Pivoting Between Black Power and Women’s Liberation

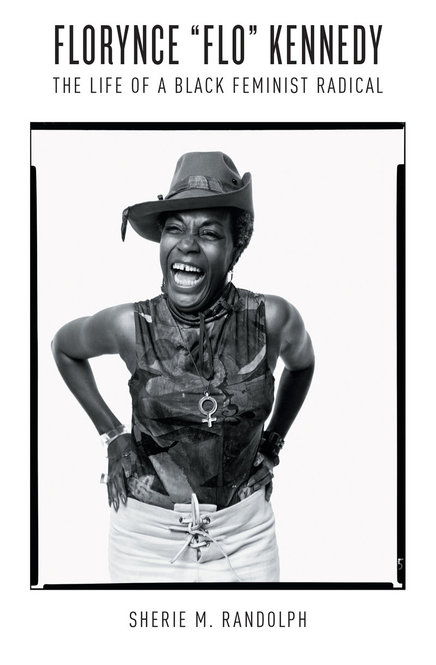

Review: Sherie M. Randolph, Florynce “Flo” Kennedy: The Life of a Black Feminist Radical (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015)

Sherie M. Randolph’s Florynce “Flo” Kennedy: The Life of a Black Feminist Radical is not simply a stunning portrait of one indefatigable black woman. It is also a deeply researched and careful study of the pivotal position that black feminists and black feminist politics occupied in the formation of radical liberation movements in the three decades following World War II. In addition to manuscript collections housed in the usual archives (Schomburg Center, Tamiment Library, FBI files, Library of Congress, etc.), Randolph went above and beyond this traditional source base and acquired access to Kennedy’s personal papers, which at the time of her research were in the possession of Kennedy’s sister. This trove of Kennedy’s papers, spread over cigarette packs, meeting minutes, telephone bills, posters, political buttons, and other forms of paper, form an uneven and unconventional archive, and Randolph convincingly puts the pieces together and transforms this archive of ephemera into an ordered collection. Indeed, cataloging and depositing Kennedy’s papers with the Schlesinger library in Cambridge, Massachusetts is part of the labor that comprises Randolph’s work on Flo’s life.

Sherie M. Randolph’s Florynce “Flo” Kennedy: The Life of a Black Feminist Radical is not simply a stunning portrait of one indefatigable black woman. It is also a deeply researched and careful study of the pivotal position that black feminists and black feminist politics occupied in the formation of radical liberation movements in the three decades following World War II. In addition to manuscript collections housed in the usual archives (Schomburg Center, Tamiment Library, FBI files, Library of Congress, etc.), Randolph went above and beyond this traditional source base and acquired access to Kennedy’s personal papers, which at the time of her research were in the possession of Kennedy’s sister. This trove of Kennedy’s papers, spread over cigarette packs, meeting minutes, telephone bills, posters, political buttons, and other forms of paper, form an uneven and unconventional archive, and Randolph convincingly puts the pieces together and transforms this archive of ephemera into an ordered collection. Indeed, cataloging and depositing Kennedy’s papers with the Schlesinger library in Cambridge, Massachusetts is part of the labor that comprises Randolph’s work on Flo’s life.

Working to unsettle the over-generalized assumption that mainstream, predominantly white-led women’s liberation movements had little contact and experience with “alternative views that centered on ending racism along with sexism,” Randolph presents a more than compelling case that, through their encounters and engagements with Florynce “Flo” Kennedy, mainstream bodies such as the National Organization of Women (NOW) were more than sufficiently exposed to radical alternatives. In fact certain women in these organizations learned from and were coached by Kennedy on how to build coalitions with other oppressed minorities. Indeed, as Randolph makes abundantly clear, Kennedy willingly and forcefully asserted her position as a bridge between various strands and iterations of Black Power, anti-war movements, and Women’s Liberation.

Chapter one of Randolph’s study begins with Kennedy’s childhood, growing up in a lower middle-class home in a predominantly white neighborhood in Kansas City during segregation. One of the first things we learn about Kennedy in this context is that her home life was one where premarital sex, “Not taking shit” from whites, and women’s independence were encouraged and valued orientations. From an early age, then, Kennedy was provided with an implicit sense of how black liberation and women’s liberation both worked in tandem and in tension with one another. Yet she was also learning from an early age to radically question “respectability” politics, and by extension her family life provides us with a stark reminder that not all middle-class or upwardly mobile black women embraced respectability. Thus we see an aspect of Kennedy that Randolph continually highlights throughout the text: how Kennedy’s life trajectory should urge us to think twice about commonly reiterated narratives regarding black politics of the post World War II era.

