Between Europe and the Black Atlantic

*This post is part of our new blog series on Black Europe. This series, edited by Kira Thurman and Anne-Marie Angelo, explores what it means to bring the category of Black Europe to the foreground of scholarship on Europe and the Black Atlantic.

June 2018 marked the seventieth anniversary of the voyage of the former troopship Empire Windrush, arriving at Essex’s Tilbury Docks with over 1000 passengers, including over 500 Jamaicans. Their arrival in 1948 has come to stand for a new phase in the history of Britain, and there remains a widely-held perception within political and popular audiences that ‘multi-cultural’ Britain began with this coming of Caribbean people after World War II. The months leading up to the anniversary have been marred by what has become known as “the Windrush Scandal;” the realization, reported initially in the mainstream media by The Guardian, that Caribbean people who formed part of the Windrush generation were being detained, deported, and denied access to vital services such as health care because of an increasingly “hostile environment” that sought to target individuals by requiring impractical levels of documentation to prove they had the right to live in Britain, whether they were British citizens or not. Though the brutality of the policy has most forcefully fallen upon the shoulders of elders from the Black British Caribbean community, it is a potential threat to the security of all former Commonwealth citizens whose status as colonial subjects and British citizens has been made and unmade by successive British governments legislating the changing face of empire.

It is empire that so closely links the Black histories of Europe: exploration and exploitation; global economic networks; the trans-Atlantic slave trade and plantation slavery and the parallel presence of Black people in Europe as enslaved workers, servants, colonial laborers, political and anti-racist activists, parents, children, brothers, sisters, neighbors, and, eventually, citizens in Europe and European citizens. It is a history that is long, complex, and still relatively little understood. The work of African American historians and cultural theorists has played an important role in the development of Black historical research in Britain, but one key historical and theoretical connection between Black Europeans is the history of European Empires. This is a legacy that makes Black British history a part of the Black Atlantic and of Europe. Yet, these interconnected histories are still easily ignored in the “island stories” the British retell themselves. Partly because of this isolationist approach to British historical narratives, Black history remains marginalized in the popular imagination and academic history teaching. It is perhaps why the Windrush Scandal has come as such a shock to some, whereas others are not surprised that a nation which has had such difficulty critically addressing its racialized past finds itself treating its Black citizens with such little respect.

In 2011 the exhibition Angelo Soliman: An African in Vienna opened at the Wien Museum. It was an extraordinary story of a man who was enslaved as a child in the 1720s, sold to a Sicilian family, and became a personal attendant of Prince Lobkowitz. From 1753 Soliman lived in Vienna, tutoring the prince’s children, and later living as a private gentleman with his family in a suburb, becoming a freemason at a Lodge of which Mozart was also a member. Soliman was not a lone African in Vienna. The exhibition noted at least forty others and estimated up to 200 Africans might have lived and worked in the city at the time. They included Peter Weiß, Carl Paston, and Theresia Martin. The familiar legacy of slavery means that none of them have names that obviously identify them as Africans in the archive.

This is also the case for the descendants of the enslaved in British archives. The color of a person’s skin was not routinely (or at least officially) recorded in the archives created by the British state until the twentieth century, so baptism, marriage, and census records tend to be marked by color only because of the particular interests, curiosity, or racism of an individual administrator or official. The digitization of archives has made it possible to pick out such random references, particularly in newspaper articles and advertisements. Through these we are able to gain a sense of Black working class histories from “coloured” women seeking work as nurses and housemaids, to Black barmaids and actresses performing parts in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and Black men working as coachmen and doormen.

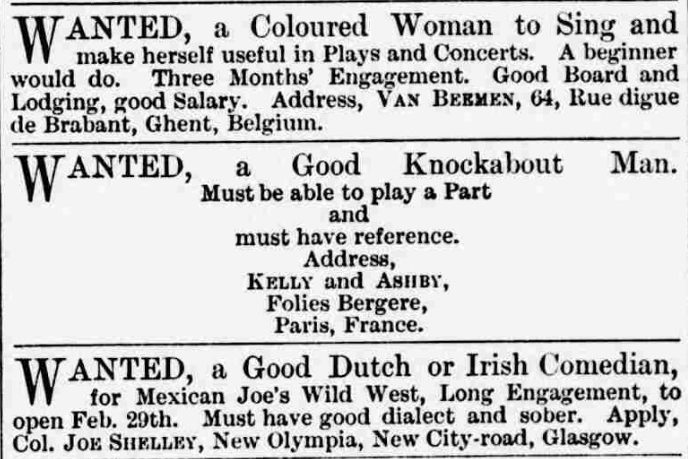

The pages of the newspapers also reveal occasions when women of color were specifically requested for jobs in Britain and across Europe. In October 1892, an advertisement was placed in The Era (a paper for those who worked on and around the stage) for a “good-looking coloured lady to travel,” further details would be sent on receipt of a photograph. For someone interested in spending time in Belgium there was an opportunity in Ghent for “a coloured woman to sing and make herself useful in plays and concerts” in 1892. The position came with board, lodging, a salary for three months, and a chance to try out a new place outside Britain, where the advertisement was placed. The following year an agency in St. Petersburg advertised in the British press for “Dancers, Lady Gymnasts, American Coloured Lady Vocalists and Dancers” for the “most brilliant Variety Establishment and Pleasure Gardens in Europe.”

