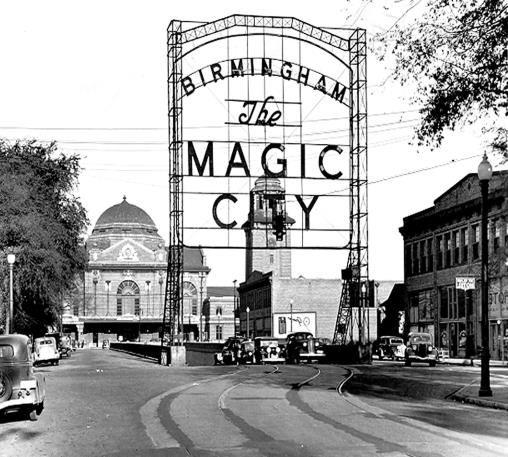

Beginnings

John T. Milner had big goals for a new railroad connecting north and south Alabama. The man just named chief engineer on the Alabama Central Railroad thought that it would come to rival the Western & Atlantic Railroad running through his native Georgia. In fact, Milner believed that the Alabama Central would not only spur the development of the state but also make it the leading supplier of coal and iron to the rest of the Americas.

The outbreak of the Civil War would put a brief hitch in Milner’s plans. But, during Reconstruction, he resumed work on the new railroad. Now called the South & North Railroad, it crossed the path of the Alabama & Chattanooga Railroad, which ran from east Tennessee before descending from northern Alabama into southern Mississippi. A new industrial city would grow at their intersection. It was called Birmingham.

Jim Crow

Milner was now a state senator. He was an author, too. As white politicians in neighboring Mississippi devised a plan for black disfranchisement, he published White Men of Alabama Stand Together. The tract had an argument as blunt as the title. In it, Milner insisted that blacks were “the lowest and most degraded of all races of men, but the most docile and easily controlled.” In fact, Milner continued, “history shows that the African has produced nothing worthy of record except the results of his labor in a material way as a slave on the Continent of America under the guidance of the white man.”1

Not long after Milner called for the continued re-enslavement of African Americans, the sheriff of Shelby County, Alabama arrested Green Cottenham for vagrancy. The twenty-two year old son of former slaves was guilty of no crime. No matter. Cottenham was quickly convicted and sentenced to thirty-days of hard labor. The sentence became a year. Cottenham toiled in the Pratt Mines, a vast mining system owned by a subsidiary of U.S. Steel located on the outskirts of Birmingham. In the mines, Cottenham was subject to the whip and infectious disease. He died from the latter—tuberculosis—within four months.2

World War II

The United States was at war and Milner was long dead. But the legacy of a man eulogized by the New York Times as “the most conspicuous figure in the creation of Alabama, and one of the ablest and most distinguished citizens of Alabama” was very much alive.3 It was to Viola Cosley. The Birmingham resident wrote to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt during the 1940s. “I am a colored mother and need you’r help,” she began, her

boy answered an advertisement in our Post paper for a job as he was out of work and had myself and two younger boys depending on him. As it turned our they were sent to Clewiston, Fla. a month ago and he cant get away or write I am worried about him as Ive talked to some white people and told them just how they are being treated guarded al night by armed guards and not allowed to write home. Won’t you please help me get my son home. And please dont send this letter back because I am afraid if they find out Ive written to you they will kill my boy.

Her child’s name was Marion Henry Cosley. The U.S. Sugar Corporation had him and would not let him go. It was like he was in “a Nazi camp of some kind.”4

The 60s

Five little girls chatted in the bathroom of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. School had just begun. It was Youth Day at their church. The day—the moment—was full of promise. And then the bomb exploded. Four of the girls lay dead, one forever blinded. A day later, white attorney Charles Morgan spoke before the Birmingham Young Men’s Business Club. He told them that yesterday

while Birmingham, which prides itself on the number of its churches, was attending worship services, a bomb went off and an all-white police force moved into action, a police force which has been praised by city officials and others at least once a day for a month or so. A police force which has solved no bombings. A police force which many Negroes feel is perpetrating the very evils we decry. And why would Negroes think this?

“What’s it like living in Birmingham,” he asked. “No one ever really has known and no one will until this city becomes part of the United States.” It was not long before white supremacists drove the traitor Charles Morgan out of town.

Today

My run takes me down Richard Arrington Boulevard, past the Jefferson County Courthouse, and down 9th Avenue North. It takes me past the Birmingham-Jefferson Convention Complex. I remember that participants at a recent Trump rally held at that venue beat up a black man while calling him “nigger.” I speed up.

I continue down 9th Avenue North before turning into Oak Hill Cemetery. I veer up the steep path, my breath becoming short. Finally, I reach the grave of Fred Shuttlesworth.

Just before his death, Shuttlesworth returned to the city he transformed. The co-founding minister of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference died still bearing the scars from Bull Connor’s fire hoses. And so I pause. Out of reverence, out of respect. Out of necessity.

I look out from his grave onto the city of Birmingham. I see a city targeted by the National Bar Association for its record of police brutality. I see the largest city in a state with the fourth highest incarceration rate in the country and its most overcrowded prisons. I see the most populated city in a county that suspends one quarter of its students every year.

I can’t stop. I start running again, picking up pace as I turn out of the cemetery. I head back up 9th Avenue North strengthened, knowing that Shuttlesworth walked through this same path in the once and present city of John T. Milner.

- John T. Milner, White Men of Alabama Stand Together, 1860 and 1890 (Birmingham: McDavid Printing Company, 1890), 9. ↩

- On Cottenham, see Douglas Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Doubleday, 2008). ↩

- “Death of Col. John T. Milner,” New York Times, August 19, 1898. ↩

- Risa L. Goluboff, “’Won’t You Please Help Me Get My Son Home’: Peonage, Patronage, and Protest in the World War II Urban South,” Law & Social Inquiry 24, no. 4 (Autumn 1999): 786-787. ↩