As Kennedy moved from Kansas City to New York City during World War II, Randolph takes us through her travails both as a law school student at Columbia University and later as a lawyer. Her struggles with white law professors who were unwilling or unable to hear the logic in a black woman’s arguments about race and justice were a harbinger of the neglect and abandonment that she would encounter once she became a practicing lawyer. Indeed, the white law partners and associates that she worked with in the years following her education either ran out on her after cleaning out their firm’s coffers (leaving her with debtors that she had to settle-up with) or they left her in the middle of cases and forced her to bear the burdens of facing media, dealing with publishers, and contacting heirs alone. As Randolph makes clear, it was during this phase of her life that Kennedy began to understand that maintaining freedom as a black woman- freedom from sexism, freedom from racism, and freedom from debt- was a precarious endeavor that would require an enduring commitment to building a broad-based coalition of what she referred to as “antiestablishment” politics.

As Randolph’s analysis of Kennedy’s life and politics moves into the 1960s and 1970s, we see her practice coalition building between the nascent Black Power movement and Women’s Liberation organizations. This is the most remarkable part of Randolph’s study, as we begin to understand that Kennedy was not just an activist, not just a feminist leader and organizer, but also a teacher and a mentor to a generation of younger feminists. In particular, Kennedy became something of a mentor to Ti-Grace Atkinson, a white feminist who was also head of the New York Chapter of NOW in the 1960s. Randolph shows how, at Kennedy’s insistence, Atkinson began to construct a radical vision of feminist politics that was modeled in some part on the tactics of the Black Power Movement. For example, Randolph demonstrates that just as Black Power organizations tried to practice participatory democracy by allowing members to form committees without approval, oversight, or firm direction from organizational leaders, Atkinson tried to institute participatory democracy into the operation of NOW. Though the move was not popular with other leaders in NOW, and led to both Atkinson and Kennedy resigning from the organization, this did not end Atkinson’s emulation of learning from and borrowing tactics from the Black Power movement. Perhaps because Atkinson and others like her did not participate extensively in Black Power organizations, it has escaped scholars’ attention that they nevertheless built their visions of separatists, feminist politics with Black Power ideologies in mind. Randolph makes it clear, however, that it was not necessary for white women to be physically present and in attendance during the unfolding of the Black Power Movement. After all, they had access to and engagements with Flo Kennedy, and it was she rather than any black male leaders who helped women like Atkinson see the importance of Black Power.

Kennedy’s relationship to Black Power was not without conflict and debate, and, as Randolph argues, this was nowhere more clear than in debates over abortion. Kennedy challenged the Black Power position that abortion was an assault on black families and instead challenged the movement to see the prevalence of death from illegal abortion in black communities as an attempted genocide of black women. What Randolph shows by highlighting this conflict is that first and foremost practicing Black feminism was not easy, as the road to liberation seemed to require allies but was also full of unpredictable conflicts with would-be allies. Yet these debates, conflicts, and difficulties never seemed to make Kennedy question her commitment to broad-based coalition building. In contrast to the notion that successful political activism requires everyone belonging to radical movements to think similarly or close to the same about all topics under consideration, Kennedy seemed to understand that debate, false starts, and contestation of political ideas are constitutive of, and not contradictory to, coalition building. In this manner, Randolph asks us to consider that historical narratives of the 1960s and 1970s that have heretofore focused on the failures of coalition building- and specifically those narratives that have defined coalition building as a “failure” due to the presence of conflict or dissention between feminists and the Black Power Movement- have left us with a portrait of the times that leaves no room for individuals like Flo and Ti-Grace Atkinson who regarded conflicts and debates between and within groups as necessary. Only through the airing of grievances and differing opinions could one radical group learn from (or teach to) another. In other words, what Randolph demonstrates is that through the example of Flo we can see that, far from regarding conflict between organizations as a sign of failure, we must probe deeper to understand the ways that such conflicts generated borrowings, reconfigurations, and adaptations between and within liberation movements.

Randolph has thus given us a courageous book and in the process has managed to bring one more overlooked individual more squarely into our historical reconceptualization of the 1960s, of Women’s Liberation, and of Black Power. Yet as much as this is a book about Florence Kennedy, it is also a book about coalition building and the politics of pivoting between groups. It also provides us with a model for thinking about the place of open debate and contestation in the formation of radical public politics. Randolph’s study should thus not only appeal to scholars of black feminism or Black Power, but also to anyone interested in the relationship between black political practice and theories of the public sphere.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

You should also read her book: Color Me Flo. I met her, and she was awesome.