These ads are just a few lines long and give the briefest glimpse of individuals, but Black people can be more easily seen in images. In my own research this has been through the sepia portraits of Victorian photographs preserved in the archives of asylums, prisons, and hospitals. Their presence is to be found far earlier thanks to the European fashion for seventeenth century aristocratic portraits to include young Black servants. A portrait of Louise de Kéroualle, painted in Paris in 1682, is held by the National Portrait Gallery, London. The rich oils depict a young Black child presenting precious coral and pearls in a shell to the French woman who became a mistress to Charles II. The portrait is a reminder of how Blackness has been used to elevate white privilege across Europe, and how little regard has been given to Black people for this forced labor. The portrait is still officially known as Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth; no mention is made of the Black child who plays such an important supporting role. The refusal to accept Black people as present, as an essential part of the picture, even when they can clearly be seen means, sadly, it cannot be surprising that the Windrush generation finds themselves treated so disgracefully.

Of course, Black people do not always play a supporting role in portraits. At the National Gallery in London, Edgar Degas’s portrait, Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando hangs in Room 42. In 1879, LaLa, also known as the “African Princess,” performed in Manchester and in London at the Westminster Aquarium, displaying her skills as a strongwoman, wire walker and trapeze artist. She also performed in Paris at the Cirque Fernando and it was here that she was captured by Degas. LaLa was born in Stettin (then in Prussia now in Poland) in 1858 and was a popular performer in Europe. The circus is one example of how Black individuals moved and worked across Europe long before the European Union’s principal of a free movement of people. John M Turner’s work on Black circus performers has uncovered Joseph Hiller, “reputedly Black or a mulatto,” who toured Britain between 1829 and 1842, and set up his own company which went to the Cirque de Champs-Elysees, Paris in 1844. His daughter, Grace Hillerm, became a horse rider though she is believed to have remained in Paris unlike Miss LaLa, who is thought to have moved to the United States. George Christoff, a tight rope performer and vaulter, was the son of Christopher, a Black man who was “one of the finest rope dancers of the world.” Christoff ran his own company in Birmingham in 1856, but his son performed in Lisbon and Moscow. Being known as the “African Princess” did not seem to shape LaLa’s role within the circus, but others such as lion tamers were racialized, at least by British companies touring around Europe. In March 1883, Powell and Clarke’s circus advertised in The Era for a “coloured man or woman, to perform with the serpents” in Ireland. And in September 1900 Bostock and Wombwell’s Menagerie used The Era to advertise for an animal trainer. Based in the north of France, the successful candidate would have their passage paid for from London. They did not have to be Black, but the company hoped to hear from Davis a “Coloured Man.”

There is a need for British Black history to connect more closely to European histories in order to better understand the similarities and differences that the legacies of European Empires, the World Wars and the building of the European Project have had on Black people across Europe. How such research might be undertaken in a post-Brexit Britain is uncertain. The role played by racism during the Referendum campaign continues to be debated. For many, the arguments of Leave voters highlighted an imperial nostalgia or melancholia that had long been criticized by critical race theorists such as Stuart Hall and Paul Gilroy. The fate of those caught up in the Windrush Scandal reflects the individual damage a failure to face the complex histories of empire has caused in Britain. To some extent this is exemplified through the memorialization of the Empire Windrush. Though the presence of Jamaicans and other Caribbean people on the ship is commemorated and sometimes even celebrated, that there was also a small group of Polish refugees and over 100 people who gave England as their former place of residence on board is rarely mentioned. These intertwined histories of travel, migration, war, displacement, and empire closely link the histories of Europe, but so do the histories of the everyday, of going to the circus, of finding work and living together. The histories of Black people in Britain have not emerged in parallel to histories of Britain; they are the histories of Britain, from its place on the global stage to the very local stories of streets and neighborhoods. A failure to include Black people in these histories is a failure to examine British history in its fullest sense. Such histories may be unsettling and challenging for some, but they are also vital if the pain caused by the Windrush Scandal is not to be repeated.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

This is a very insightful article, especially the point made on blackness and the archives. Thank you!